[page 385]

CHAPTER 7

Language and Language Education

1. Introduction

Linguistic Diversity

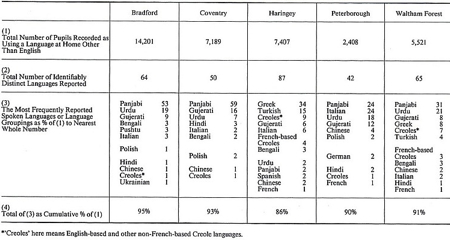

1.1 The English language is a central unifying factor in 'being British', and is the key to participation on equal terms as a full member of this society. There is however a great diversity of other languages spoken amongst British families in British homes. The report from the Linguistic Minorities Project (1) shows, for example, that in Bradford 14,201 pupils spoke between them some 64 languages other than English at home, and in Haringey 7,407 pupils were found to speak a total of 87 'other' languages. In order to lay the foundations for a genuinely pluralist society the education system must we believe both cater for the linguistic needs of ethnic minority pupils and also take full advantage of the opportunities offered for the education of all pupils by the linguistic diversity of our society today. To avoid misunderstandings, it should be said straightaway that this does not, as will become apparent, mean that teaching of school subjects in languages other than English, save for one area, the modern languages curriculum - see paragraph 3.19.

The Task for Education

1.2 Language and language education have long been the subject of attention by educationists at all levels. Where there has been a 'multi-cultural' dimension to this debate it has usually been perceived in narrow and discrete terms, initially as concerning the 'problem' of teaching English to children for whom it is not a first language, and more recently, as responding to the demands of certain ethnic minority communities for their children to be taught their 'mother tongues'. We believe that the language needs of an ethnic minority child should no longer be compartmentalised in this way and seen as outside the mainstream of education since language learning and the development of effective communication skills is a feature of every pupil's education. In many respects, ethnic minority children's language needs serve to highlight the need for positive action to be taken to enhance the quality of the language education

(1) 'Linguistic Minorities in England.' A report by the Linguistic Minorities Project. University of London Institute of Education. 1983. (The Linguistic Minorities Project (LMP) was set up in 1979 at the Institute of Education and was funded by the Department of Education and Science for a period of three and a half years. Its function was to investigate patterns of bilingualism in different parts of England, and to assess the educational implications of linguistic diversity.)

[page 386]

provided for all pupils. We feel that a broader approach to language education would be justified even if we did not have in this country substantial communities for whom English is not a first language. Since however we have the additional resource within our society of bilingual, and in many cases, multilingual communities, it is surely right and proper that the education system should seek to build on the opportunities which this situation offers. Linguistic diversity provides the opportunity for all schools, whether monolingual or multilingual, to broaden the linguistic horizons of all pupils by ensuring that they acquire a real understanding of the role, range and richness of language in all its forms.

'Linguistic Prejudice'

1.3 In considering the linguistic needs of ethnic minority pupils and the broader role of language education in relation to all children, it is difficult is isolate factors relating to language from the 'climate' of learning which exists in schools. The negative attitudes held towards ethnic minority communities which we discussed in Chapter Two can we believe often manifest themselves in the form of 'linguistic prejudice' against the languages of these communities which tend therefore to be regarded as of low status. It is indeed a powerful lesson to those people who claim that Britain is already a just and pluralist society to find how readily 'not speaking English' or 'not speaking English 'properly' seems to be taken to indicate that an individual is inadequate and in some way inferior. When such attitudes exist in a school environment, not only on the part of teachers but also ethnic majority pupils, and are left uncorrected, and also permeate much of the policy making in this field, it is inevitable that the educational experience of an ethnic minority pupil for whom English is not a first language may be influenced in a very direct and immediate manner.

This Chapter

1.4 In this chapter, we begin by considering how the educational needs of pupils for whom English is not a first language have been perceived by the education system and the various forms of provision which have been adopted to cater for these needs. We focus particularly on the role of language centres and the extent to which we believe such forms of 'separate' provision are in keeping with our philosophy of 'Education for All'. We then go on to discuss the role of the education system in relation to the maintenance and support of the languages of ethnic minority communities - the 'mother tongue debate' - an issue which has become increasingly central to the multi-cultural field in recent years. Finally, we look at two broader aspects of language education bearing on the needs of all pupils, both ethnic minority and majority - the concept of language across the

[page 387]

curriculum, and the need to enhance pupils' awareness of the diversity of languages and language forms now present in our multiracial society.

2. English as a Second Language

Changing Attitudes

2.1 As we have recalled in Chapter Four, the major response of the education system to the arrival from the late 1950s onwards of growing numbers of ethnic minority pupils was the provision of intensive English teaching for those for whom this was not a first language. The English language was seen as the key to assimilation and to the newcomers 'adapting' to the British way of life and it seems to have been assumed that the children's own languages would simply die out and be replaced with English. Whilst it may not have been an explicit aim on the part of schools to eradicate the home languages of ethnic minority pupils this was certainly accepted as a desirable development and it is clear, in retrospect, that the full implications of the policies being pursued were seldom realised. The shift towards integrationist thinking brought about a greater awareness of the backgrounds of ethnic minority pupils including their languages. Whilst this meant that the existing linguistic skills of children were less likely to be ignored entirely, there was still little sign of the education system as a whole actively valuing these skills as of relevance to the pupil's general progress. In recent years, however, with the development of the concept of multi-cultural education, the emphasis has increasingly been on developing the whole range of a child's linguistic resources and, in the case of those children for whom English is not a first language, on not undermining their existing linguistic resources in teaching them English. This wider view of the role of language in the educational experience of an ethnic minority pupil appears however in some respects to have impinged only marginally on provision for teaching English as a second language (E2L), much of which has in fact, in terms of its underlying aims and assumptions, changed little from its early days.

Forms of Provision

2.2 The means by which LEAs have sought to cater for the E2L needs of pupils in their areas have varied widely, ranging from the employment of teams of peripatetic staff serving a number of schools by withdrawing pupils for specialist help, to the establishment of separate language centres catering for children of all ages, either on a part-time basis - having been withdrawn from their normal schools

[page 388]

- or on a full-time basis - before being placed in mainstream schools at all. This pattern was indicated by the findings of a DES Survey (2) which found that in 1983:

' .... some 104,000 school age children from homes where English is not the first language receive special help with English from the equivalent of 1,900 full-time specialists together with a large number of ordinary class teachers. The provision of such teaching takes a variety of forms ... Reception and language centres still account for 7% of the provision, but most children now receive their English language tuition either in small specialist classes within the school (70%) or by other means within the school (23%).'

