[page 25]

CHAPTER IV

Changes in Structure and National Planning for Higher Education

4.1 Previous chapters have indicated the range of sound achievement in recent years; there is much to be proud of in all sectors of higher education in this country. But they also draw attention to weaknesses in the management and structure of the system. These are serious in much of the sector of higher education in England which contains the polytechnics and the maintained and grant-aided colleges, and the following paragraphs announce radical changes here. Significant development is also needed in the shape and constitutional position of the University Grants Committee (UGC), as examined in the Report of the Croham Committee's Review. This chapter covers that matter also, including particular reference to future planning and funding arrangements for the Scottish universities.

THE POLYTECHNICS AND COLLEGES SECTOR IN ENGLAND

4.2 This sector of higher education has in recent years been commonly called "the public sector of higher education". But it is misleading to imply a fundamental divide between universities and other institutions also providing higher education and also heavily dependent on public funds. The Government finds the term "public sector" used in this way unhelpful and, moreover, inconsistent with its desire to see all higher education institutions do more to attract private funding. It therefore seeks to lead a move away from use of this term to describe a part of higher education and, in its place, this White Paper speaks throughout of the "polytechnics and colleges sector".

Background

4.3 In England 405 institutions outside the universities provide higher education: 29 polytechnics and 346 other colleges under local education authority (LEA) control, plus 30 voluntary and other colleges directly funded by the Department of Education and Science (DES). Most of these institutions are provided .and maintained by LEAs and are, in effect, part of them: their land, buildings and equipment belong to the authority and their staff are its employees. Others - generally known as assisted institutions - are separately established, some as corporate bodies, but with constitutions linking them to the LEA on whose financial assistance they substantially depend.

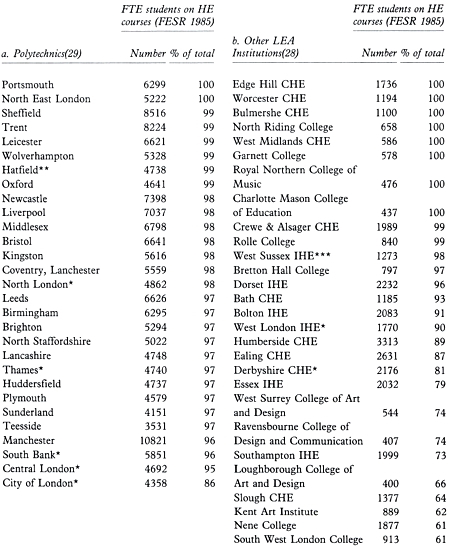

[page 26]

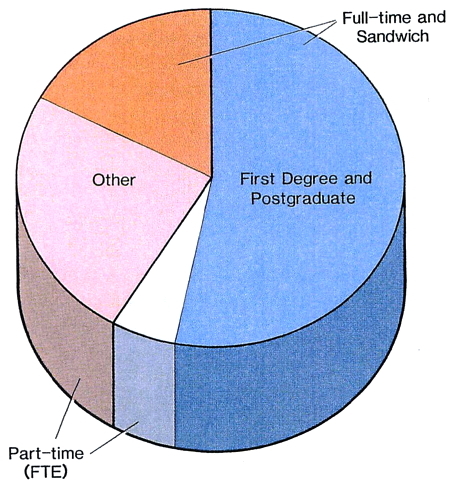

Figure L: Students in Polytechnics and Colleges: Level of Study and Mode of Attendance - England 1985

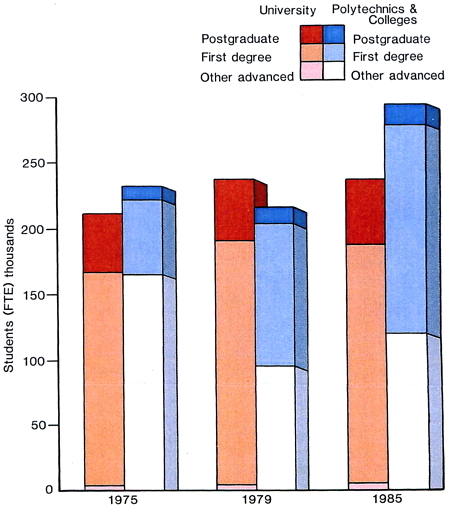

Figure M: Levels of Study in Universities and Polytechnics and Colleges - England 1975-85

[page 27]

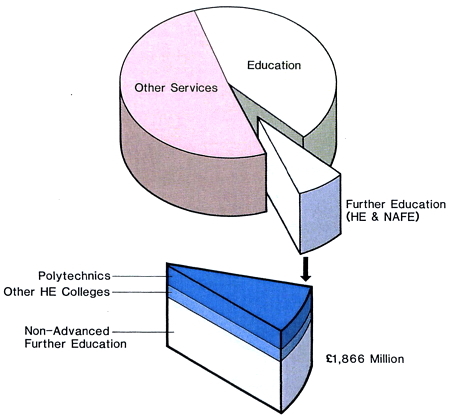

Figure N: Local Authority Recurrent Expenditure:

Further Education's Share 1986-87

4.4 The polytechnics and colleges playa distinctive and increasingly important part in higher education, particularly in technological and other vocational fields. They provide for over half the higher education students in England.

4.5 The resources devoted to higher education outside the universities in England in 1986-87 amounted, excluding student maintenance, to some £978 million (current) and £87 million (capital). Most of the expenditure of the local authority colleges is pooled between all authorities. The Secretary of State for Education and Science determines the total amount which can be pooled and allocates funds and places between individual colleges and areas of study in the light of advice from the National Advisory Body for Public Sector Higher Education (NAB). The local authorities have 6 out of 8 seats on the NAB Committee.

