[page 236]

Appendix 1 to Annex F: Responses to the Call for Evidence

Responses from organisations

16 Plus Heal Louise

19+ Action Group Judge Paul

19+ special needs Patterson Judith

A Cause for Concern Levell Peter

Accrington & Rossendale College Harford Lindsay

ACE/Access Centre Broadbent Steven

Acorn FE Centre at Rampton Hospital Oxley Rachel

Acquired Aphasia Unit Cooper Jayne

Action For ME Colby Jane

Adult Basic Education Service Dartnell Vivienne

Adult Dyslexic Organisation Soloman Ruth

Adult Vocational and Educational Support Services White Paul

Airedale and Wharfedale college Greenwood N D

Albert Place Centre & Meadowside Centre, Trafford Social Services

Adult Literacy and Basic Skills Unit Wells Alan

Alton College Rumble Michael

Amersham & Wycombe College, FE Corporation Leman Patricia

Aquinas College Moore Eddie

Arnold and Carlton College

Arts Council of England (The) Semple Maggie

Ashworth Adult Education Department Thomas R

Assets Disability Carter Ken

Association for Colleges Brookes David

Association for Residential Care Churchill James

Association for Stammerers Cartwright Peter

Association of Camphill Communities of Great Britain Luxford Michael

Association of Colleges in the Eastern Region Young Andrew

Association of County Councils Campbell Stephen

Association of Educational Psychologists Harrison Joyce

Association of National Specialist Colleges, The McGinty Jean

Association of Workers for Children with Emotional and

Behavioural Difficulties Rimmer Alan

ATLA Chalmers Roz, Hunter Penelope, Mitchinson Freda, Newton H, Poole Christina

[page 237]

ATLA Rallings Philippa, Smith June, Uren Jackie, Zysblat J, Plail Gillian, Gamage Mr and Mrs (students), Hatton Joan (student), Love Elsie (student), McDouall Kenneth (student), McDouall Joan (student), Parker Joyce V

Avalon Trust Phillips Helen

Avon Coalition of Disabled People Pickersgill Ruth

Avon Community Education Allan Yvonne

Avon County Council Crook Maggy

Award Scheme Development and Accreditation Network (ASDAN) Harper Steve, Swaffield Karen

Aylesbury College Lawson Don

Aylesbury Society for Mentally Handicapped Children and Adults Richardson K

Aylesbury Vale Community Healthcare NHS Trust Kuzmanov Cilla

Barking College Brunyee David

Barking and Dagenham LEA Hillsden S

Barnados/Cheshire Social Services Thornton Mair, Howe John

Barnados/lan Tetley F. E. P. Pickup Chris

Barnet College Crennell Margaret

Barnsley College Pickett Norman G

Basic Skills/Learning (Drop in Centre) Gray Terence, Martin Frank

Basildon College Woodrow S J

Basingstoke College of Technology Bird Kay, Parker J

Beckton School Angele Maggie

Bede College Wakefield I M

Bedford College Reece D J

Bedford College Learning Support Team

Bedford Spastic Society Residential Centre, The Cunningham John

Bedfordshire County Council Alexander C A

Bedfordshire Guidance Services Alexander C A

Bedfordshire Society Working with Autism Jones David

Berkshire Social Services Valdez Maureen

Berkshire Working Group on Deafness in Post-16 Education and Training Carter Ken

Beverley College Tuckey Sue, Anstess John

Bicester Adult Continuing Education Centre Hutchins Laura

Bilston Community College Self-advocacy Group

Birkdale Further Education Direct Support (BFEDS) Loxham E

[page 238]

Birkenhead Sixth Form College Tomlinson Barbara

Birmingham Adult Dyslexic Self Help Group

Birmingham City Council Edwards Gwenn

Birmingham College of Food, Tourism and Creative Studies Davies Clive

Birmingham TEC Giles Elaine

Bishop Burton College Davies A J

Blackburn College Ewing Sheena M

Blackpool and the Fylde College McAllister Michael J

Blenheim Centre, Continuing Education, Leeds City Council Aveyard Margaret, Wallis Margaret, Frankland Anthony

BMS, Bexley College Elgar Carolyn

Bolton Bury TEC Bain Sue

Bolton College Wilson Jean

Bolton Community Education Service Foster Liz

Bolton Institute Clift-Harris Jenny, Whittaker J

Boston College Simpsoni Adams

Bourne Social Education Centre Maclachlan Gail

Bournemouth and Poole College of FE, The Roger Simons

Scott Alison

Bournville College of Further Education MacHattie Carrie L, Burton Paula L

Boys and Girls Welfare Society Liston Judy

Bracknell College Marston Dianne

Bradford Eduction Advice Centre Sutcliffe Godfrey

Bradford & Ilkley Community College Chambers Peter, Donkin Joan, Neal Les, O'Connor Lynette

Braintree College Greenard S L

Breakspeare SLD School, parents' group Topping Janet

Breakthrough Deaf-Hearing Integration Jarrett Dawn L

Bridge College Preece Sue, Ridgeway Andrea

Bridgeway Centre, The Cronin Gaynor

Brighton College of Technology Brownhill M

Brighton, Hove & Sussex Sixth Form College Blyth Margaret

British Association of Teachers of'the Deaf Shaw John F, Underwood Ann

British Dyslexia Association Cann Paul

British Epilepsy Association Harnor Mike

Broadview Further Education Centre Walker Angela

Brockenhurst College Snell M J

Bromley Health Edmonds Janet

Brooklands College Copas P J

Brooksby College Clohesy John Mark

Broomfield College Wilkinson Anne

Broxtowe College Lewis I N

[page 239]

Brunel College of Arts and Technology Bevan W I

Buckinghamshire Adult Continuing Education Scott Peter

Buckinghamshire Social Services Young Stan

Bury Health Care NHS Trust Bacon P

Bury People First Pearce Sharon

Bury Resource Centre Williams Deborah, Delves Ian, Coatham Lynn, Wakeling Ian

Business and Technology Education Council Billam Diane

Calderdale College Sunderland Val

Calderdale Healthcare NHS Trust Ellis Linda

Cambridge City Council Cracknell Tim

Cambridge Regional College Coulthard Margaret

Cambridge and Huntingdon Health Commission Williams Stephen

Cambridgeshire County Council Forbes Martin

Camden and Islington Health Authority Tinsley Peter J

Camphill Blair Drummond Bruhn Michael

Canterbury College Manser Edward

Capel Manor Horticultural and Environmental Centre Adams C R

Capers (Starbright Group) Falkingham Beryl, Pencavel Marian

Careers Service West, Bristol Fryer Ian

Carers National Association, Newham Branch Watts Mary

Carlisle College Johnson Andrew

Carmel College Conwell Kathy

Carshalton College Watkins David

Castlebeck Care (Teesdale) Ltd Betton Michelle

Cathedral Centre Haskins Mary, Topham Richard

Catholic Caring Services Bolton Donna, Clarkson John, Jordan Susan, Sadiq Faryaz

CAVE O'Malley John

CELFACS Community Learning Disabilities Team Ackroyd Carol

CENMAC Tingle Myra, Becke Gil

CENTRA (FE Cenh-e of NW Regional Association of LEAs) Young Barbara H

Central Middlesex Spastics Society Skills Development Centre Harrison Marie

Chadsworth School Main M W

Charles Keene College Gray Linda

Chelmsford College Walden Phil

Cheshire Careers Service Smith Jean

Cheshire County Council Donnely Verity

Cheshire Merseyside & West Lancashire District Workers'

