[page 66]

7 A new partnership

Our priority is standards, not structures. But we need a new and clearer framework in which all the partners understand their roles and can work effectively together towards the common goal of raising standards.

Community, aided and foundation schools

1 The focus of debate in recent years has been too much on school structure, too little on standards. The development of Grant Maintained schools has led to concerns about fairness and co-operation between schools. In some areas there is a lack of clarity about who is accountable for what.

2 We need a new framework which strikes a better balance between fairness, co-operation, diversity between schools, and the power of schools to decide their own affairs. It must allow all good schools to flourish, leaving in place whatever is already working well, while providing better support for those schools that need to improve. We will be consulting later on a technical document about the detailed arrangements.

3 The underlying principles of the new framework are:

- Schools are responsible for their own standards. They should continuously and actively seek to improve their performance so that every child can succeed.

- There is value in encouraging diversity by allowing schools to develop a particular identity, character and expertise.

[page 67]

- The central part which the churches and other foundations have long played in providing schools should be recognised, safeguarding the ethos of voluntary schools.

- Schools should be free to make as many decisions as practical for themselves, in particular on internal management, resource allocation and day-to-day operation.

- But that freedom must be accompanied by accountability to parents, the local community, and the wider public for what they achieve.

- There will be no question of attaching unfair privileges to a particular category of school in funding, admissions arrangements or planning school places. All schools, and all categories of school, must be treated fairly.

- The role of LEAs is not to control schools, but to challenge all schools to improve and support those which need help to raise standards.

- To avoid distraction and disruption for schools, the changes made to establish the new framework should be kept to the essential minimum.

Question: Are these principles for designing the new schools framework the right ones?

4 The June 1995 policy statement, Diversity and Excellence, set out proposals for three categories of schools - community, aided and foundation. These categories will incorporate all LEA and GM schools.

5 Community schools will be similar to the existing county schools (which account for some 14,000 out of the 22,000 primary and secondary schools in England). The LEA will continue to employ their staff and own their premises. We intend to include more parent governors on governing bodies, but otherwise county schools which become community schools will remain largely unchanged.

6 Both aided schools and foundation schools will employ their staff and own their premises, broadly as voluntary aided and GM schools do now. The main difference between aided and foundation schools will be that aided schools will contribute at least 15% towards their capital spending (as existing voluntary aided schools do) and will accordingly have a majority of "foundation governors" (see paragraph 7 below). Like the present voluntary controlled schools, foundation schools will not be required to contribute anything towards capital costs, so "foundation governors" will not have an absolute majority. Foundation schools will have no more than two LEA governors.

7 Existing voluntary schools in the GM and LEA sectors already have foundations, separate from the governing body, which appoint "foundation governors" and hold the school's premises in trust. These will continue. We are considering the role of new foundations that might be required for schools which become aided or foundation schools. We are also considering the implications for controlled schools, in cases where they move to foundation status, of becoming the employers of their staff; we are mindful of the need for flexibility.

8 Schools should be able to choose which status will best suit their character and aspirations. But we do not want the mechanisms for choosing to distract attention from the main purpose of raising standards and we assume that the great majority of schools will wish to choose a category which is as close as possible to their existing status. For example, because of their special relationship with their church or other foundation, we expect voluntary aided schools will generally wish to choose aided status.

9 The Government therefore proposes to frame the necessary legislation in terms of a set of assumptions that schools in an existing category will generally move to a specified new category, unless the governing body chooses otherwise. Where the governing body did wish

[page 68]

to choose a different category, or a significant proportion of parents were unhappy with the proposed new status, a ballot of parents would provide a mechanism for testing whether parents agreed with that choice. Where there was disagreement which could not be resolved, the final decision would be referred to the Secretary of State. We will be consulting in detail on the procedures for schools to choose their new status, including the place of ballots.