Confusion with English as a Foreign Language

2.3 Despite the variety of present day provision, E2L teaching has traditionally been seen as a form of 'marginal' provision which is the responsibility of specialist teachers coping with a particular educational need. Non-specialist teachers have been led to believe that they have little or no role to play in the language development of children from homes where English is not the first language. This view that E2L needs are not the responsibility of the ordinary classroom teacher arises in part at least from the fact that many E2L teachers were originally teachers of English as a foreign language abroad and were thus not seen as part of the mainstream teaching force of this country. It is perhaps understandable that in the early years of large scale immigration such teachers were considered to be best qualified to cater for the language needs of ethnic minority pupils, and full credit must be given to the efforts of many of them in coping with large numbers of children, often with limited resources and support. There is however a marked difference between teaching English as a foreign language abroad and, as in the case of E2L work, teaching the national language of this country to children who will subsequently have to function in this language throughout their educational experience and their adult lives. It must also be recognised that teachers who have previously taught overseas may be likely to regard ethnic minority children in this country as 'foreign' rather than British. These teachers may also be seen as, and indeed may see themselves as, 'experts' on the home background of such children and their families, and may, through seeking, for example, to relate their knowledge of life in Pakistan to the needs of a Pakistani

(2) DES Memorandum on Compliance with Directive 77/486/EC on the Education of Children of Migrant Workers. February 1983.

[page 389]

family in Bradford, serve, albeit unknowingly, to perpetuate inaccurate and out of date stereotypes of ethnic minority communities.

Language Centres

2.4 The form of E2L provision most in keeping with the assimilationist phase of thinking is clearly separate language centres. Although originally conceived as a form of 'positive discrimination' designed to help children whose first language was not English reach the same level of fluency in English as their peers, the thinking behind these centres can we believe in retrospect be seen as an example of institutional racism which, whilst not originally discriminatory in intent, is discriminatory in effect in that it denies an individual child access to the full range of educational opportunities available - in the case of full-time centres by withdrawing them totally from the mainstream school and with part-time provision by requiring them to miss a substantial part of the normal school curriculum.

2.5 The main arguments in favour of language centres can be seen as organisational and administrative in terms of the convenience of bringing together in one place all children with particular needs so that specialist staffing and resources can be focused there. The availability of grants under Section 11 of the Local government Act 1966 may also have encouraged LEAs to establish and retain language centres since they are able to claim grant at a rate of 75% of the salary of every teacher employed in such a centre thus making it cheaper to provide a more generous staffing ratio than if the children were in a number of schools. The arguments against such centres are primarily on socio-educational grounds, as highlighted in the following extract from evidence submitted to us:

'The problems of sending pupils to language centres, to my mind, hinge around the questions of peer group relationships and of continuity of timetabling. Children make and consolidate relationships begun in the classroom, in the playground, in registration time, and at lunchtimes. That whole social life is an important part of the pupil's-eye view of the school. The role, presence and interventions of teachers are only part of that view. That is to say, there is a dialectical relationship between the way in which a pupil conducts him or herself in the playground and performance in the classroom; if a child misses half a school day (which includes the morning and afternoon breaks and a large part of the lunch-hour), then this will have a major effect on his or her school life. The feelings of marginality and exhaustion engendered by this kind of language teaching provision can easily be appreciated by teachers who themselves have worked on a peripatetic basis or in a split-site school. What

[page 390]

is a teacher in the main school to do when a child appears for one lesson and not the next because that's his or her time to go to the language centre? You do not have to be an ill-intentioned teacher to send a child to find a remedial teacher, or similar body, asking for him or her to be taught for that period. Bright, intelligent children can thus be spending the mornings in a language centre and the afternoons in a remedial department ... my argument is not that teachers don't care, nor that they are acting deliberately against children's rights to education. Rather that an off-site withdrawal system takes the whole question out of their hands.'

Withdrawal Within Schools

2.6 Where the language needs of children from homes where English is not the first language are met within mainstream schools through withdrawal into separate E2L classes, some of the extremes of isolation highlighted above can be avoided. There are nevertheless strong educational arguments against even this degree of segregation, as explained in the following extract from evidence to us:

'... second language learners should be in mainstream classes rather than the situation we have more commonly encountered where second language pupils are withdrawn to be taught away from the general run of mainstream activities. This more common situation not only institutionalises second language pupils to failure but also compounds the difference between second language pupils and other members of the community. Furthermore, on educational grounds, separation of second language learners from the curriculum followed by all the other pupils cannot be theoretically justified since in practice it leads to both their curriculum and social learning being impoverished, and thus both language and intellectual development is held up. It also means that the burden of joining in is always placed on the newcomers and never on those already established in the mainstream.'

Concern has been expressed for some years about the possible effects on E2L pupils of providing for their needs through any form of separate 'added on' provision and the view that their needs would best be encompassed within the mainstream curriculum has been gaining ground - as the 1975 Bullock Report (3) observed:

'... common sense would suggest that the best arrangement is usually one where the immigrant children are not cut off from the social and educational life of a normal school.'

(3) 'A Language for Life.' Report of a Committee of Inquiry under the Chairmanship of Sir Alan Bullock. HMSO. 1975

[page 391]

Status of E2L

2.7 One consequence of E2L provision having generally been organised on a withdrawal basis and dealt with by teams of identifiably specialist teachers, often working on a peripatetic basis, has been the effect on the status of the subject, its teachers and its pupils. All the E2L teachers to whom we have spoken, as well as many of the other educationists with whom we have raised this issue, have stressed the low regard in which the subject is held. The teachers have frequently been accused by their colleagues as 'taking the easy option' since they generally teach small groups of pupils, and at secondary level a non-examination subject. Peripatetic staff are often regarded as 'part-timers' and are not seen as having a role in decision-making since they are not accepted as part of the whole school staff. As one E2L teacher explained to us:

'... in secondary schools, English departments did not see any relationship between their work and E2L provision which was seen very much as a "sub-subject".'

E2L provision often seems to be mistakenly regarded simply as a form of remedial work with lack of English being in effect equated with lack of ability and the pupils themselves being stigmatised as 'failures'.

Arguments Against 'Separate Provision'

2.8 The main arguments against E2L provision being made either in language centres or in separate units within schools can be summarised as follows:

- the limitations on the breadth of curriculum which a language centre or unit can offer and the inherent injustice of denying any pupil access to other subjects until he or she has mastered English;

- the absence in many cases of direct links between the language centre or unit and the mainstream of school life which means that the work being done does not mirror that of the school and that the language needs perceived by class teachers are not necessarily met by the E2L specialists;

- the possibly negative effect on a pupil's progress in learning English of mixing primarily or even solely with children for whom English is not a first language;

[page 392]

- the possible effects on a child's socialisation and developing maturity of being separated from his or her peers and away from the 'social reality' of the school;

- the inevitable trauma for a child of entering the English-speaking environment of the mainstream school, is merely postponed and in no way avoided;

- mainstream school teachers are discouraged from regarding ethnic minority pupils' language needs as their concern and are indeed encouraged to regard E2L work as a whole as of low status.

2.9 In the light of our aim of developing an education system which lays the foundations for a genuinely pluralist society, we believe it is essential to consider carefully how best to cater for the language needs of pupils for whom English is not a first language - as one group of E2L specialists put it to us in their evidence:

'... the issue we are addressing is not just a question of what is best for second language learners. It is a larger one: that of what organisations and strategies have the best potential for creating for all learners equal access to the starting points of their learning and understanding.'