Educational Association Hall Dorothea

Chesterfield College Spilman Liz

Chichester College of Arts, Science & Technology Fairbank Sandie

[page 240]

'Choices' Work Placement Programme Buckley Eileen, Rogers Avril

City and Guilds of London Institute Butcher Murray

City and Islington College McLoughlin Frank

City College Manchester Farrell Sheila

City College Norwich Debbell Diane, Brannen Richard

City College Norwich Turner Richard

City Lit Support Unit, The Morton Denise

City Literary Institute, The Cooper-Hammond John, Davey C, Fearnley Clare, McKenna Stewart

City of Bath College Clayton Brenda

City of Leeds College of Music Equal Opportunities Officer

City of Liverpool Community College Malach Alyson

City of Liverpool Education Directorate Roberts Ken

City of Salford Social Services Department Hewitt Peter

City of Westminster College Leavy I (and students), Miles Carol, Woollacombe Nick

Clarendon House Ives Cheryl Margaret

Cleveland County Council, Adult Education Service Kenrick Julie

Cleveland Social Services Department Lauerman M

Coalition of Advocacy Groups (Sheffield), The Naylor Graham

Colcheser Institute Winder Enid

Coleg Elidyr Parents' Association Cowie Noeline

College of North East London Harries Waveney, Prince E, Self-advocacy Group LDD section, Robinson Ian

College of North West London, The Smith Reg

College of Occupational Therapists Hall Michael

Community and Social Services Department, Wakefield Raynor Mervyn

Community Team for people with learning difficulties, Wiltshire Simpson Helen

Community Team for people with learning disabilitites, Bucks Hatfield Christine

Computer Centre for People with Disabilities/National Federation of Access Centres Laycock David

Connect Peggs S E

Cornwall College Allsop Trish, Stanhope Alan

Cornwall County Audiology Service Dwight D W

Cornwall Deaf Childrens Society Sweet Elaine

Cornwell Business College Cornwell J

Council for Disabled Children Russell Philippa

Council for the Advancement of Communication with Deaf People Simpson T Stewart

Countersthorpe College Centre 88

County Transition Advisory Group, Lancashire Howarth I R

[page 241]

Coventry City Council Community Education - N W Area Selby Ann

Coventry Education Department Galliers D

Coventry Social Services Department Summerfield Jenny

Coventry Technical College Eastman Jessica, Lee Ann

Craven College Walton Jennifer

Crawley Hard of Hearing Club Annells Sheila

Cricklade College Bevan Eva Mavis, Browning Peter

Croydon College Brett Terry

Cumbria Careers Ltd Ludlow Peggy

Cumbria Deaf Association Verney Ann

Cumbria LEA Slater Harry

C.D.T. Line Angel Stella

Darlington College of Technology Hollis George

Denbigh Education Centre Wilson Lesley

Department of Health Cooper E D

Derby College Ashman Susan

Derby College for Deaf People Iqbal A

Derbyshire Careers Services Miln Beverley

Derbyshire County Council Community Education Service Rae Donald

Derbyshire County Council Adair Lin

Derwentside College Menzies Bos

Devon Careers, Exeter Moran Cathy

Devon Careers, Plymouth Fortey John

Devon County Council- Education Department Jenkin S W G

Dewsbury College Coleman Margaret

Dilston College of Further Education

Disability West Midlands McCorkindale Susan

Disabled Living Foundation Bennett Susan

Doncaster Careers Service Kime M A

Doncaster College Calloway Neil

Doncaster College for the Deaf Dickson R B, Evans I B D, Emmott T K

Dorset Social Services Department Kippax Chris

Down's Syndrome Association Campbell Bridget

Doyle Centre (Devon County Council) Folland M M

Dudley College Roper S C

Dundee Careers Service, Special Needs Advisory Group Grant John

Dyslexia Institute, The Brooks E I McCormack Eileen, Patterson Felicity, White S

Ealing Tertiary College Nind M N

East Berkshire College Berisford S

East Berkshire Community Health Smith Karen

East Berkshire NBS Trust - Gilbert Jan

East Birmingham College Harper Stephanie

[page 242]

East Devon College Lucas Alison

East Gloucestershire NHS Trust Fretwell B

East London & City Health Authority West Sylvia

East Midlands Further Education Council (EMFEC) Ainscough Roy

East Surrey College Dunlop Bob

East Sussex Careers Services Davey Barbara

East Sussex County Council Penney Trish

East Sussex County Council Social Services Anstey M

East Warwickshire College Collins Elizabeth, Pawsey Tracy

East Yorkshire College principal

Eastbourne College of Arts and Technology Williams John A

Eastleigh College Higgins Marlene, Preston Jo, Roberts A

ECSTRA (support service for deaf people in further education) Tansell Peter

Education Department, Hertfordshire County Council Roberts Mark

Elizabeth Fitzroy Homes Eastwood J

Elms School Bacon I M

Emscote Centre Emscote Users Council

Enfield College Holm Barbara

ENTERnet Blair Sue

Epsom Hard of Hearing Group Birtwell Betty

Essex Careers and Business Partnership McMellon Bill

Evesham College of Further Education Powell Heather, Blades David

Exeter College Barnard Pam

Fairdeal Bodsworth Jo

Fairfield Opportunity Farm Hester B A K

Farnborough College of Technology Hasted Ron

FE College Holloway Jeanne

Further Education Unit (evidence subsequently published by FEU) Stanton Geoff

Filton College Coles Jonathon

First Community Health Thomas C

Firth Park Advice Centre Morris Pauline

Former Librarian Royal National College for the Blind Greenall Elizabeth C E

Fortune Centre of Riding Therapy Johnson L

Foxfield School Richardson Robert

Franklin College Parratt E

Frimley Special Courses (MEN CAP} Wright Marilyn

Furness College Plant Fay

Gabalfa Community Workshop Shiers Barry

Gateshead College Bell Susan

Gateway Sixth Form College Challacombe M S

Gillingham Adult Education Centre Hargrave Roberta

Gloucestershire College of Arts & Technology Escolme Richard

Gloucestershire County Council, Education Department Haworth D J

Gloucestershire Social Services Friar Jeremy

Grantham College Design for living course

[page 243]

Grantham College New directives course, Saville MD

Greater London Association of Disabled People Hasler Frances

Greenhead College Conway Kevin

Greenhill College Acilman Brian

Greenwich Learning Disability Services Sandean Danny

Grimsby College Lowden Celia

Guildford College of Further and Higher Education Leggett Joe

Hayes Jean

Hackney Social Services McMahon Margaret

Halesowen College Couless Michael, Couless Susan, Godfrey Andrea, Huynh Phan Tuyet, Langford Faye, Smith Mark James, Stockton Rebecca Louise, Swansborough Steven John

Hammersmith & West London College Flatley Christine

Hard of Hearing Club (Camborne) Ripsher A J, Hipsher M

Haringey Association for Independent Living Mann Polly

Haringey Housing & Social Services Keston Centre

Harrogate College Clarke Ian

Hartpury College Brookham John

Havering College of Further & Higher Education Morgan Penny

Haywards Heath Sixth Form College Derbyshire Brian

Health & Disability Team Dorchester Social Services Whitfield Ann, Jackson Shirley

Hearing Impaired Service, Humberside County Council Garnett Michael, Underwood Ann

Hearing Impaired Service, Knutsford, Cheshire Wilson William

Heltwate Special School Smith D R

Hendon College Kiestos Thomas, Leigh Ben, Miller Michelle, Patel Sheila, Phillips Steven, Runswick Elaine, Watson Stuart, John Scott