10 The pattern of ownership of school premises is complex. In broad terms, the LEA owns the premises and assets of county schools, and that will continue for community schools. In voluntary schools, the foundation holds the main premises, but the LEA generally owns playing fields and subsidiary assets; while GM school governing bodies (with their foundations in the case of former voluntary schools) own all the school's assets. Trying to achieve complete consistency of ownership for aided and foundation schools would create too much turbulence. So we intend to adopt the guiding principle that schools should continue to hold what they have now We shall ensure that the Secretary of State can apply proper safeguards to the disposal of assets bought with public funds.

11 There are 1,200 maintained special schools in England. These playa valued part in providing for children with severe SEN. In the Green Paper announced in Chapter 3 we shall be seeking views on the way to develop these schools. Because of the need to protect highly specialised provision, there has always been closer statutory control of special schools than their mainstream counterparts. An individual special school may contribute to vital provision at regional, and sometimes national, level. We shall explore ways of strengthening the planning of this essential provision. The need for such planning is likely to imply that all maintained special schools, including the small number of GM special schools, should become community special schools.

School governors

12 Governors have a special role as partners in the school service: they provide a vital link between the school and the community. We shall strengthen that link by increasing the number of parent governors.

13 The purpose of governing bodies is to help provide the best possible education for its pupils. To do this effectively they should have a strategic view of their main function - which is to help raise standards - and clear arrangements for monitoring progress against targets. They need to challenge the expectations of the headteacher and staff as well as providing support. To achieve a proper working partnership, governing bodies and heads have to recognise and respect each other's roles and responsibilities. Headteachers must give governors the information they need to help the school to raise its standards. Governors must give headteachers the freedom to manage and deliver agreed policies.

14 We do not think it right to legislate for all the details of the relationship between headteachers and governors. But we welcome the Guidance on Good Governance produced by a working group of governor, headteacher and other national associations This is precisely the type of partnership we want to see.

15 Governors bear a heavy workload and we will seek to minimise these burdens in introducing the new community, aided and foundation framework.

16 We have set out in Chapter 3 the support LEAs should provide to governing bodies to help them succeed. In addition, we shall encourage LEAs to set up independent governors' forums, to make full use of existing governor associations and to involve governors in the development of policy. LEAs will be asked to cover their intentions for consultation, information and other support and training for governors in their Education Development

[page 69]

Plans. We shall issue guidance on how governors' training needs can be met, drawing on the best of existing LEA practice.

| Case Study: Northicote School, Wolverhampton

Northicote School is an 11-18 comprehensive with 500 pupils. It was the first school in the country to be declared failing, and the first to come off special measures. 30% of pupils are entitled to free school meals. 70% have special needs. The OFSTED report listed 12 main areas in which the school was failing its pupils. They ranged from poor standards of achievement to truancy and vandalism. Some of the school's accommodation was so poor that there had been rumours of closure for several years.

The governors had been grappling with poor accommodation and financial problems but had little idea standards were so low. Stirred by the inspection, they quickly acknowledged their responsibilities. Although governors share a heavier workload than before, they see that they have a real job to do in delivering school improvement. Support from the LEA, including a major refurbishment, has improved the learning environment, encouraged a sense of pride, and improved professional development.

Governors quickly brought parents on board. Sporting initiatives and a family literacy project encouraged parents into school. Local businesses provided some new governors. Teaching quality and management have improved because of strong leadership and intensive training. The governors and head refused to duck staff underperformance. Monitoring and target setting are routine and no longer seen as a threat. A culture of achievement applies to staff and pupils. |

The role of LEAs

17 The role of LEAs has changed dramatically over the past decade. It is no longer focused on control, but on supporting largely self-determining schools. LEAs must earn their place in the new partnership, by showing that they can add real value. Chapter 3 sets out the ways in which LEAs should help to raise standards and ways in which the performance of LEAs themselves can be improved.

18 The leadership function of an LEA is not based on control and direction. It is about winning the trust and respect of schools and championing the value of education in its community, for adults as well as children.

19 If we are to hold LEAs to account for their performance, we owe it to them to ensure that they have a clear job description and the tools to do that job. Our view of the administrative role of LEAs was set out in Diversity and Excellence. Their administrative functions properly include activities such as: organising education outside school; planning the supply of school places; setting overall school budgets; organising services to support individual pupils, such as transport and welfare services; and supplying services such as personnel and finance advice for schools to buy. LEAs should carry out these functions to a high standard for all state schools

Question: Does the administrative role of the LEA set out here include the right functions?