Our View

2.10 We are wholly in favour of a move away from E2L provision being made on a withdrawal basis, whether in language centres or separate units within schools. This view was shared by many of the E2L specialists whom we met who argued strongly for the formulation of coherent policies for meeting the needs of second-language learners through integrated provision within the mainstream school as part of a comprehensive programme of language education for all children. We recognise that in the case of pupils of secondary school age arriving in this country with no English some form of withdrawal may at first be necessary. Nevertheless, we believe that this should take place within the mainstream school. We have already emphasised our fundamental opposition to the principle of any form of 'separate provision' which seeks to cater only for the needs of ethnic minority children since we believe that such provision merely serves to establish and confirm social and racial barriers between groups. We would therefore hope to see 'E2L' being viewed as an extension of the range of language needs for which all teachers in schools, should, provided they are given adequate training and appropriate support, be able to cater.

[page 393]

Pre-School Provision

2.11 In our interim report we highlighted the importance of pre-school provision, particularly in the form of nursery education, for the West Indian child and indeed for all children. We urged, for example, that at a time of falling school rolls, LEAs should seek to convert former primary school premises for nursery use and that local authorities should use all available means to inform parents of the nursery education and day care facilities available in their areas. The further evidence we have received since submitting our interim report has we believe confirmed the crucial role of pre-school provision and we make no apology for endorsing our earlier recommendations. For the child from a home where English is not the first language, it is clear that nursery provision can be a particularly valuable stage of the overall educational experience and can we believe serve to ease the sometimes traumatic transition between the home and school.

Primary Level

2.12 As we explain later in this Chapter, we would expect to see all schools developing explicit policies on language education, as advocated in the Bullock Report. Within this overall framework, we would see the E2L needs of pupils in primary school being met within the normal classroom situation by class teachers. To enable these teachers to develop the necessary skills to take on this task, there clearly needs to be an expansion of appropriate in-service provision, preferably school-based. We would also expect the staffing levels of schools with substantial numbers of pupils with E2L needs to be enhanced in order to allow some teachers to develop a particular expertise in language work through further in-service courses and consultation with their LEAs advisory service. These teachers could then work in classes alongside their colleagues to give particular support to 'beginners' in English, not through separate provision but within the framework of the activities being undertaken by the whole class. Such teachers would be able to help not only pupils with E2L needs but also any pupil with language difficulties - a broader role which has not previously been possible within the separate structure of E2L. Clearly existing teachers with skills in the field of language, such as specialist E2L staff or bilingual teachers with knowledge of the appropriate mother tongues, would be particularly suited to the role we have in mind. (In areas where specialist language centres are being phased out there may be a need for structured 'staff exchanges' between the centres and mainstream schools during the changeover period as a form of in-service provision for all.) Where the scale of language need is not sufficient to justify enhanced staffing on a permanent basis, an LEA advisory teacher should nevertheless be available to visit schools on a regular basis to work with class teachers.

[page 394]

2.13 An indication of the approach outlined above working in practice was provided by a combined first and middle school we visited:

'In terms of the mother tongues spoken by the majority of the children (Punjabi, Gujerati, Urdu), the school may be said to be one where English is the second language, although for the children English is the principal medium for their learning while they are at school. All the staff are therefore by definition teachers of English as a second language. Seven staff (5 in the first school, 2 in the middle school) possess an E2L qualification; one member of staff is currently taking the RSA Diploma Course in the Teaching of English as a Second Language in Multi-cultural Schools; and a further teacher is studying for a post-graduate diploma in Applied Linguistics. While the school has therefore a valuable leavening of staff with special E2L qualifications, all teachers in the school need this kind of expertise and understanding to extend, develop, and enrich the children's language. In the first school ... the specialist E2L teacher does not at present have a class of her own. Children in need of specialist E2L language tuition are fully integrated into the 4 vertically-grouped 1st and 2nd Year classes and the teacher is deployed over all 4 classes doing group work, so that as many children as possible can receive her help, while the children themselves benefit through the interaction with other children who provide a more stimulating language environment. In the middle school, although the E2L Scale post holder has her own class, she is able to offer advice and support to other colleagues, as well as buy in suitable teaching materials.'

Secondary Level

2.14 Similarly in secondary schools we believe that pupils with E2L needs should be regarded as the responsibility of all teachers, although there is clearly a role for particular language specialists on a school staff who can offer support and advice both to their colleagues and to pupils with language difficulties. Within the broader view of the role of a 'language coordinator' and a school's English department which we envisage later in this Chapter, we would see English departments of schools with substantial numbers of pupils with language needs including E2L specialists who would be able not only to contribute to the development of a general policy on 'language across the curriculum', but, more specifically, to work alongside their subject colleagues in the classroom situation.

'Team Teaching' Approach

Such an approach to meeting language needs has already been adopted in a number of schools we have visited and is generally referred to as the

[page 395]

'co-operative' or 'team teaching' method. An indication of the issues which need to be considered in adopting a team teaching approach to E2L provision, together with a 'checklist' of aims and objectives for both the specialist teacher and the subject teacher, are provided in a very helpful paper at Annex A, prepared by the staff of one of the schools we visited. The challenge presented to both the mainstream staff and the specialist teacher(s) involved in implementing such an approach should clearly not be underestimated and this is illustrated in the further extract from evidence - attached as Annex B to this Chapter - which describes how one school moved from E2L teaching on a withdrawal basis to provision within the 'normal' curriculum.

Mainstream Attitudes

2.15 We recognise that there is a considerable way to go before this broader concept of responsibility for language needs gains general acceptance. It would hardly be in the interests of second language learners to lose the specialist help of E2L teachers and to simply be left to 'sink or swim' within the mainstream classroom situation without the necessary help and support. In view of the somewhat negative attitudes of some mainstream teachers towards E2L learners, especially the correlation of 'lack of English' with 'lack of ability', there clearly needs to be major shift in opinion in order to accord these pupils equal opportunities within the mainstream school. We have been very concerned by the number of times that E2L staff in language centres and units have described the hostility, not only of mainstream pupils but also of other teachers, towards their pupils when there have been attempts at joint activities. The broad policies of 'language across the curriculum' and the fostering of positive attitudes towards linguistic diversity which we recommend later in this Chapter are clearly essential therefore in creating the positive climate necessary for integrated E2L provision to become a reality.

'Second Stage' Needs

2.16 In their evidence to us, E2L teachers have often stressed that second language learners are 'ordinary' learners and that many of their language needs may in fact be shared, albeit to a lesser degree, by some ethnic majority pupils, especially those in inner urban areas or remote rural areas. This is particularly so in the case of what are generally termed 'second-stage' language needs, i.e. the need for an E2L learner who has mastered 'survival' English to be helped to extend his range and command of the language by applying it to various learning situations. The Bullock Report listed the following uses of language as essential in any child's language development:

'Reporting on present and recalled experiences.

Collaborating towards agreed ends.

[page 396]

Projecting into the future; anticipating and predicting.

Projecting and comparing possible alternatives.

Perceiving casual and dependent relationships.