Henley College, The Kimbell M D

Hereford and Worcester Careers Service Little Roger

Hereford & Worcester County Council O'Toole Anne

Herefordshire College of Technology Purser Chrissie

Herefordshire College of Art & Design MacIntre Louise

Hereward College of Further Education Firminger Janice

Hertford Regional College Slaney Ann

[page 244]

Hertfordshire Careers Service Palmer Margaret

Hertfordshire County Council Green Colin

Hertfordshire Transition Support Group Palmer Margaret

Hertfordshire Social Care (Day Services, North Hertfordshire) Parker Bob, Gates Jan

High Peak College Martin Nicola

Highbury College Winter B

Hills Road Sixth Form College Greenhalgh Colin

Holy Cross Sixth Form College Mafi Helena C

Home Farm Trust Madden Philip, Gadd Michael

Hopwood Hall College

Horizon House Day Centre (Rugby MIND) Amos H, Geehan J, Herbert Margaret Rose, Kempton Philip, Robson P, Taylor Susan, centre co-ordinators

Horizon House Day Centre, East Warwickshire College Baldwin Iris

Horizon NHS Trust Sherratt David

Huddersfield New College Morris Ruth

Woodrow Christine

Huddersfield NBS Trust Lambert EM

Hull College Eastwood A (parent), Holian Thelma, Kettener Alan (student), White Derek (student), Andrew Phillip (student), Bentley Susan (student), Waldon Joanne, Wheatley Barrie, Wragg T, visually-impaired students

Humberside Adult Education Service, Boothferry/Scunthorpe Area Garner Susan, Cole Margaret

Humberside Education Services Thomas Trevor

Humberside Hearing Impaired Service Wolsey Lesley

Huntingdonshire Regional College Elias K

Ian Tetley Memorial School Cairns Paul

Initiative on Communication Aids for Children (ICAC) Bernadt Ann

Institute of Careers Guidance Bereznicki C

Institute of Educational Technology Vincent Tom

Integrate Ltd Trustam Rosemary

Isle of Wight College Burgess Sue

Islington Careers Service Davis S J

Islington Council Davis Steve

Itchen College Savage N

Jack Drum Arts and Entertainment Ward Julie

[page 245]

John Procter Education & Training Procter John

John Ruskin College Kennedy Mandy

Joint Group (physical and sensory handicap), Wakefield Turner David

Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Josiah Mason College Greenhough M M

Keighley College Packham Graham

Kensington & Chelsea College Howard Ursula

Kent Adult Education Service Jenkins Angela

Kent County Council, Physical and Sensory Service Rousseau Lindsey

King Edward VI College Cotton Ann Josephine

King George V College Collier P

Kingsway College Maudslay Liz

Kirby College of Further Education Smith Margaret

Kirkley Hall College Pike C J

Knowsley Community College Lane Susan, Walker Linda

Lackham College Sumner Hazel

Lambeth Accord Green Wanda

Lambeth College Milbourne Linda

Lancashire Adult Education Service Hooper R C

Lancashire County Council Carter Philip A, Rowbottom Don

Lancashire LEA Howarth I R

Lancaster University Preece J

Lancaster & Morecambe College Piggott J

Lancasterian School Rashid Shazia

Language & Literacy Unit, Southwark College Klein Cynthia

LEAP in Teesdale ABE Lee Jenny

Learning Disability Team, Exeter Hodgson Ray

LEE Services (Heritage Care) Gutman Toni

Leeds College of Technology Piercy David

Leek College of Further Education and School of Art Smith Val

Leicester South Fields College Khanna Neelam, Rayfield Susan

Leicestershire LEA Swan Julia

Leonard Cheshire Foundation/Adult Basic Education Fiddes Susan

Lewes Tertiary College Hayes Barbara

Lewisham College Holman Judy, Swabey Alison, Silver Ruth

Lewisham Community Team for Adults with Learning Disabilities Bradshaw J, O'Connor S

Library Association, The Clayton Carl, Fraser Veronica

Lifespan Healthcare NHS Trust Mackenzie Graham

Lincoln College Rux-Burton John

Link into Learning/Wigston College Chappell Doreen

Linkage Community Trust Berry Chris

Local Education Authority's Forum for the Education of Adults

[page 246]

(LEAFEA) Tuckett Alan

London Borough of Croydon Social Services Department Lyons Sharon

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Education Department Dickinson Phil

London Borough of Sutton, Housing & Social Services McIntosh Barbara

London Borough of Waltham Forest Crowley Mary

London Chamber of Commerce and Industry Examinations Board Lysons Kenneth

London Learning Disability Forum Cox Brian E

London Region TVEI Network Dee Lesley, Hill Mary, Maudslay Liz

Long Road Sixth Form College Robinson Peter

Longlands College Dyce Tom

Loughborough College of Art & Design Bunkum Alan

Ludlow College Pafford David

Luton Sixth Form College Bennett Sue

Macclesfield College Summers Judith

Macintyre Care Lock Chris

Mackworth College, Derby Pickering Malcolm

Making Space Lyne David

Manchester Adult Education Service Corbridge R L, Chadwick Janet

Manchester College of Arts and Technology Kirby Pat

Margaret Danyers College Parker Margaret A

Marshfields School Berryman B

Matthew Boulton College, Student Forum Mason Lynn

Meadowside Centre Advocacy Group

Meanwood Park Hospital Beckett Claire, Buchan Terry

Meldreth Manor School The Spastics Society

MENCAP Heddell Fred

MENCAP, District Office, Berkshire/Buckinghamshire/Oxfordshire Tan Elizabeth

MENCAP, Northern Division Parkin John

MENCAP, Pathway Employment Service, Rotherham Bostwick Fiona

MENCAP, E/I Support Group Edington O M

MENCAP, Amersham and Cheshire Horrex K Elizabeth

MENCAP, Bedford Scargill Veronica

MENCAP, Bristol Hannam Pam

MENCAP, Dunstable Mercier Wendy

MENCAP, High Wycombe Billington J, Sterry Molly

MENCAP, Maidenhead Johnson Jean H

MENCAP, New Forest Pepper Sue

MENCAP, Nottingham Bramhall Debra

MENCAP, Southampton Labon Kay

Meridans Student Council, Resource and Activity Centre Petrie Moira

Merton Sixth Form College Fairless Hilary Fairweather J

Merton Sixth Form College Lake Ruth, Jackson Joann

[page 247]

Metropolitan Borough of Stockport Cross Arthur

Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Local Education Authority Griffiths David

Mid-Cheshire College Ellingham R

Mid-Staffordshire Health Authority Sorual Imad

Mid Warwickshire College Critchley H

Middlesex LEA, Psychology Service Phillips P

Millfields S.E.C. (social services) Robinson John

Milton Keynes College Bedlington Jane

Jarvis Linda

Molly Cope Court Cope Richard

Monks Park School Dent Alan William

Monkwearmouth College Upright Richard

Morley College Craven Judy, Van de Water Mary Ellen 1993, Student Executive Committee

Morningside Further Education Centre Taylor Eric, Holmes Linda

Myerscough College Morwood Alistair W

National Association for Tertiary Education for Deaf People (NATED) Mullen Brenda

NATFHE, the University & College Lecturers Union Taubman Daniel

National Association for Special Educational Needs, The Hawkins Jean

National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders Hraboweckyj Anna

National Association of Principal Educational Psychologists O'Hara Min

National Association of Teachers of English & Community

Languages To Adults Siudek Margaret

National Autistic Society Collins Michael

National Deaf Childrens Society Laurenzi Carlo

National Development Team Platts Helen

National Extension College daSalvo Anna Pinchbeck Amanda

National Federation of Access Centres Firminger Janice, West Bob, Williams Rees, Goodacre John