Finance

20 The recurrent funding arrangements must support the respective roles of schools and LEAs. LEAs must be able to retain centrally the funds needed to carry out their responsibilities. At the same time, we recognise the benefits which Local Management of Schools (LMS) has

[page 70]

brought. Schools have thrived on the opportunities offered by delegation of budgets and managerial responsibilities. They should be able to decide, wherever possible, what services they want to buy, and from whom they want to buy them.

21 The Government will require LEAs to delegate more of their budgets to heads and governors. LEAs should also minimise the proportion of their budget that is spent on central administration. We want to develop a school funding system which does not discriminate unfairly between schools or pupils. LMS will be the means through which all schools are funded - community, aided, foundation; mainstream and special. But any changes to the present arrangements must recognise the different starting points for different schools. We must avoid unnecessary disruption to the education of pupils. This will govern our decisions as we develop a new LMS framework.

22 The legislation required to change the coverage of LMS will also provide statutory backing for key national policies, particularly on delegation of budgets from LEAs to schools and on local distribution of funds to schools using objective formulae. The legislation will also cover consultation and exchange of information between schools and LEAs. Our aim will be to make school budget setting as simple, transparent and fair as possible. There will be a clear separation between the funds for LEA functions which need to be retained centrally and those for school functions which should be delegated.

23 New requirements for delegating budgets and rules on formula distribution can be expressed in various ways. Before we reach conclusions on what the regulations should say, we will carry out detailed consultations. We also need to review the way funding is allocated between different parts of the country, so that schools' budgets fairly reflect their circumstances - including both those things which all schools have in common (such as teaching the National Curriculum) and those things which differentiate them (such as the pressures of providing high quality education in disadvantaged areas).

24 The principles of fair funding and avoiding unnecessary disruption will also govern our work on funding for GM schools in 1998-99. We will consult on the details of this.

25 Continued under-investment in school buildings has left the nation a difficult legacy. Public assets have been allowed to deteriorate to the point where the state of the fabric of our schools has a detrimental effect on the teaching and learning that goes on within them; at the same time a significant surplus of school places has been maintained at unnecessary additional cost. We must address these problems, but capital resources are always in short supply. We shall therefore be pursuing all possible ways of levering in further funding from a variety of sources to improve the condition of the schools estate and make better use of the funds available. In particular we shall be developing the use of Public/Private Partnerships, in which families of schools and consortia of contractors can address the inherited problems of the backlog of repairs and maintenance, where possible involving wider regeneration projects. This will make it easier for all schools to attract private and community support on a consistent basis.

Organisation of school places

26 At present most proposals for making significant changes to schools organisation, such as opening, closing or expanding a school, need approval from the Secretary of State. The arrangements were originally designed to reconcile potentially conflicting interests and allow the government to influence the developing pattern of school places. But they have become too centralised. They involve the government in detailed consideration of matters best sorted out locally. The Audit Commission report Trading Places, published in December 1996, drew attention to some of the tensions within the present arrangements.

[page 71]

27 We want to move to more devolved decision-making. One option would be to bring together schools, the Churches, the LEA and other interests to draw up a local structure plan for school places. The plans would reflect demographic trends and other strategic factors affecting the future need for places. If the plan met with objections locally, it could be put to an independent inquiry. Proposals about individual schools could also be considered by local interests in the same way.

Question: What are the best arrangements for a local partnership in planning the organisation of school places?

School admissions

28 We want as many parents as possible to be able to send their children to their preferred school. But where demand exceeds supply and one school is more popular than another, some parents will be disappointed. A recent survey by the Audit Commission (in their report mentioned above) estimated that nearly one parent in five did not get a place for their child at their genuine first preference school. Yet the Commission also drew attention to the level of unfilled school places; currently over 800.000 in England.