Giving explanations of how and why things happen.

Expressing and recognising tentativeness.

Dealing with problems in the imagination and seeing possible solutions.

Creating experiences through the use of imagination.

Justifying behaviours.

Reflecting on feelings, their own and other peoples.'

The ability to use English in these complex ways lies at the heart of the educational process and without such skills a child, whether ethnic minority or ethnic majority, can be condemned to underachieve in relation to the academic goals set by the system. As we explain later in this Chapter, we would like to see all teachers having a far greater understanding of the role of language in learning, coupled with an awareness of the linguistic demands which they may make of their pupils, especially in a linguistically-mixed classroom. If this heightened language awareness is brought about, we see no reason why mainstream teachers should not be expected to appreciate and indeed cater for second-stage language needs, and given the necessary support, accept their responsibilities even in relation to those pupils who may enter school with little or no English.

Teacher Education

2.17 We deal at length in Chapter Nine with the role of teacher education at all levels in providing teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to teach in our multiracial, multilingual society. There are however a number of points relating specifically to language which should be drawn out here. In essence, as we have said, we would expect to see appropriate training and support being available to all teachers to enable them to cater for the linguistic needs of all their pupils. It is clear however that teachers in multilingual schools, because of the range of languages represented in the classroom, may need additional and specific help. LEAs and individual schools, within the context of a comprehensive programme of induction and in-service training, need to ensure that teachers have an increased awareness of the particular languages used by their pupils including an ability to identify which language an individual child is speaking, to identify various scripts and at the very least to be able to pronounce a child's name correctly. Teachers might also be encouraged to learn some of the basic vocabulary of the languages used by their pupils, and to understand how the structure or intonation of the languages

[page 397]

may lie behind a child's difficulty with English. We believe that such information can most effectively be imparted through school-based provision so that it can be tailored to the particular circumstances of an individual school and so that teachers can see the issues covered as directly relevant to their own classroom situation.

2.18 In addition to such specific support and guidance there is clearly a need for opportunities for further in-service training for the language specialist and LEA advisory teachers whom we have envisaged (paragraphs 2.12-2.14). We would see the key qualities of such specialist teachers as being flexibility and sensitivity. We would thus expect them to have had a wide range of experience in different teaching situations and to have acquired considerable expertise in the skills needed to help children from a range of backgrounds with their language needs. We feel therefore that in this instance classroom experience is an essential prior qualification for such work and we would not see a direct role for initial training in the preparation of such teachers. Rather, we would see their principal training needs being met through in-service work, on an LEA or regional basis, and the RSA course on 'The teaching of English as a second language in multi-cultural schools' (course details attached as Annex C) seems to us to provide an ideal basis for further course initiatives along these lines, especially in relation to the needs of second language learners. Indeed, this particular course was commended to us by a number of E2L specialists we met as being especially useful in that it is aimed jointly at both prospective language specialists and subject and class teachers wanting to learn about second language needs in order to broaden their own teaching skills. Although we see the preparation of these language specialists as an in-service responsibility we would wish to encourage initial teacher training institutions to offer a range of options for students with a particular interest in the field of language needs.

3. Mother Tongue Provision

3.1 Of all the various issues relating to language which have been raised with us, the one which has undoubtedly aroused the strongest feelings is the role of the education system in relation to the maintenance and support of the languages of ethnic minority communities, through what is generally referred to as 'mother tongue provision'. We have indeed received more evidence on this issue than on any other encompassed by our overall remit and in recent years there has been a proliferation of 'issue papers', conferences and articles devoted to this area of concern. We believe however that the issue of mother tongue provision cannot be seen in isolation from the whole question of language education and, more importantly, it must

[page 398]

be seen in the broader context of an education which responds to and meets the needs of all pupils in today's society.

Range of 'Mother Tongues'

3.2 Before considering the 'case' for mother tongue provision in its various forms, it is worthwhile recalling the diversity of languages other than English which are now spoken by pupils attending schools in this country, which we emphasised at the opening of this Chapter. The report from the Linguistic Minorities Project (LMP), already referred to, found for example that in Bradford, out of the 14,201 pupils recorded as speaking languages other than English at home, 53% spoke Punjabi, 19% spoke Urdu and 9% spoke Gujerati; in Haringey, of the 7,407 pupils speaking other languages, 34% spoke Greek, 15% spoke Turkish and 9% spoke 'Creoles' (defined as English-based and other non-French-based Creole languages); in Peterborough, of the 2,408 pupils speaking other languages, 24% spoke Punjabi and the same percentage spoke Italian. Further data from the LMP findings relating to linguistic diversity are reproduced in Annex D to this Chapter.

What is 'Mother Tongue'?

3.3 We have used the term 'mother tongue' throughout this Chapter to describe the languages of ethnic minority communities in a very particular educational context in which they have been discussed in relation to language education. It must be acknowledged however that this term has been subject to some criticism for its unnecessarily limited connotations of 'the language learned at the mother's knee'. Where communities are multilingual or speak a markedly distinct dialect, for example, Sylheti Bengali or Sicilian Italian, the languages which parents may wish their children to be taught or to be used within schools may well not be children's 'mother tongues' as such but rather standard forms of a particular language, or even different languages entirely which are regarded by the communities as of higher status. As explained in a discussion document (4) produced by the Commission for Racial Equality:

'Throughout Asian history groups of people have expressed a desire to learn another language which they see functionally more relevant than theirs. Asian children who speak Punjabi at home may well want to learn Urdu instead of Punjabi because this was the traditional language of learning for their parents. Those from the East Punjab may choose to study Hindi for religious reasons. A minority of Cantonese-speaking Chinese children may choose to learn Mandarin which is the national spoken language of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan.'

(4) 'Ethnic Minority Community Languages: A Statement'. Commission for Racial Equality. 1982.

[page 399]

In recognition of the range of languages thus under discussion, some educationists now talk of home and/or community or national languages rather than mother tongues. We have however continued to use this term here because it remains most widely used and understood.

Different Forms of Mother Tongue Provision

3.4 As with so many other of the terms used in relation to the education of ethnic minority pupils, there is considerable confusion about what is meant by 'mother tongue provision' and several essentially very different activities seem to be embraced by it. We believe it is necessary to distinguish between these different forms of provision and to look carefully at the various factors influencing them. The range of activities can we believe be seen to fall into three main 'categories' of provision:

- Bilingual Education: the structuring of a school's work to allow for the use of a pupil's mother tongue as a medium of instruction alongside English so that the child may be taught for a set part of the school day in for example Punjabi and for the rest of the time in English;

- Mother Tongue Maintenance: the development of a pupil's fluency in his or her mother tongue as an integral part of a primary school's curriculum in order to extend their existing language skills by timetabling a set number of hours each week for the teaching of for example Punjabi;

- Mother Tongue Teaching: the teaching of the languages of ethnic minority communities as part of the modern languages curriculum of secondary schools alongside established languages such as French or German.