National Mencap Homes Foundation Baker Colin

National Schizophrenia Fellowship Took Mike

National Youth Agency Hand Jenny

National Association for the Education and Guidance of Offenders

NCT Parent Ability, The National Childbirth Trust O'Farrell Jo

NEDRDA Hill Sue

Nelson & Colne College Gilchrist Helen

New College, Durham Harrison Barbara

NEW College, Pontefract Machin David

New Tunmarsh Centre Mistry Rajendrakumar

Newark & Sherwood College Towner Peter

Newbury College Bickell Kerrie, Worsley Enid

[page 248]

Newcastle-Under-Lyme College Ayres R F, Granter J

Newcastle College Bagshaw John, Farquharson Lynne

Newcastle Education Department Flynn Pam

Newcastle Further Education (NCFE) Sutcliffe Isabel M

Newcastle & District Hard of Hearing Club Harrison S C

Newham College of Further Education Davies Rachel

Newham Council, Social Services Department Constable Gill

Newham Learning Support Service Lowe Mary

Newham Parent's Support Network Goodey Christopher

Newham Sixth Form College

National Institute for Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) (evidence subsequently published by NIACE) Tuckett Alan

Norfolk Adult Education Service, lip-reading tutor Peck Doris

Norfolk Careers Service Holt Tim

Norfolk College Dockney B C, Porter S M

Norfolk County Council, Careers Service Wedsell Colin

Norfolk County Council Education Godding Bernard

Norfolk Network 81 Brickley Pat

North Birmingham College Eyre J

North Cumbria Health Authority Macleod R A

North Derbyshire Tertiary College Kavanagh-Coyne J

North East Worcestershire College Gamble Jon, Welsher Linda M

North Hertfordshire College Armstrong Eileen

North Hertfordshire People First Hitchin Group

North Lincolnshire College Plunkett Barbara

North London TEC Wood Simon

North Trafford College Robinson T

North Warwickshire College Jones Stephanie

North Warwickshire NHS Trust Moulin Lawrence

North Yorkshire LEA Allgood G B

North Yorkshire Careers Guidance Services Ltd Robinson Jacky

North Yorkshire County Council, Learning Opportunities Goring Anne

North Yorkshire County Cowlcil, Social Services Department Rhodes Cynthia M

North Yorkshire Health Authority Griffin Leigh

Northampton College Hays Catherine, Quilter Ruth

Northamptonshire Adult Education Service Dodds C R

Northamptonshire County Council Goulding Kerstin

Northamptonshire Further Education Group for Students with

Disabilities & Learning Difficulties Matthews Graham

Northamptonshire Social Services Department Hugman Ian, Pounder Tony

Northbrook College Reglar Peter

Northgate Further Education (NHS Trust) Bewick Janet M

Northgate Hospital, Further Education Department

Northumberland College of Arts & Technology

[page 249]

Northumberland Training & Enterprise Council Ltd Cook Maureen

Norton Radstock College Salter T S

Norwich Road Community Resource Vanhinsburgh Julie

Nottingham Community Health, NHS Trust McGuirk Elizabeth

NSF Ives Christopher

Nuneaton Adult Team, Social Services Department Smith S

Nuneaton Social Education Centre

NWA healthcare Hughes G

N.M.C. (Neuromuscular Centre) Kelly Sarah

Oak Lodge School East Anne

Oaklands Centre, The Glenn M J

Oaklands College Nelson Steven, Woods Rosemary, Learning Difficulties Co-ordination Group

Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) Chorley D H

Office of Public Management Brown Helen

Oldham College McHugh Wendy

Oldham LEA Edwards Kathleen

Oldham NHS Trust Ryan John, Steward John

Open University, The Peters G, Walmsley J

Opportunities and Networks in Southwark Dunn Susan, Honess Julia

Optimum Health Service Auty Patricia M

Orchard Trust, The Gordan-Smith George

Oxford Brookes University, School of Education Bines Hazel

Oxford College of Fmther Education Otley Noel

Oxfordshire County Council Brayton Howard

Pace Enterprise and Employment Services Bottomley John

Parents and Carers Group, WALCAT Cornell Angela

Park Lane College Brown Jonathon

Paston Sixth Form College Downes Barbara

Peggy Edwards Centre Richards Rowena

Penn Fields School Hodgson R

Pennine Carnphill Community, parents of students Gosling I B

Peter Symonds College Samways Angela

Peterborough Regional College Fisk Stephen

Peterborough Regional College Stapleford Keith

Peterlee College Goodrum Val

PHAB Hope Paul

Phoenix NHS Trust Le-Pine Lesley

Phillips Resource Centre Weare Lynda

Plymouth College of Art & Design Farrow-Jones Sue

Plymouth College of Further Education Rospigliosi G, Baxter Marion, Lloyd Barry, Lile Sheila

[page 250]

Plymouth College of Further Education skills development programme, Stone Vivienne E, Stutridge Marianne

PMLD Link, Editorial Board Boucher Joan

Portland College Davies P S

Portsmouth College Westbury Richard

Portsmouth & Havant Post-16 Forum Baker John, Foster Andrew

Priory School Mummery Frances

Prison Education Consultant West Tessa

Queen Elizabeth Sixth Form College Woods Peter

RETC Fidler Lynda Mary, Hayes Jane

Rathbone Society, The Gould Alison

Ravenswood Hart David, Brier Norma

Reading Adult College Westbrook Joan

Redbridge College McGrath I A

Redbridge Health Care Kelly Alex, Rosen Alison

Reigate College Walters Sarah

Richard Collyer in Horsham, The College of Clarke Paul

Richard Huish College Stokes Barbara

Richmond Adult & Community College Evans Mary

Richmond upon Thames College Vallance Jenny

Ridge College, The Lyon Ann

RNIB Redhill College Stockley Jennifer

RNID Court Grange College Whitehead Graham

Romsey and Waterside Locality Planning Teams Adult

Education Subgroup Evans Anne

Rose Cottage Further Education Unit (Glyne Gap School) Baker Steve

Rotherham College of Arts & Technology Sheehy Sue

Rotherham Further Education Partnership on students with

learning difficulties and disabilities Richards Colin

Rotherham Social Services Department Chester David

Royal Association for Disability & Rehabilitation, The Simpson Paul

Royal College for the Blind, The Housby-Smith C

Royal College of Nursing Hancock Christine, Sines David

Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust Voyce M A

Royal Hospital NHS Trust, The Francis Dennis

Royal London Society for the Blind, The Spittle Barbara

Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) Dryden G

Royal National Institute for the Deaf (RNID) Alker Doug, Gaines Adam

Royal School for the Deaf Hedges Joyce

Royal School for the Deaf Shaw John F

Runshaw College Wales Janet

Rutland Sixth Form College Firmin Catherine

[page 251]

Salford Careers Service Loader Kay

Saltash College (part of St Austell College) Wright Malcolm

Salvation Army Social Services Robinson John

Sandwell Strategic Forum for Education and Training, The Holding Gordon

School Leaver Liaison Group, SRT, Stockport Whiteley Viv

SCSI-ASSIST York Debra, Perry B T

South East Derbyshire College, Ilkeston Jones Judith

South East Regional Association for the Deaf Holt S John

South East Regional Group of Special Needs Careers Officers Glover Sharon, Higgins Gillian

Second Chance, Bridgenorth College Campus Cooper Lynn

Second Chance, Shrewsbury College of Art & Technology Fricker Angela, Matthews Pam