29 Parents must have the information they need to see what different schools can offer and to assess their choices realistically. Where a school is over-subscribed, there must be clear and fair criteria for deciding applications. Church schools may reasonably carry out interviews to assess religious or denominational commitment. Places should not otherwise be offered on the basis of an interview with the pupil or parent.

30 At present LEAs are 'admission authorities' for county and controlled schools but governing bodies play that role in GM, VOluntary-aided and special agreement schools. This can lead to difficulties, and uncertainty for parents. We will therefore expect to see the development of local forums of headteachers and governors from community, aided and foundation schools, to share information about their schools' admissions arrangements, with administrative support from LEAs. We will expect the forums to develop helpful and timely information for parents and common timetables for applications for their local area. Guidance on the establishment and operation of such forums will be provided by the DfEE.

31 National guidelines on admissions policies will be set by the Secretary of State. In our new partnership, aided and foundation schools will be able to put forward policies in the light of the guidelines. They will be expected to discuss them with the LEA which will also have responsibility for the admissions policy of community schools. Where agreement cannot be reached, there will be access to an independent adjudicator. We believe that the vast majority of disputes will be resolved through this mechanism.

32 We also propose to ensure that appeals by individual parents against non-admission will be heard by an independent appeals panel.

33 Under the previous government's June 1996 guidance, schools are able to select up to 15% of their pupils by general academic ability without the need for statutory proposals. This was heavily opposed during consultation on that guidance, with only 15 out of 1500 consultees speaking out in favour. Some schools have published statutory proposals and introduced more than 15% selection. The use of partial selection, though limited, has led to controversy and caused parents concern in areas such as Bromley and Hertfordshire. We shall therefore rule out for the future partial selection by academic ability; the adjudicator will be able to end this practice where it currently exists. We will ensure that schools with a specialism will continue to be able to give priority to children who demonstrate the relevant aptitude, as long as that is not misused to select on the basis of general academic ability. We expect

[page 72]

those involved in deciding admissions arrangements for September 1998 to have regard to the principles and policies set out here.

34 There are 163 grammar schools in England. We have made our position on grammar schools clear over the last two years. There will be no going back to the 11-plus. However, we recognise that, where grammar schools exist, local parents have an interest in decisions on whether their selective admissions arrangements should continue. Changes in the admissions policies of grammar schools will be decided by local parents, and not by LEAs. We have previously indicated the mechanisms which might be used to achieve this, and will consult further on the way in which our balanced approach can be carried through.

Questions:

What are the main characteristics of effective locally co-ordinated admission arrangements, and how can they best be encouraged?

How can we ensure that as many parents as possible have a place for their child at their preferred school, without considerable extra expense and adding to the number of unfilled school places overall?

Independent schools

35 The new partnership should embrace independent as well as state schools. The best independent schools can offer children extensive facilities in sport, music and the other arts; specialist teaching in subjects such as the less common foreign languages; nationally important provision for certain types of special educational needs; and a variety of patterns of boarding provision. The educational apartheid created by the public/private divide diminishes the whole education system.

36 The music and ballet scheme and the choir schools schemes are national partnerships which already give opportunities to talented children from all over the country. They could be models for specialist provision at national or regional level to foster talent in different fields - such as the other arts, sport and languages.

37 Less formally, independent schools could, as an expression of their charitable role, offer opportunities for many more children by sharing their activities and facilities with the local community. Afternoon homework centres, Saturday enrichment classes, holiday arts, sports and language courses are examples already in place in Dulwich, Birmingham and elsewhere. Through new local partnerships these could be made available more widely, and extended into other kinds of activities. For instance, they could include the use of flexible boarding at independent or state schools for children needing that environment at a particular time in their lives. We will consult LEAs, independent schools, specialist organisations and others about ways of developing these opportunities.