Making the Case

3.5 The increasing concern about mother tongue provision can be seen as a major consequence of the general rise of consciousness amongst ethnic minority groups in this country. On a broader level, it has been argued that each of the forms of mother tongue provision set out above are important aspects of multi-cultural education since language is the key to both the religious and cultural heritage of ethnic minority communities and all languages should therefore be valued and maintained as part of our national linguistic resource. Mother tongue provision in all its forms has also been seen as an essential step in according ethnic minority pupils 'equality of opportunity' within our education system since it has been pointed out that an ethnic minority child from a home where English may not be spoken may at present be placed at an immediate disadvantage vis-à-vis his peers by being denied the opportunity to build on the linguistic and conceptual skills he has acquired in his early years. It is presented as a form of 'natural justice' that all children should receive their education in their own mother tongue and that since pupils whose

[page 400]

mother tongue is English have the opportunity to extend and develop their mother tongue within school in specific English lessons, those for whom English is not a first language should be given a similar opportunity to extend and develop their mother tongue. The major argument for broadening the modern languages curriculum to include ethnic minority languages is that it is sound educational practice, as well as common sense, for pupils to have the opportunity to study for and obtain a qualification in a language in which they may already have some facility.

Aims of Mother Tongue Provision

3.6 The range of specific aims which have generally been advanced in favour of mother tongue provision are summarised by the authors of the second NFER review of research as follows:

'i. To promote cognitive and social growth in the young child whose first language is not English, by the use of the mother tongue as an initial teaching medium in order to counter semi-lingualism.

ii. To increase such a pupil's confidence through the use of his mother tongue so that thereby he will gain psychological and social benefits which will enable him to improve his learning ability and increase motivation which can be applied in connection with other curriculum subjects.

iii. In accordance with the broad objectives of education such a pupil whose first language is not English has a right to have his full potential developed and this includes the development of his ability and competence in his mother tongue.

iv. To enhance the value of such a pupil's culture and the language itself as part of that culture. And by so doing to increase the status of the language, to encourage its maintenance by its speakers and to reduce social and cultural barriers between English speakers and those speaking the minority language.

v. To promote the pride of minority language speakers in their language and hence to promote their own identity through their language.

vi. To facilitate, through a maintenance of linguistic competence in the first language, communication between parents and children and relatives in other countries and hence to preserve religious and cultural traditions.

[page 401]

vii. To enrich the cultural life of the country as a whole by means of a diversity of linguistic resources and in particular through the contribution which different language speakers may make to society through their participation in social life and through their linguistic competence as demonstrated by achievements in examinations. to make a contribution to the economic life of the country through industry and commerce.'

Bullock Committee's View

3.7 Two major catalysts to the development of the mother tongue debate in this country have been the 1975 Bullock Report and the EC Directive on the Education of Children of Migrant Workers (1977). Since we feel that the actual content and intentions of both of these documents have become blurred over time, it may be helpful to recall briefly the actual terms of both. The Bullock Report, in a widely-quoted reference to mother tongue, argued that:

'No child should be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he crosses the school threshold (and) ... the school should adopt positive attitudes to its pupils' bilingualism and wherever possible should help maintain and deepen their knowledge of their mother tongues.'

Although in retrospect the Bullock Report showed considerable foresight in recognising the opportunities offered for the whole of society by the increasing linguistic diversity of Britain, it gave little guidance as to precisely what it saw schools doing in practice.

EC Directive on the Education of Children of Migrant Workers

3.8 There is clearly widespread misunderstanding as to the actual content of the 1977 EC Directive on the Education of Children of Migrant Workers as illustrated by the number of occasions on which it is mistakenly referred to as the 'Directive on Mother Tongue Teaching'. The Directive, the full text of which is reproduced at Annex E, requires that Member States should a. admit migrant workers' children from other member states to school and provide them with tuition in the language of the host country and should b. promote the teaching to these children of the mother tongue and culture of their country of origin:

'. .. with a view principally to facilitating their possible reintegration into the Member State of origin.'

Through an agreement by the Council of Ministers at the time of the Directive's adoption, the UK government accepted that the benefits of the Directive should be extended to the children of nationals of

[page 402]

non-Member States. As the DES Circular 5/81 (5) observed however:

'... the Directive and accompanying agreement do not address themselves to the position of children whose parents are UK nationals with family origins in other countries.'

- thus excluding the majority of the ethnic minority children in Britain today. This Circular also stressed that the requirement for Member States to 'promote' mother tongue and culture teaching did not accord the right to such teaching to any individual child. The context in which the EC Directive is being implemented has since been set out further in the DES 'Memorandum on Compliance' produced in 1983 (see footnote 2 above).

3.9 We believe that discussion of the provisions of the EC Directive have to a very great extent overshadowed and indeed distorted the debate about mother tongue provision. It must be recognised that the Directive was explicitly intended to ensure that the children of Migrant Workers from EEC countries received an education which would enable them to return to their countries of origin. It is surely illogical therefore to seek to extend such provisions to ethnic minority children, born and brought up in this country, the great majority of whom are unlikely to 'return home' and who neither perceive themselves nor wish to be perceived as in any sense 'transitory' citizens of this country. In order to justify the need to maintain and foster the linguistic diversity of British society today, it is surely irrelevant for the advocates of mother tongue provision to 'pray in aid' a Directive intended to meet an entirely different educational situation. The case for mother tongue provision for ethnic minority pupils in this country is indeed, as we have already indicated above, far more complex than the straightforward intention of the Directive which was simply to enable migrant workers' children to be reintegrated into their home countries - thus as the 1981 Home Affairs Committee Report (6) concluded:

'... any argument in support of (mother tongue) provision must be on the merits of the case.'

Mother tongue provision cannot be justified simply by the provisions of the EC Directive. We regret that the DES and many advocates of mother tongue provision have tended to see the arguments for such provision solely in the context of the Directive rather than as an aspect of education which merits consideration in its own right in view of the multilingual pupil population of many of our schools.

(5) 'Directive of the Council of the European Community on the Education of the Children of Migrant Workers'. DES Circular 5/81. 31 July 1981.

(6) 'Racial Disadvantage'. Fifth Report from the Home Affairs Committee, 1980/81. HC 424 I-III. HMSO.

[page 403]

Research Evidence

3.10 Advocates of mother tongue provision in all its forms have frequently argued that there is a wealth of research evidence which justifies the value of such activities. However the authors of the second NFER review of research concluded on the basis of their work that there was in fact:

'... as yet very little research evidence in the field.'

They also noted that much of the work which had been done in this field had been undertaken abroad, chiefly in the USA and Scandinavian countries, and concluded that:

'Whilst such examples of provision and bilingual programmes may indicate ways in which such work may be undertaken, their relevance to a British situation must not automatically be assumed ...'

3.11 In relation specifically to the possible benefits of bilingual education, the findings of much of the research work reviewed by the NFER could hardly be said to provide conclusive evidence as to the value of such provision - for example Mitchell (1978) (7) found that:

'... bilingual education of a pluralist character does not appear either to enhance or to depress the bilingual child's performance in the majority language, English, or in the non-language subjects. It may promote his achievement in the minority first language, particularly in relation to reading and writing skills. But there do not appear to be particularly compelling arguments. on the basis of promoting the academic achievement of the individual minority language child, for choosing between monolingual and bilingual education.'