SENSE: The National Deaf Blind and Rubella Association Boothroyd Eileen

Sensory Impairment Service, Oxfordshire Moore Edward

Service for Visually Impaired Children, Coventry Wright R A

Shaftesbury Education Burnham Michael

Sharing Care, Leeds Walton Bill

Sheffield College, The Lynch Paul R, Martin Christine

Sheffield Family & Community Services Jones Glenys

Shelley School Parker Heather, Thomas Jillian P

Shena Simon College Young Glyn

Shrewbury College of Arts & Technology Conrad Patrick, Rudd Chris

Shrewsbury Sixth Form College Francis Sally

Shropshire Social Services Painter Roger

Sidestep Training Ltd Laycock Deborah

SIMS Education Services Carr-Archer H

Sixth Form College, Farnborough, The Harris Marilyn

Skelmersdale College Farmer Ian

Skill, Mental Health Working Party Chirico Margaret

Skill (Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Group)!Yorkshire and Swindells David

Humberside Association for Further and Higher Education Hills Graham

Skill (North West) Region Johnstone David

Skill: National Bureau for Students with Disabilities (evidence subsequently published by Skill) Cooper Deborah

Skill (Yorkshire and Humberside Branch) Swindells David

Slough Family & Child Guidance Service Brockless J

Social services, Northallerton, North Yorkshire Pudney Juliet

Social Services, Bedfordshire O'Sullivan J

Social Services, Hertford Woolrych Richard

Social Services Adults with Learning Difficulties, South Wirral Jones Harry

Social Services Department, Lowestoft, Suffolk Gibbons Sheila

Social Services Department, Bury St Edmonds, Suffolk Goodenough Teresa

Social Services Department, Cheshire County Council Sargeant Helen

Social Services Department, Wolverhampton Gray Ken

[page 252]

Social Services, Walsall Phillips Don

Social Sevices Dunkerley Dinah

Solihull Careers Service Taylor D E

Solihull College Lowe Vicky

Somerset College of Arts & Technology Davies Bryn

Somerset College of Arts & Technology Lloyd-Jones Nicole, Tacageni Christopher

Somerset County Council Mayor George

Somerset County Council, Learning Difficulties Strategic Barwood Ann

Planning Team Harvey David

Somerset Social Services Singleton Sue, Bale Fleur

South Birmingham College Cooper Maureen

South Bolton Sixth Form College

South Bristol College Taylor Prue

South Cheshire College Briscoe S C

South Devon College Lupson I F

South Downs College of Further Education May Fran

South East Derbyshire College Jones Judith

South East Essex College of Arts & Technology, The Pitcher A

South East Essex Sixth Form College Dennis L J

South East Region Special Educational Needs Network MacLeod Vicki

South Humberside LEA Hayward Anne

South Kent College Berry Christina

South Park Sixth Form College Walker Muriel

South Thames College Vigurs . Annette

South Tyneside College Piddington Pauline

South Tyneside LEA Reid I L

South West Association Further Education & Training Blythe Penni

Southampton Technical College Grenier Anne

Southampton Day Services Lillywhite Ross

Southampton Health Commission East K

Southend Community College Warnes Jill

Southgate College Dowrick Jill

Southport College Hobson Margaret

Southwark College Foster John, Held Madeleine, Rose Judith

Southwark Day Care Forum Rose Judith, Hurley Irene

Spastics Society, The (now SCOPE) Gilbert David, McGill Rosemarie

Special Adult Learning Programmes, Bedfordshire Adult and

Continuing Education Harris Meryl

Special Comunication Needs Ltd (SCN) Hugh Stefanie

Special Education Needs Training Consortium Dee Lesley

Specialised Courses Offering Purposeful Eduction (SCOPE) Adams B

Speech and Language Therapists, The College of Beer Marcia

Speech & Language Therapist for the Deaf, Royal Berks Hospital Crawford Rachel

[page 253]

Spelthorne College Lewis Anne

Springfield School Lewis D

St Ann's School

St Charles Catholic Sixth Form College O'Shea Paul

St Dominic's Sixth Form College Lipscomb John L

St Georges Healthcare (NHS) Trust Way Andrew M

St Helens College O'Brien Derek

St John Ambulance Brigade Davison Edward Richard

St John's School for the Hearing Impaired Ellis Angela

St Mary's NHS Trust Hospital Ajayi-obe Abiola

Staff College, The Toogood Pippa

Staffordshire ASSIST Garner Malcolm W

Staffordshire County Council Hunter P J

Stanmore College Wise J

Stanton Vale School Ormerod P N

Stockport College Marley Joyce

Stockport Health Authority Trust, Education, Social Services - Multi-Agency Whiteley Vivien

Stockton and Billingham College of Further Education Larry A E

Stoke-on-Trent College Bradbury Kathryn, Powell R T

Stoke-on-Trent Sixth Form College Richardson J

Stourbridge College Pugh Vivienne

Stratford Upon Avon College Sheils D P

Stroud College of Further Education Critchley Zen a

Suffolk College Serritiello Carmine Renato

Suffolk County Council Day Services, Unit 9 Business Services Service users

Suffolk County Council Community Education Service Hopkins Annie

Suffolk Social Services Department Kent Simon S

Sunderland Social Services Hepplewhite Ian, Marsden John

Surrey Adult & Continuing Education Service Jackson Irene

Surrey Hearing Impaired Service Barton Liz

Surrey Training & Enterprise Council Essex Mike

Sutton Coldfield College of Further Education Turner Gwen

Sutton College of Liberal Arts Hebden Kate

Swalcliffe Park School Trust Cooling Maw-ice

Swindon College Budd Patricia

S.C.AT. Newton Eric John

S.C.A.T/Six Acres Day Centre Veysey Ginny, Freeney Mike, Furey Michelle (student), Young Gillian (student)

Taking Part Bryant Caia

Tameside College of Technology Burgess Barbara, Luckock Ann

[page 254]

Tamworth College Boughton G, Hendy Alan

Coventry Education Service, Task Group for Developing Work with Adults with Learning Difficulties Newbold Alan

TEC National Council Muir CBE Peter J

Telford College of Arts & Technology Glazier John

Templehill Community Ltd Keys Richard

Tendring Adult Community College Garlick Cynthia, Mathieson Michael

Thanet College Morgan Cheryl

Thomas Danby College Dugan Theresa

Thomas Rotherham College Briggs Nigel

Thurrock College Wallace John

Tile Hill College Harris Steve, Galliers M

Totton College Joiner Susan, Joiner Michael, Hiscock Jill, Evans Anne

Tower Hamlets College Zera Annette

Trowbridge College Bright George, Maddocks Alun

Truro College Burnett Jonathon, Stansfield P J

Turnshaws Special School/What Next Staves L

TVEI Regional SEN Network (Yorkshire and Humberside) Broadhurst Marion

Tynemouth College Sunderland Mameen

Umbrella Preedy Susan

University of East London Corbett Jenny

University of Huddersfield, School of Education Swindells David

University of Leeds Chamberlain Anne

University of Liverpool Haworth Sarah

University of London Institute of Education Dee Lesley

University of Newcastle Dyson Alan

University of the West of England, Training & Research Associates Woodward Elizabeth

Users Forunl, Kempston Centre, Bedfordshire Doyle Barbara

Visual Impairment Support Team, Special Needs Teaching Service Weaver Bridgid

Wakefield College Constantine Anne

Waldon Association, The Beard Peter

Walsall Community Health Trust, St Margarets Hospital Jones Lorraine

Waltham Forest College Henderson Carrie

Wandsworth Adult College Watson Elizabeth

Warminster & District Society for Mentally Handicapped Children and Adults Burden Veronica