[page 73]

Summary

This chapter sets out a new partnership for raising standards. By 2002 there will be:

- a new framework of foundation, community and aided schools, allowing all good schools to flourish and keeping in place whatever is already working well, while giving better support for those schools that need to improve;

- clearly understood roles for school governors and for LEAs so they can contribute positively to raising standards;

- fair and transparent systems for calculating school budgets, which allow schools as much freedom as

| possible to decide how to spend their budgets;

- more local decision making about plans to open new schools or to change the size or character of existing schools;

- fairer ways of offering school places to pupils;

- no more partial selection by general academic ability; and

- a more positive contribution from independent schools to our goal of raising standards for all children, with improved partnership and links with schools and local communities.

|

Consultation

| We will publish for consultation later this summer details of how the new framework will work, paving the way for legislation in the Autumn. That will cover in particular consultation on: the foundation, community and aided structure; the role of LEAs; revising the rules for Local Management of Schools; devolving decision making on the supply of school places; and procedures for deciding school admission arrangements. We have also established a consultative group representing the main national organisations to help us work up the detail. We will consult separately about ways of improving partnership between the state and independent sectors.

Meanwhile, we welcome comments on the proposed framework, in particular:

- Are the principles set out in paragraph 3 for designing the new framework of

| foundation, community and aided schools the right ones?

- Does the role of LEAs described in paragraphs 17-19 include the right functions?

- What are the best arrangements for a local partnership in planning the organisation of schools places?

- What are the main characteristics of effective locally co-ordinated admission arrangements, and how can they best be encouraged?

- How can we ensure that as many parents as possible have a place for their child at their preferred school, without considerable extra expense and adding to the number of unfilled school places overall?

|

[page 74]

Consultation - how to respond

[Note For obvious reasons, the contact details shown below are no longer valid.]

This White Paper sets out what we aim to achieve over the next five years to raise standards in education. We want everyone involved in education to consider and discuss these proposals. A full and open debate is vital if everyone is to play their part in raising standards.

We will be undertaking a full programme of regional and local consultation. Copies of this White Paper are being sent to all schools, LEAs and national bodies. A summary version is available free of charge from the freephone number given below. We would urge all schools to discuss these proposals with parents and other partners.

We welcome comments on all the areas covered by the White Paper. The questions on which we would particularly welcome views that are set out in the text are also brought together here. Under the code of practice on open government, any responses will be made available to the public on request, unless respondents indicate that they wish their response to remain confidential.

Written or taped comments can be sent to: Stuart Miller, DfEE, Excellence in schools, Room 4.63, Sanctuary Buildings, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BT or by fax 0171-925 6425.

This White Paper and its summary version are available on the Internet. The address is: http://www.open.gov.uk/dfee/dfeehome.htm. Comments can be e-mailed to: schools@numbers.co.uk.

The White Paper is also available in Braille and on audio cassette.

A summary version of this White Paper is available free of charge by calling 0800 99 66 00 (it is also available in Bengali, Gujerati, Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu and Chinese, in Braille and on audio cassette). The summary is primarily aimed at parents and contains a form to record their comments. The questionnaire form can be sent Freepost to DfEE, Excellence in schools, Freepost, 13th Floor, Crown House, Linton Road, Barking, Essex IG11 8BR.

More information about this and other consultation exercises that are described in this White Paper is available from the special Excellence in schools helpline: 0645 123 001 (this line is open 9am-5pm Monday - Friday until 7 October).

The consultation period closes on 7 October 1997.

[page 75]

Chapter 1 does not contain any questions for consultation

Chapter 2: A sound beginning (page 15)

- What should early excellence centres do for children, parents and the local community?

- What information from the assessments that are carried out when children start school would parents find most helpful?

- What should be done in the National Year of Reading in 1998/99 to help raise standards of literacy?

- What effective ideas for teaching, and the involvement of parents and the community, would you wish to see as part of the numeracy strategy?

Additional and more detailed technical consultation is being undertaken on:

- Early-years development forums.

- Smaller primary classes.

- The numeracy strategy.

Chapter 3: Standards and accountability (page 24)

- What more can be done to ensure that clear information on pupil performance gets through to schools, LEAs, parents and the local community?

- How can schools and LEAs ensure that they use the target-setting process most effectively to improve performance?

- How much of an LEA's work should be covered in its Education Development Plan?

- What more support do governors need from their LEAs?

- How can the proposed early warning system strike the best balance between the respective duties of the school and the LEA to raise standards?

- In what ways can the OFSTED inspection system be further refined and improved?