There have been three major research projects in this country on bilingual education:

- the 1976 Council of Europe-funded project in Birmingham;

- the 1977-1981 EC/Bedfordshire pilot project (this project is referred to in greater detail in our Chapter on the Italian community later in this report); and

- the 1978-1980 DES-funded mother tongue and English teaching project in Bradford.

The findings of these projects are considered in some detail in the second NFER review of research, and the authors conclude that:

(7) 'Bilingual Education of Minority Language Groups in the English Speaking World'. Some Research Evidence. Mitchell R. University of Stirling. 1978.

[page 404]

'It would be imprudent to draw any conclusions on the basis of the three different bilingual education programmes which have been undertaken in this country as to implications for establishing the child's mother tongue prior to developing skills in a second language, English. The three projects have been conducted with three different age groups, with different objectives, at different times and in different localities, and whilst the first two were concerned with literacy, the latter project concentrated on fluency, hence they cannot be directly compared. One serious drawback to the evidence which they do supply is the lack of long-term knowledge about the influence of such programmes on various factors. not least of which is the competence of pupils iii their mother tongue and in English.'

Thus, on the strength of the NFER review, it would not seem possible for the case for any form of mother tongue provision to rest on the research evidence alone.

The Welsh Experience

3.12 Another of the arguments often put forward to support bilingual education is the experience of schools in some parts of Wales in making such provision for their pupils. The linguistic situation in Wales is however we believe far from comparable with that of the ethnic minority communities now present in our society since only one language - Welsh - is involved and this is the national language of the country and as such lies at the heart of its culture and traditions. As the then Director of the Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research recognised in his paper for a Conference on Bilingualism and British Education held in January 1976:

'The issue in Wales is clouded neither by multilingualism nor by any lack of determination of the status (cultural, political or legal) of the languages concerned ... The language policy in Wales originates from a different historical background and rests on a quite different relationship between the principal minority and majority languages, politically and legally.'

We believe similarly that the case for bilingual education for ethnic minority pupils in this country cannot be judged by the bilingual experience of some schools in Wales.

Parental Attitudes

3.13 Another major justification put forward in support of mother tongue teaching and mother tongue maintenance within mainstream schools is pressure from ethnic minority parents for such provision. The authors of the second NFER review of research draw attention to a number of surveys of the attitudes of Asian parents which in

[page 405]

the main show considerable, but by no means overwhelming or unequivocal, support for their languages being taught in mainstream schools. They note however that:

'Those research studies which do exist are all quite recent, showing that up until the emergence of the EEC Directive few had thought to ask parents what their views would be.'

Alongside the evidence of parental support for mother tongue provision, however, must be set the evidence presented in the NFER reviews and also the views expressed very clearly to us at our various meetings with parents from the whole range of ethnic minority groups that they want and indeed expect the education system to give their children above all a good command of English as rapidly as possible, and that any provision for mother tongue should in no way detract from this aim.

Community Based Provision

3.14 Above all, however, the degree of community support for mother tongue provision is claimed to be manifested by the existence of widespread thriving community based language classes. On many occasions it has also been claimed that the only reason why ethnic minority community languages have survived so long in the absence of provision in mainstream schools is the very existence of such community based provision. It may be worth noting however that in many cases the communities would see their own classes continuing in existence even were mother tongue provision in all its forms to be incorporated within mainstream schools, because of the religious and cultural implications of certain languages, and as a positive form of self help which provides a valuable focal point particularly for isolated minority communities. In this connection we have received a considerable amount of evidence from the organisers of community based provision regarding the widely varying degrees of support offered to them by LEAs in different parts of the country, with pleas for a uniformity of approach. The problems faced by the providers of existing community based provision, highlighted in evidence to us from community representatives, can be summarised as follows:

- inadequate and inappropriate accommodation e.g. in private houses or religious meeting places;

- 'teachers' who may in fact not be trained teachers and may not be experienced in using the teaching methods, teaching styles and patterns of discipline of mainstream schools;

- inadequate and inappropriate teaching materials, textbooks and resources generally;

[page 406]

- the timing of such provision - in the evenings and at weekends;

- wide variation in the quality of the provision made; and

- the low status of the provision in the eyes of many people including even the pupils attending.

Our View

3.15 We are conscious that we will be expected to declare ourselves as either 'for' or 'against' mother tongue. We are without doubt 'for' mother tongue in the sense that we regard the linguistic diversity of Britain today as a positive asset in just the same way as everyone welcomes the many dialects and two indigenous languages (Welsh and Gaelic) of the different regions of the United Kingdom. We are also 'for' mother tongue in that we see all schools having a role in imparting a broader understanding of our multilingual society to all pupils, and 'for' mother tongue in the value which we attach to fostering the linguistic, religious and cultural identities of ethnic minority communities. By like token we applaud the way in which schools in our three national regions - Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland - have helped preserve a national identity within a United Kingdom. Where we differ from the view taken by some advocates of mother tongue provision is in the role which we see for mainstream schools in the maintenance and use of ethnic minority community languages. We find we cannot support the arguments put forward for the introduction of programmes of bilingual education in maintained schools in this country. Similarly we would regard mother tongue maintenance, although an important educational function, as best achieved within the ethnic minority communities themselves rather than within mainstream schools, but with considerable support from and liaison with the latter. We are however wholeheartedly in favour of the teaching of ethnic minority community languages, within the languages curriculum of maintained secondary schools, open to all pupils whether ethnic minority or ethnic majority. We now expand on these broad conclusions.

Concern About 'Separate' Provision

3.16 It is clear that both bilingual education and mother tongue maintenance can only be of relevance to mother tongue speakers of languages other than English, i.e. to pupils from certain ethnic minority groups. Where such provision has been made therefore it has inevitably meant that ethnic minority pupils have had to be separated from their peers for 'special' teaching. As we have stressed throughout this report, we are opposed in principle to the withdrawal of ethnic minority pupils as an identifiable group and to the concept of 'separate' provision. We cannot accept that such provision can in any sense, as has been suggested, reduce social and cultural barriers between English speakers and ethnic minority pupils. On the contrary, we believe that any form of separate provision catering

[page 407]

exclusively for ethnic minority pupils, serves to establish and confirm social divisions between groups of pupils. It also leaves the ethnic majority pupils' education impoverished and monolingual and the negative perceptions of the 'strangeness' of ethnic minority groups, which lie at the roots of racism, unaffected. Linguistic barriers between groups can we believe only be broken down effectively by a programme of general language awareness for all pupils such as we propose later in this Chapter. Neither can we accept the argument that for ethnic minority pupils to be taught through the medium of their mother tongue accords them equality of opportunity in this society. On the contrary, the key to equality of opportunity, to academic success and, more broadly, to participation on equal terms as a full member of society, is good command of English and the emphasis must therefore we feel be on the learning of English. We find the research evidence that the learning of English can be assisted by bilingual education or mother tongue maintenance, unconvincing, since in many instances the most that can be claimed from particular projects is that the child's learning of English is not impaired and may in some respects be enhanced. We have also noted with interest the American experience which has led to a current move there away from some of the programmes of bilingual education which had previously been established. Where the languages which parents may wish to see being taught are not their children's 'mother tongues' as such, but possibly entirely different languages we would also see the linguistic argument of enhanced development of the 'first language' as a basis for learning English, as invalid.