Warrington Collegiate Institute Drewe Sylvia, Harthill AM

Warrington Community Care Halliwell David D

Warrington Day Centre Lockwood Ena

Warrington MIND Kerrigan A T

[page 255]

Warwickshire Careers Service Morgan Jean

Warwickshire Social Services King Margaret

WCC Social Services Department Sarson P

Welcome Ear Club, Affliated to Hearing Concern Baxter Evelyn

West Berkshire Priority Care Service, NHS Trust Hutchinson Josephine

West Cheshire College Maynard Carol

West Cumbria College Craine Lynn

West Hertfordshire College Evans Tim

West Hertfordshire College

West Kent College Meadows Danny

West London Healthcare NHS Trust Sherwood S

West Midlands Autistic Society Ltd Morgan Hugh, Edwards Gwenn

West Midlands Autistic Society/Oakfield House Autistic Community Morgan Hugh

West Pennine Health Authority Elton Peter J

West Suffolk College of Further Education Carmichael Andy, Lally Ann, Pederson VVendy

West Thames College Gibbons Susan

Westminster College Burgess Carol

Weymouth College Buckley Trevor

Whitby Community College Gwinnell-Smith Gary

Wigan and Leigh College Corner Roy, Johnson Barry, Saldanha Jane, Scapens Dianne, Turner H P

Wightlink IOW Ferries Ltd Williams M

Wigston College, Link into Learning Fieldsend Judith

Wilberforce College Howard P

William Morris House Wooding Thomas Thorten

Wiltshire Careers Guidance Services Curbishley Lesley

Wiltshire LEA Harper T J

Wirral Metropolitan College Shackleton Jenny, Welch Anne

West Midlands Access Federation, University of Wolverhampton Donnelly Enda

Woking Sixth Form College Nevett Brenda

Wolverhampton Health Care Girach M H

Wolverhampton LEA Phillips Ian

Wolverhampton Mencap Polack Margaret

Wolverley NHS Trust Close Ann

Woodhouse Sixth Form College Drescher Gillian

Woodlands School Forde S J

Worcester College of Technology Wilkins C D

Worcester Sixth Form College

Workers Educational Association Munby Zoe, Hall Dorothea M

[page 256]

Wulfrun College Mothersdale G K, Tomlinson Wayne

Wyke Sixth Form College Rodmell Jo

Yearsley Bridge Centre Members Council

Yeovil College Chiffers Andrew

York College of Further Education and Higher Education Smedley Jane

Young Enterprise Hallwood Gretl

[page 257]

Responses from individuals

Allen Barbara parent(s)

Allen William person with learning difficulty/disability,

Robert Callard lip-reading tutor

Allerton Juliet lip-reading tutor

Allibone Frederick George person with learning difficulty/disability

Anderson H R A parent(s)

Anderson I parent(s)

Appleton Janet parent(s)

Atkinson Lyn parent(s)

Bainbridge parentis)

Baines Christine Linda person with learning difficulty/disability

Baker Magnus Alistair person with learning difficulty/disability

Barrett Patricia person with learning difficulty/disability

Baruch Lucy R person with learning difficulty/disability

Bennet Avril person with learning difficulty/disability

Bentley Barbara person with learning difficulty/disability

Boast Roy S person with learning difficulty/disability

Bonney May/Michael parent(s)

Bonser Jonathan Andrew student teacher

Bowles Reginald person with learning difficulty/disability

Bradshaw I parent(s)

Bramble Anna support tutor for dyslexic students

Brooks Beryl person with learning difficulty/disability

Bubb Elizabeth person with learning difficulty/disability

Bullock Ernest Paul Charles person with learning difficulty/disability

Burnett Sarah trainer

Button Joanne parent(s)

Charters Frances PGCE student

ClarkC A parent(s)

Clissold Shirley Ann person with learning difflculty/disability

Collie Madeleine person with learning difficulty/disability

Comtois Fernand parent(s)

Corcoran Leo retired lecturer

Cordery Joan person with learning difficulty/disability

Cowley Madeleine parent(s)

Cox Simon person 'with learning difficulty/disability

Crees Diana Christine person with learning difficulty/disability, retired teacher

Croft A person with learning difficulty/disability

Crossland Ann parent(s)

Davey Gillian/Godfrey parent(s)

Davies Margaret Ann parent(s)

Davies T V person with learning difficulty/disability

Dawe S parent(s)

Dawson I parent(s)

Eagland Elizabeth person with learning difficulty/disability

Ehsansullah Lillian person with learning difficulty/disability, advocate

Evans Pauline person with learning difficulty/disability, parent(s)

Farrington Gail Mary Ann student

Fisher Anne parent(s)

Forward T parent(s)

Gentle Chris/Marion parent(s)

Gilbert James Ernest person with learning difficulty/disability

Gillam E carer

Grieves James, Lamdie parent(s)

[page 258]

Griffiths lip-reading tutor

Grove John S

Haigh Hanson person with learning difficulty/disability

Haigh Irene person with learning difficulty/disability

Harkness Stuart person with learning difficulty/disability

Harvey Majorie person with learning difficulty/disability

Hayes Ivan person with learning difficulty/disability, carer

Hazlett Robert and Patricia parent(s)

Heapy Dorothy person with learning difficulty/disability

Hefferman Olive person with learning difficulty/disability

Henley Jane parent(s)

Henry Charlie

Heys F retired special needs teacher

Hill A E F

Holme Helen Michelle person with learning difficulty/disability

Holroyde Mary person with learning difficulty/disability

Hopkins Veronica parent(s)

Horrex David person with learning difficulty/disability

Howe Pauline Hazel person with learning difficulty/disability

Hulbert I parent(s)

Hutt Ralph person with learning difficulty/disability

Johnson A C professional

Johnson Margaret H retired college principal

Jones Edward Charles person with learning difficulty/disability

Jones Stephen

Jordan Linda/Mark parent(s)

Josephs Rosalina lip-reading tutor

Knapman David consultant educational psychologist

Leeming David parent(s)

Lemer Miriam parent(s)

Lewis Christopher Martin educational psychologist

Lomas Sheila person with learning difficulty/disability

Mackie Ada parent(s)

Marsh Carol & John parent(s)

Massey Jack person with learning difficulty/disability

McGechan Colin & Joyce parent(s)

Merriott Pamela/Torben parent(s)

Montgomery Eileen person with learning difficulty/disability

Moore Beryl adult placement carer

Morris Carl Allen William person with learning difficulty/disability

Morris Rachel Josephine carer

Mumtaz Adeeba parent(s)

Neal M A person with learning difficulty/disability

Newby Walter David person with learning difficulty/disability

Newby/Smith Michael/Claire person with learning difficulty/disability, parent(s)

Nicholas Jill Margaret parent(s)

Nurse Mary Elizabeth person with learning difficulty/disability

Oakes B person with learning difficulty/disability

Paintin Ivy N person with learning difficulty/disability

Pearson Ethel E person with learning difficulty/disability

Perks Michael Anthony person with learning difficulty/disability

Polack Margaret/It A parent(s)

Portal Kate

Powell Michael Brian person with learning difficulty/disability

Priddle Annette Diane person with learning difficulty/disability

Prince David person with learning difficulty/disability

Prince Valerie Joan parent(s), schoolteacher

Rees Alan carer

[page 259]

Ripley Joseph Raymond person with learning difftculty/disability

Ritchie Angela parent(s)