- What more can and should the Department itself do to support and challenge its partners in education?

Additional consultation is being undertaken on:

- the content and preparation of Education Development Plans; and

- ways of monitoring ethnic minority pupils' performance and developing action plans to tackle underperformance.

Chapter 4: Modernising the comprehensive principle (page 37)

- How can schools be encouraged to use more flexible and successful approaches to the grouping of pupils?

- What should be the main characteristics of Education Action Zones if they are to achieve the objective of motivating young people in tough inner city areas?

- How can specialist schools work most effectively in families of schools to share the benefits of specialisation and help raise standards for all?

- In what ways can the Grid best be developed to ensure that all learners have access?

[page 76]

- What needs to be done to encourage educational, media and business organisations to collaborate in the development of research into innovative approaches to schooling?

Additional consultation is being undertaken on:

- the establishment of Education Action Zones.

Chapter 5: Teaching: High status, high standards (page 45)

- What skills and competencies should be covered by a mandatory headship qualification and does the NPQH fulfil these requirements?

- What should be the timetable for introducing the mandatory requirement?

- How can we develop an effective fast-track route to headship?

- What should be the priorities for the training and development of newly appointed and serving headteachers?

- What should newly qualified teachers be required to do in their first year to develop their practical skills?

- What arrangements would be needed for confirming Qualified Teacher Status at the end of a successful induction year?

- How should Advanced Skills Teachers be selected and what functions should they be expected to carry out?

- How can current headteacher and teacher appraisal arrangements be sharpened up to provide an early indication of development needs and targets for improvement?

- How should teaching assistants and associates be used in schools?

Chapter 6: Helping pupils achieve (page 53)

- What good examples of family learning are there in your area which might be a model for others?

- What specific commitments and undertakings do you think would be most appropriate for (a) a primary school and (b) a secondary school home-school contract?

- What information should all pupil reports, prospectuses and annual reports be required to contain, and what should be left to the school's discretion?

- What form should the homework guidelines take, and how can they be made most effective in practice?

- How best should we develop a national framework for pupil motivation that promotes national and local action effectively?

- What should programmes for citizenship and parenting cover?

Additional consultation is being undertaken on:

- detailed guidance for schools and LEAs on pupil discipline and attendance; and

- a new national framework for motivating pupils outside the classroom; and

- national nutritional standards for school meals.

[page 77]

Chapter 7: A new partnership (page 66)

We will publish for consultation later this summer details of how the new framework will work, paving the way for legislation in the autumn. That will cover in particular consultation on: the foundation, community and aided structure; the role of LEAs; revising the rules for Local Management of Schools; devolving decision making on the supply of school places: and procedures for deciding school admission arrangements. We have also established a consultative group representing the main national organisations to help us work up the detail. We will consult separately about ways of improving partnership between the state and independent sectors.

Meanwhile, we welcome comments on the proposed framework, in particular:

- Are the principles set out in paragraph 3 of Chapter 7 for designing the new framework of foundation, community and aided schools the right ones?

- Does the role of LEAs described in paragraphs 17-19 of Chapter 7 include the right functions?

- What are the best arrangements for a local partnership in planning the organisation of school places?

- What are the main characteristics of effective locally co-ordinated admission arrangements, and how can they best be encouraged?

- How can we ensure that as many parents as possible have a place for their child at their preferred school, without considerable extra expense adding to the number of unfilled school places overall?

[page 78]

Appendix: Achievement in our schools

1 This Appendix sets out recent data on achievements in schools in national curriculum tests and at GCSE. It gives some comparisons between boys and girls, and between ethnic groups. It also includes comparisons of performance between groups of schools with similar intakes as measured by the take-up of free school meals. Finally, some international comparisons from the recent Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) are shown.