Bilingual Resource

3.17 We accept that, for any child, starting school represents a tremendous upheaval, even where the linguistic, social and cultural context closely mirrors that of his or her home. For a child with little or no English, and with a different cultural frame of reference, the experience can clearly be even more traumatic. It has been suggested that mother tongue provision can help to ameliorate the difficulties facing non-English speaking pupils entering school for the first time. It must however be recognised we believe that such provision can at best serve only to delay rather than overcome the trauma for these pupils of entering an English speaking environment. We believe however that a particularly important role can be played within primary schools, and in particular in nursery classes, by what we would term a 'bilingual resource' to help with the transitional needs of a non-English speaking child starting school. We would see such a resource providing a degree of continuity between the home and school environment by offering psychological and social support for the child, as well as being able to explain simple educational concepts in a child's mother tongue, if the need arises, but always working within the mainstream classroom situation and alongside the class

[page 408]

teacher. We would in no way however see such a situation as meaning that a child's mother tongue should be used as a general medium of instruction or should form a structured part of the curriculum as has traditionally been envisaged in programmes of bilingual education and mother tongue maintenance. Such a role may be undertaken by a bilingual teacher, non-teaching assistant or nursery nurse already on the staff of the school, or even by a parent, or possibly by fifth or sixth-formers from local secondary schools as part of their child care courses or community service experience. It should not be assumed however that the bilingual 'resource' will as a matter of course relate to pupils from the same linguistic, cultural or ethnic groups when their backgrounds may be entirely different; nor should they be seen as 'catering' just for the ethnic minority pupils but rather as an enrichment of the education of all pupils.

Enhanced Support for Community Based Provision

3.18 As far as provision for mother tongue maintenance is concerned we do not believe mainstream schools should seek to assume the role of the community providers for maintaining ethnic minority community languages. Languages are dynamic and are continually being modified and developed by the users according to context and environment. They thrive by being used, not merely taught. If a language is truly the mother tongue of a community and is the language needed for parent/child interaction and for discussions within the immediate and extended family, or for access to the religious and cultural heritage of the community, then we believe it will survive and flourish regardless of the provision made for its teaching and/or usage within mainstream schools. Since the education system does however we believe have a role to play in assisting communities to retain their linguistic heritages, we would see this broad aim best being achieved through the establishment of comprehensive programmes of support by LEAs for existing provision for language maintenance by the 'language communities' concerned. In order to overcome some of the difficulties faced by the community providers over matters such as accommodation and teaching resources, we would like to see far more community language classes being held on mainstream school premises. We would like to see LEAs adopting a more uniform approach to this issue in making school premises available free of charge and encouraging community providers to use them. By thus bringing the community language classes physically within the mainstream school this will inevitably promote greater interest and understanding, on the part of mainstream teachers, of the activities taking place. We would also hope to see the 'community teachers' becoming more involved in mainstream school activities, for example, being able to discuss the progress of a particular child with his or her class teacher. At present the very marked isolation of these community based language classes

[page 409]

from mainstream schools is illustrated by the fact that most mainstream teachers to whom we spoke, apart from commenting adversely on the provision made, showed a remarkable lack of knowledge about this part of their pupils' overall education. We would therefore like to see the two providers of a child's education - the community and the school - being brought closer together. Forging this closer link will be made all the easier, and the communities' concerns about the timing of some existing language classes will be overcome, if the classes themselves take place either at lunchtime or immediately at the end of the school day. We would also see LEAs' financial responsibilities for community based classes extending to making grants available to the providers for the purchase of books and the development of teaching materials. Similarly, we would like to see advice and support being offered by LEA advisory services for the community teachers on teaching methods, teaching styles and resources, and possibly even the provision of short ad hoc in-service style courses for the teachers, to meet some of the concern felt by the community about the extent to which their teachers are able to provide for this important aspect of their children's education. In order to reassure LEAs that the best possible use is being made of the resources to be provided for these classes, and also to allay the concerns voiced by the community about the variable 'quality' of provision, we would expect LEA advisory staff to visit the classes on a regular basis to offer guidance on the work being done.

Mother Tongue Teaching

3.19 The area of mother tongue provision where we believe the greatest shift in attitude is needed is in relation to what we have termed mother tongue teaching and the artificial distinction which has been drawn in secondary schools between what are generally termed modern or foreign languages and ethnic minority community languages. The educational value to an individual of learning a language other than his own is an indisputable component of a full and balanced education. However, the pre-eminence of French and German as the languages offered by schools, whilst perhaps having originally been based on sound educational reasons seems, in today's interdependent world and within our own multilingual environment, somewhat harder to explain and defend. Within the context of 'Education for All', we believe it is entirely right for a white English speaking pupil to study an ethnic minority community language as a valid and integral part of his education. For a bilingual pupil, we believe it is only reasonable to expect that he should be able to study for a qualification in a language in which he already has some facility. We believe therefore that the teaching of ethnic minority community languages should form an integral part of the curriculum in secondary schools. Similarly, at LEA level, we would expect to see modern languages advisers having responsibility for the whole range of

[page 410]

languages offered, including the languages of ethnic minority communities, rather than, as is usually the case at present, provision for the latter, if recognised at all, falling within the remit of the multi-cultural adviser or the E2L specialist. We are convinced that a facility, or even a qualification, in a community language should be seen as providing any young person with a skill of direct relevance to work in areas of ethnic minority settlement in fields such as social services, nursing and education, where dealing with people is so important. We would therefore expect to see schools and the careers service emphasising the value of languages in such careers, and employers, particularly local authorities, seeing language skills as one of the criteria to be used when making appointments in these fields.

Attitudes of Pupils

3.20 It is interesting to note that in the schools we visited where ethnic minority community languages were already part of the curriculum, a number of the language speakers had in fact not chosen to study them. In some cases this was clearly because the languages were timetabled against other subjects which the pupils felt were more relevant to their future careers but in one LEA it was simply because the languages had been added to the school curriculum, almost as an afterthought, after the timetables had already been drawn up. To counter this, we would expect to see community languages being built into the school timetable from the start as an integral part of the curriculum. In addition it is clear that some pupils may have been influenced by the albeit sub-conscious negative view of their languages which we still found to be present in these schools which meant they found it difficult to see them as 'proper' subjects for study. Of greater significance however may be the attitude of those pupils who seemed to resist the religious and cultural overtones of studying their languages in school which to them seemed to unnecessarily prescribe their future cultural frame of reference. We found this latter reaction particularly interesting since we ourselves would never wish to see an ethnic minority pupil being compelled, whether by the school or his parents, to study his language; simply that the opportunity for him to do so should be there. We recognise of course that for a school to offer these languages there would need to be a viable class size, as with any other subject, but we would like to see schools regularly assessing and reassessing the demand for such provision and, where demand is only limited, considering offering the subjects in conjunction with other schools, on a consortium basis. It is important that schools should not assume that the demand for such provision will come solely from 'mother tongue' speakers of the languages. We would hope to see a growing number of other pupils, and perhaps more importantly their parents and teachers, seeing these languages as realistic options for them. We have therefore

[page 411]

been delighted to find on our visits a number of instances of 'white' as well as West Indian pupils studying Asian languages.