Rixter Penny head of support unit

Roberts Graham person with learning difficulty/disability

Roberts Keith person with learning difficulty/disability

Roberts Peter person with learning difficulty/disability

Robinson Lesley parent(s)

Rogers Roy person with learning difficulty/disability, freelance researcher

Scaife Leslie, William parent(s)

Sellman Ingrid lip-reading tutor

Sheen Raymond/Carole parent(s)

Shrubshall Bernadette

Slowey Paul person with learning difficulty/disability

Smith I A person with learning difficulty/disability

Spedding Helen lip-reading teacher

Stone Henry William person with learning difficulty/disability

Summers Mark person with learning difficulty/disability

Sutton E parent(s)

Sutton Malcolm parent(s)

Swallow Candice, Jade person with learning difficulty/disability

Symes P I other

TerryShirley person with learning difficulty/disability

Thompson Jean person with learning difficulty/disability

Thompson Merry lip-reading tutor

Thomson T A person with learning difficulty/disability

Tombs Anne person with learning difficulty/disability

Tomkins A carer

Trenchard P I parent(s)

Turner I parent(s)

Veall Roger M person with learning difficulty/disability

Vernon Mary

Waine Judith special needs educator, SLD team leader

Warne Brian person with learning difficulty/disability

Watkins Dorothy person with learning difficulty/disability

Watson F M person with learning difficulty/disability

Watts Colin James person with learning difficulty/disability

Watts Sarah person with learning difficulty/disability

WheeldonJean person with learning difficulty/disability

Whitehead Christine Elizabeth lip-reading tutor

Woodger John Page person with learning difficulty/disability

Wooding Vera Mary parent(s)

Wright K C person with learning difficulty/disability

Wring Sheralun person with learning difficulty/disability

Yarnell Joan person with learning difficulty/disability, student

Young Hilary Anne person with learning difficulty/disability

Young S E parent(s)

Younger Sadie McW person with learning difficulty/disability

[page 260]

Appendix 2 to Annex F: Outline of Evidence Strategy

Introduction

1 The committee gathered evidence in seven ways:

- its call for evidence

- commissioning research, including a review of previous research and a survey of provision

- commissioning a series of workshops for students with learning difficulties and/or disabilities

- attending conferences and workshops and holding seminars for particular groups

- establishing short-life working groups to consider particular issues

- visiting colleges and other organisations, in England and elsewhere

- inviting individuals and representatives of organisations to give oral evidence.

2 The committee also took the decision to publish some of its work during its three-year life. These publications are listed at the end of this appendix.

The call for evidence

3 The committee's call for evidence was sent to over 6,000 recipients. The evidence received in response took a variety of forms, including video-tapes, reports, research, students' work, personal letters and official statements. Most of this evidence was received by September 1994. Responses to the call for evidence were received from the following:

- individuals with learning difficulties and/or disabilities

- their parents/carers and/or advocates

- further education colleges

- LEA maintained schools

- specialist establishments for those with learning difficulties and/or disabilities

- local education authorities

- local authority social service departments

- careers services

- health authorities

- Training and Enterprise Councils

- voluntary organisations

- training and rehabilitation organisations

- other individuals concerned about the provision of further education for students with learning difficulties and/or disabilities.

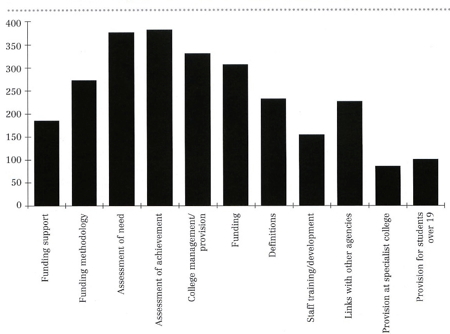

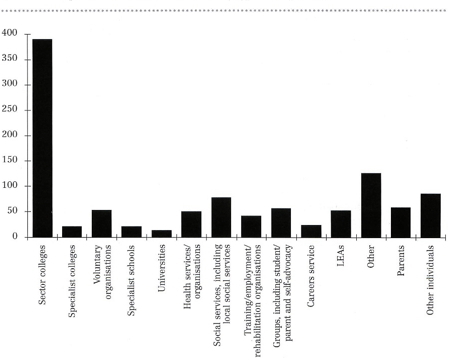

4 The 1,091 responses were analysed by two consultants who reported their findings to the committee. Figure 1 at the end of this appendix shows the number of responses focusing on each of the issues raised and figure 2 the number of responses according to the type of respondent. The call for evidence asked for information about: what 'disability and/or learning difficulty' means; assessment; the extent to which colleges cater for students' needs and the needs of communities; funding arrangements and their impact; specialist support services; the role of health and local authorities and joint working; and on the quality of provision and of students' experiences.

[page 261]

5 The 10 main issues raised by the respondents were:

i. funding support; (mentioned by 17% of all respondents). Concerns included the Council's additional support funding mechanism and funds for external and specialist support;

ii. funding methodology; (mentioned by 26% of all respondents). Concerns included funding for support; the link between funding and accreditation; time-limited funding; and guidance for advisers, teachers and co-ordinators;

iii. assessment; (mentioned by 35% of all respondents). Concerns included the costs and funding of assessment; the importance of focusing on individuals rather than the demands of the curriculum or available resources; the role of specialists, such as educational psychologists; and the importance of ensuring effective transition into further education and beyond;

iv. assessing achievement; (mentioned by 36% of all respondents). Concerns included the links between achievement and funding; the focus on accreditation; and the development of nationally-recognised accreditation schemes that offer real progression;

v. college provision and management; (mentioned by 31% of all respondents). Concerns included structures which best ensure good-quality further education provision; integrating and managing progression; gaps in provision, especially for: students with profound and complex learning difficulties, adults with learning difficulties and/or disabilities, students with sensory impairment, students with dyslexia or specific learning difficulties; and how to manage teaching, learning and curriculum development;

vi. training and staff development; (mentioned by 14% of all respondents). Concerns included the need for staff development and disability awareness training;

vii. definitions; (mentioned by 22% of all respondents). Concerns included differences in the definitions used by different agencies and assistance in applying them; and concerns about labelling and categorising students;

viii. links with other agencies; (mentioned by 21% of all respondents). Concerns included uncertainty about the responsibilities of various agencies involved in further education and support for students, especially for those over the age of 19;

ix. provision at specialist colleges; (mentioned by 8% of all respondents). Concerns included the Council's procedures for funding places;

x. provision for students aged over 19; (mentioned by 9% of all respondents). Concerns included uncertainty about the criteria for inclusion of programmes within the scope of schedule 2 to the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.

New research, including a review of research and survey of provision

6 As its first task, the committee commissioned an overview of research from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER). The review covers national and international research, definitions, provision, assessment, funding, support systems, quality and achievement, transition and inter-agency working. The review examines nine key questions and includes a full bibliography. It found many gaps in the research and offers suggestions of where further research is needed. The report has been published and a copy sent to every college. The full report is available from NFER.

7 The mapping exercise, commissioned by the committee from the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) following

[page 262]

competitive tender, set out to find the extent of the need for further education and the current provision for students. The committee commissioned the survey because there was no up-to-date national information. The aim of the project was to:

- estimate from existing information the number of people aged 16 and over (in each region) in England with learning difficulties and/or disabilities

- estimate the extent of their participation in further education

- identify the factors which influence their participation, and

- estimate any unmet educational need.