National Curriculum assessment

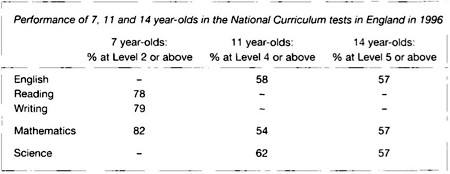

2 The table below shows that four out of five 7 year-old pupils in 1996 reached the standard expected of them in English and mathematics, and that achievement at age 11 was well below this. Only 54% of 11 year-olds reached the standard in mathematics expected for their age and in English only 58% reached the standard. Achievement at age 14 shows a similar picture, with well over a third of 14 year-olds not achieving the level expected for their age in either English, mathematics or science.

[page 79]

GCSE

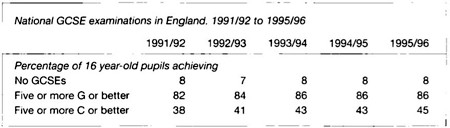

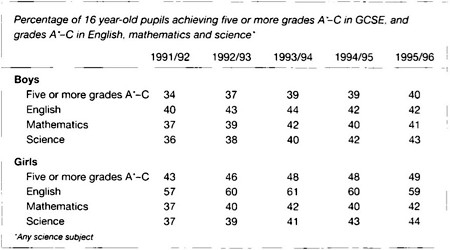

3 Information from public examinations provides a longer-term picture of national achievement. The table below shows that fewer than half of 16 year-olds achieve five or more GCSEs at grade C or better, and the rise in this proportion has slackened recently. Furthermore, in 1996 only around one-third of pupils gained a grade C or better in both mathematics and English.

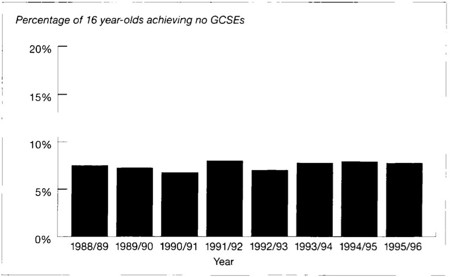

4 The table also shows that the proportion of pupils achieving five GCSEs at any grade has also risen very little recently. The proportion leaving school with no GCSEs at all has remained stuck at around 1 in 12 of all pupils, as is shown in the chart below.

[page 80]

Achievements of boys and girls

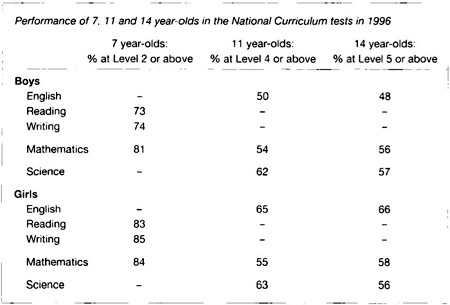

5 From the table below it can be seen that girls outperform boys at 7. 11 and 14 in National Curriculum tests in English, with the gap widening with age. Their achievements in mathematics and science are broadly similar.

6 This picture persists at age 16, as shown below. 49% of all girls achieved five or more higher grade GCSEs, compared to only 40% of boys. As at earlier ages, achievements in mathematics and science are roughly the same, but in English 6 out of 10 girls achieved a grade C or better compared to only 4 out of 10 boys.

[page 81]

Ethnic minorities

7 There are no national data on achievement by pupils from different ethnic minorities. But the latest survey of research by OFSTED suggests that there are some common patterns. Indian pupils appear consistently to achieve more highly, on average, than pupils from other South Asian backgrounds and white counterparts in some, but not all, urban areas. Bangladeshi pupils' achievements are often less than other ethnic groups. African-Caribbean pupils have not shared equally in the increasing rates of educational achievement: in many LEAs their average achievements are significantly lower than other groups. The performance of African-Caribbean young men is a particular cause for concern.