Teachers of Ethnic Minority Community Languages

3.21 Since we are looking for ethnic minority community languages to be given their rightful status and for an acceptance of their validity both as media of communication and as subjects for academic study of relevance to all pupils in multilingual Britain, it is vital that the teachers employed to teach them must be demonstrably 'good at their jobs' to merit equal status with other subject specialists. We have been concerned, from the evidence which we have received, and from our own visits, about the low status often accorded to teachers of ethnic minority languages at present, which can be seen as a subconscious extension of the negative view which still persists in schools of ethnic minority groups and the languages they speak. We would challenge the assumption often made by schools that any teacher who happens to be bilingual or multilingual can 'automatically' teach his language or languages. Language teaching is a highly specialised area of work which requires particular skills, and just as an English speaking science teacher would not be expected to teach English to O Level standard neither should a Punjabi speaking teacher of maths necessarily be expected to be able to teach Punjabi at this level. We have been concerned about the limited teaching ability of some of the teachers of ethnic minority languages whom we have met. Indeed some ethnic minority pupils ascribed their reluctance to study the languages to the 'quality' of the teachers. We regard it as important therefore that any teacher employed to teach an ethnic minority language in a mainstream school must hold recognised qualifications in the language concerned, must have received professional training in this country in the techniques needed to teach a language and must be fully proficient in English. Only thus can he or she hope to convince their teaching colleagues and pupils and indeed parents from all groups, of the validity of the subject. At present there are clearly few people, even including many existing teachers of ethnic minority community languages, who, without a good deal of support and preparation could meet these criteria. Remedying this situation represents a tremendous challenge to those responsible for training teachers but one which, we believe, must be met. The time has come for the balance to be redressed to a point where it should be quite possible and acceptable for a specialist in ethnic minority languages to progress to become the head of a secondary school modern languages department or even ultimately a modern languages adviser.

[page 412]

Survey of Capacity for Training Teachers of Community Languages

3.22 In an attempt to investigate the extent to which teacher training institutions were responding to this challenge we commissioned a research team based at the University of Nottingham School of Education to undertake a survey of the existing and potential capacity of institutions for preparing students to teach ethnic minority community languages in schools. The results of this survey (8), which are summarised in Annex F, were on the whole rather disappointing if not unexpected. The researchers found that:

'PGCE courses in modern languages cater overwhelmingly for graduates in French and German ... Nowhere in England and Wales can a graduate in ethnic minority community languages ... obtain an appropriate training for teaching ... The BEd situation is even weaker, and seems bound to deteriorate as the degree becomes predominantly a primary teaching qualification.'

Looking to the future however the situation was found to be slightly more encouraging. The researchers found evidence of at least some interest or potential expertise in the teaching of ethnic minority community languages spread across some thirty-seven institutions of which eight were significantly ahead of the rest. The task of ensuring that schools are able to recruit teachers of ethnic minority community languages of the quality and indeed the quantity they clearly need is of vital importance. We would urge the government therefore to respond to the situation by taking measures to ensure that potential teachers of these languages receive the degree of training, support and recognition they are entitled to expect throughout their careers. A useful first step in this direction would, we feel, be for the DES to commission a further in-depth study of the eight teacher training institutions considered by the Nottingham researchers to be 'potential centres of growth' in order to identify which have the greatest capacity for development in terms of both initial and inservice provision and to detail the additional resources which would be required to fully realise their present potential. (See paragraph 6(iii) of Annex F.)

Resources and Examinations

3.23 If ethnic minority community languages are to become part of the mainstream languages curriculum, appropriate teaching materials and general resources must be developed. At present, where the languages are being studied, the textbooks and readers being used have more often than not been produced abroad, often for use in teaching young children their own languages - thus the cultural

(8) 'Training Teachers of Ethnic Minority Community Languages', a Research Project by Professor M Craft and Dr M Atkins of the University of Nottingham School of Education. 1983.

[page 413]

and social background and the target age group makes them entirely inappropriate to the needs of secondary age pupils born and brought up in this country. We would therefore like to see educational publishers beginning to produce appropriate teaching materials as part of their modern languages output, not only for use in mainstream schools but also in community language classes to bring the curriculum content there closer to that of other language provision. The production of teaching materials is of course closely bound up with examination provision. Those existing examining boards who offer examinations in ethnic minority languages - and we would like to see a considerable expansion of the provision made in public examinations at all levels - do not at present go beyond simply setting the paper as such, and do not prescribe the syllabus to be followed. We would like to see however greater consideration being given to syllabus content in order to bring the provision for these languages in line with other subjects.

4. Language Across the Curriculum

Bullock Report

4.1 We have argued here for a greater awareness of the language needs of all children and for increased recognition to be given by schools to the positive aspects of the multilingual nature of society today. We have also stressed that we would see all teachers having some responsibility for meeting the linguistic needs of all their pupils, including those for whom English is not a first language. This view that teachers must take their responsibilities in respect of the linguistic development of their pupils more seriously is not of course new, and indeed this was one of the major messages of the Bullock Report which inter alia advocated the development of policies for 'language across the curriculum' in all schools, in the following terms:

'In the primary school the individual teacher is in a position to devise a language policy across the various aspects of the curriculum, but there remains the need for a general school policy to give expression to the aim and ensure consistency throughout the years of primary schooling. In the secondary school, all subject teachers need to be aware of

i. the linguistic processes by which their pupils acquire information and understanding, and the implications for the teacher's own use of language;

ii. the reading demands of their own subjects, and ways in which the pupils can be helped to meet them.'

To bring about this understanding every secondary school should develop a policy for language across the curriculum. The responsibility for this policy should be embodied in the organisational structure of the school.'

[page 414]

Despite the proliferation of both LEA and school-based in-service courses on the concept of 'language across the curriculum' and the number of relevant publications, few schools have been able to translate this vision into effective practice - as the 1979 Secondary Survey (9) found:

'... the policies for language across the curriculum in secondary schools recommended by the Bullock Report are difficult to achieve, for a variety of reasons; it may be, indeed, that the phrase itself has not been widely enough understood or that it is not forceful enough to convey the notion of the overall responsibility of all teachers for the development of language essential to learning. In a great majority of schools ... no moves of any significance towards language policies have taken place.'

A further discussion paper (10) produced by HMI in June 1982 found a very similar situation and the evidence which we ourselves have received appears to confirm this general lack of progress with the implementation of the Bullock Committee's recommendations in this field.

Ethnic Minority Dimension