8 The project began with a review of national research on the numbers of people with disabilities or learning difficulties, identifying existing and significant national data sets and analysing each of them to form some general figures relating to the incidence of disability within the general population. However, much of the data overlapped. Much of it also used different definitions. It was therefore not possible to deduce the likely need in the general population, a proportion of whom might reasonably be thought to require further education. The second part of the research surveyed the provision made in colleges through a national questionnaire. It involved a pilot survey undertaken in 20 colleges in Spring 1995 and a postal questionnaire piloted with a sample of 100 sector colleges in the summer term 1995.

9 The main survey itself was launched in October 1995 and concluded by mid-March 1996. It covered all sector colleges and a sample of external institutions and related to all students enrolled on 1 November 1995. The response rate was just over 60% (274 colleges). The distribution of responses by type of college and region was statistically representative of the sector as a whole, but higher response rates were achieved from larger colleges. The committee drew heavily on this research in its report, particularly in the chapter 4. The research is published as a companion volume. The IES also completed for the committee a preliminary project on how further education participation could be measured and what is already known about what influences that participation by people with learning difficulties and/or disabilities. At the time of publication of this report, work was under way to develop a practical guide for colleges. It will help them to better assess needs in their local community and to monitor participation more accurately. This work is being funded by the Council on behalf of the committee and the widening participation committee.

Seminars and workshops for people with disabilities and/or learning difficulties

10 The views of further education students with disabilities and/or learning difficulties were sought through a series of workshops commissioned from Skill: The National Bureau for Students with Disabilities following competitive tender. Skill worked in partnership with several agencies, including Social and Community Planning Research (SCPR) which wrote the report. From a careful sifting of around 2,000 applications, 266 personally invited students took part in 10 workshops at venues around the country. Students told the researchers that they wanted:

- more opportunities to give their views about their experiences of further education

- more opportunities to develop self-advocacy skills in order to have a say at college

- to feel valued and welcomed at colleges

- not to be labelled as having a disability or learning difficulty, though recognised the value of this when resources were required

- recognition that they attended college for the same reason as other students - for experience, skills and qualifications

[page 263]

- teachers to listen to their aspirations and take them seriously

- to find out more about their course before they came to college

- to know when assessment was taking place, and its purpose

- additional support and specialist equipment to be in place straight away and for it not to make them feel different from other students

- teachers to know about their disability or learning difficulty and to understand how it might influence their learning

- teachers to use a variety of approaches in their teaching, to give regular constructive feedback and to get to know them well

- opportunities to learn alongside other students

- to get into and move around college with the same ease and freedom as other students; and to travel to college and between sites quickly and effectively.

11 The full report has been sent to every college. Copies are available from Skill.

Attendance at conferences and workshops, and holding seminars for particular groups

12 Seminars, conferences, workshops and meetings attended by committee members, the staff team and the chairman allowed more evidence to be taken from particular groups and for work done by the committee to be shared with others. These events included regional and colleges' seminars; national conferences and events organised by voluntary organisations.

13 The committee held seminars to obtain the views of particular groups of people. These included:

- a seminar for representatives of the research community to consider how to map provision and participation (February 1994)

- a seminar on assessment in sector colleges (February 1994)

- two meetings for organisations providing and receiving support services (February 1994, January 1995)

- a meeting for voluntary organisations on the kind of evidence that they might submit to the committee (May 1994)

- a seminar on assessment for placements in specialist establishments (May 1994)

- a seminar for parents of students with a learning difficulty and/or disability and parents' organisations (July 1995)

- a seminar with colleges to test the committee's approach (July 1995)

- a meeting for advocates and self-advocates working in or involved in further education (September 1995)

- a seminar for those using and managing enabling technology (February 1996)

- a seminar on legal issues (March 1996).

Short-life working groups to consider particular issues

14 At its early meetings the committee

established working groups, co-opting individuals with particular expertise and knowledge. The groups reported to the committee through written reports. Working groups considered:

- assessment of individual needs, assessment of students' learning and achievements

- assessment to offer advice to the Council's tariff advisory committee on aspects of the funding methodology

- support systems and support services for students

- inter-agency collaboration, including the role of local authorities and health services

- definitions, including what 'disability and/or learning difficulty' means.

[page 264]

Visits to colleges and other organisations, both in England and elsewhere

15 A full list of visits undertaken by the committee, its staff and the chairman is given at annex F. A summary of the findings of visits to other countries is given at annex C.

Individuals and representatives of organisations invited to give oral evidence

16 The committee sought oral evidence from a number of organisations. The Council offered advice on:

- the quality of further education provision for students with learning difficulties and/or disabilities in sector and specialist colleges

- funding arrangements for students with learning difficulties and/or disabilities

- the recurrent funding methodology, 1995-96 consultation

- funding allocation issues

- placement of students in independent colleges

- strategic planning

- the role of its regional committees

- mapping provision and participation in further education for students with learning difficulties and/or disabilities.

17 Evidence from other organisations included advice on:

- the further education curriculum, from Geoff Stanton, Further Education Unit

- the Education Act 1993; schools matters and implications for the work of the committee, from the Department for Education and Employment

- the committee's thinking about inclusive learning, from people involved in the disability movement

- international evidence, from Mr John Fish, consultant (formerly OECD)

- specialist colleges, from the NATSPEC advisory committee, students at specialist colleges and their tutors

- employment, training and careers guidance, from the DfEE, together with the chief executive, Rathbone C.I.

- disability, learning difficulty and adult learning, from the chief executive and research and development colleagues, National Institute of Adult Continuing Education; and from the principal and colleagues, North Warwickshire College

- curricular, organisational, managerial and staff development, from the chief executive together with the development officer, Further Education Development Agency

- college strategic planning, from the principal and colleagues, Blackburn College

- the implications of the committee's work for teacher education and staff development, from the SENTC/Skill further and higher education monitoring group

- OFSTED and the new schools inspection system, and findings from inspection related to provision for adults and young people, from HMI.

Evidence to working groups included:

- findings of the NFER survey on collaboration, from Karen Maychell, NFER

- the local management of transition, from Barry Stockton, consultant to FEU

- definitions of learning difficulty/disability from social care and training perspectives, from Stella Dixon, FEU and John Curtis, Skill

- the accreditation of achievement, from Elsa Dicks, NCVQ; Colin Walker, BTEC; Terry Davis, the Associated Examining Board; and Nancy Braithwaite, SCAA (Sir Ron Dearing's review of the 16 to 19 qualifications).

[page 265]

Figure 1. Number of responses to the call for evidence by issue raised

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

Figure 2. Responses to the call for evidence by type of respondent

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 266]

Committee Publications

Disability, Learning Difficulties and Further Education: Call for Evidence from the FEFC Committee, FEFC, Coventry February 1994

Disability, Learning Difficulties and Further Education: Work in Progress by the Council's Committee, FEFC, Coventry May 1995

Beachcroft Stanleys Duties and Powers: The Law Governing the Provision of Further Education to Students with Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities: A Report to the Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities Committee, London, HMSO, 1996

J. Bradley, L. Dee and F. Wilenius Students with Disabilities and/or Learning Difficulties in Further Education: A Review of Research Carried out by the National Foundation for Educational Research, Slough, National Foundation for Educational Research, 1994

Nigel Meager, Ceri Evans and Sally Dench (of The Institute for Employment Studies) Mapping Provision: The Provision of and Participation in Further Education by Students with Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities: A Report to the Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities Committee, London, HMSO, 1996

SCPH Student Voices: The Views of Further Education Students with Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities: Findings from a Series of Student Workshops Commissioned by the Learning Difficulties and/or Disabilities Committee, London, Skill: National Bureau for Students with Disabilities, 1996