Variation between schools with similar intakes

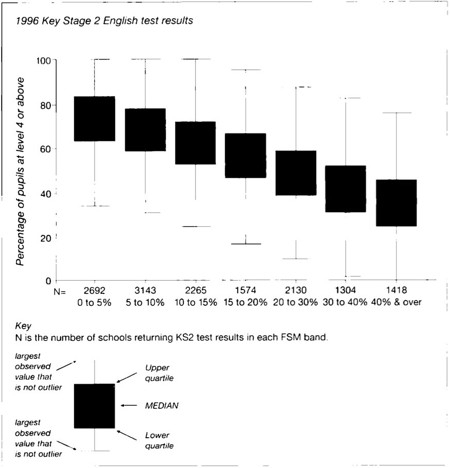

8 More detailed study of the national data shows that schools with broadly similar intakes (here measured by the proportion of pupils taking up free school meals) have widely differing achievements. Furthermore, using KS2 English test results as an example, the chart below shows that almost one quarter of schools in the most deprived areas (in this case with at least 40% of their pupils receiving free school meals) get at least half their pupils to level 4 or above, the level expected for that age. Some schools with less than 5% of their pupils receiving free school meals did not achieve as good results.

[page 82]

International comparisons

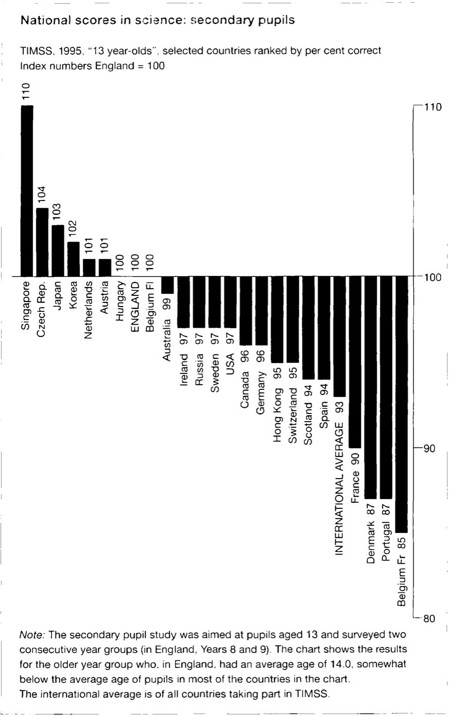

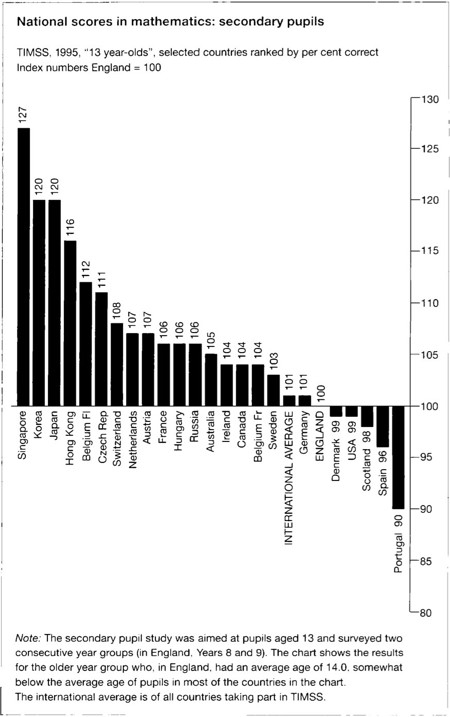

9 In a recent major study, in 1995. English pupils scored below the majority of advanced industrialised economies in mathematics in both primary and early secondary school but performed much better in science, particularly at early secondary level where they were amongst the best in Europe. English performance in these two subjects (which of course are just a part of any country's school curriculum) is therefore mixed but relatively few countries outperformed England on both subjects at the early secondary level.

10 A number of other countries showed a similar pattern of greater strength in one subject than in the other such as France. Switzerland. Hong Kong, French-speaking Belgium although, for these, mathematics was their stronger subject. This balance of strength and weakness will, in part, reflect differences in the age at which topics are introduced into the curriculum and the weight they receive as well as any differences in pupil and teacher competence.

11 More detailed figures show that, in mathematics, English pupils were particularly weak in basic number and fractions and also in algebra. It also seems that, again in mathematics, our best performing pupils (the top 10%) are somewhat better placed relative to other countries than are our average performers but it also seems that our lowest attainers perform disproportionately poorly. In science our high average performance means that our best pupils do particularly well by international standards with some 17% reaching or exceeding the level of the top 10% internationally, a proportion on a par with Japan and Korea.

[page 83]

[page 84]