Transfer of Major Colleges from Local Government

4.6 The Government acknowledges the contribution which local government has made to the development of higher education and recognises that many local authorities handle their responsibilities for their higher education colleges

[page 28]

constructively. It has, however, concluded, for the reasons set out below, that it is no longer appropriate for polytechnics and other colleges predominantly offering higher education to be controlled by individual local authorities:

Role

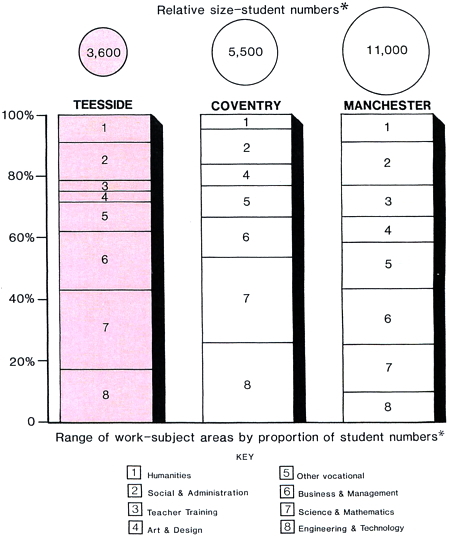

- Polytechnics have strong national, as well as regional and local, roles. They recruit students nationally and meet the needs of employers nationwide.

- Polytechnics offer all major subjects except medicine. After two decades they are firmly established and cater on average for a larger number of students than universities.

- They, other colleges maintained and assisted by local authorities, and the voluntary and other grant-aided colleges, are acknowledged to make a high-quality contribution to higher education, distinct from that of the universities.

Figure O: What Polytechnics Do

*Full-time equivalents

[page 29]

Planning

- The funding arrangements for higher education in the polytechnics and colleges have long recognised that it is neither desirable nor appropriate for each local authority to plan and fund its institutions in isolation. Few local authorities are able to promulgate a policy for higher education in their institutions even though they have responsibility for determining the character of educational provision in their areas.

- The existing national planning arrangements are unsatisfactory. More progress needs to be made in rationalising scattered provision and concentrating effort on strong institutions and departments.

- Progress in educational planning will be even more necessary if the polytechnics and other colleges are to meet the changing needs of industry and commerce in the 1990s and provide in new ways for the wider range of students discussed in Chapter II.

- This calls for a more effective lead from the centre and the reward of success and enterprise in meeting new national needs, in place of a system giving undue weight to local interests.

- In particular, polytechnics should be free from local constraints and encouraged to build on their individual strengths so that some at least can become recognised leaders in particular vocational and technological fields.

Management

- It is widely acknowledged that the present relationship between local authorities and their polytechnics and colleges can and often does inhibit good institutional management. It also inhibits the desirably closer relationship between institutions and industry and commerce through consultancy and other services.

- Many local authorities apply to their higher education institutions inappropriate detailed controls, some of which are designed for much smaller institutions or other services.

- The governors, directors/principals and other senior staff of many polytechnics and colleges are prevented from managing their financial and staffing resources to best effect, and from developing to the full the maturity and responsibility appropriate to higher education institutions.

4.7 It has been suggested that the simple grant of corporate status to polytechnics and other local authority colleges would satisfactorily resolve these management difficulties. The Government does not agree. Even if institutions had corporate status, local authorities would still be able to impose financial and staffing constraints by attaching conditions to their funding. Nor would grant of corporate status do anything to remedy deficiencies in the present national planning arrangements. It is more likely that widespread grant of corporate status would serve only to create new tensions between supposedly self-managing institutions and local authorities which would continue to see themselves as ultimately responsible for the institutions' financial and academic policies.

4.8 The Government therefore intends to secure the re-establishment of the polytechnics and other institutions of substantial size engaged predominantly in higher education as free-standing outside local authority control. By "of substantial size" is intended colleges with 350 or more full-time equivalent home and European Community higher education students; and by "engaged predominantly in higher

[page 30]

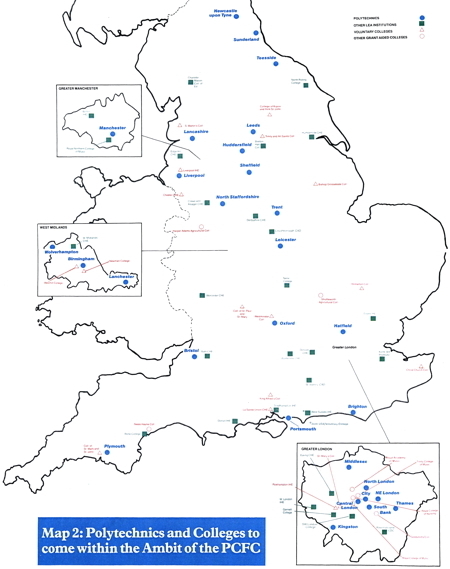

education" is meant colleges with more than 550/0 of their activity in higher education - both measured by the latest available Further Education Statistical Record (FESR), that for 1985. The institutions which will be transferred from local government are the 57 shown in Annex C and on Map 2. Those predominantly higher education institutions with fewer than 350 students will have the choice to opt in to the new arrangements; they are listed in Annex D. Those colleges whose main concern is non-advanced further education will remain with local government.

Arrangements for the Voluntary and Grant-Aided Colleges

4.9 The Government intends that the new arrangements should also apply to the voluntary and other grant-aided colleges providing higher education, which are already free-standing institutions funded by the Department of Education and Science. These are also shown on Map 2 and are listed in Annex E. Special considerations, however, apply to two colleges - Cranfield Institute of Technology and the Royal College of Art - which provide predominantly for postgraduate students (see paragraph 4.48).

Institutions in the New Sector

4.10 The polytechnics and other colleges transferred from local authorities will each:

- be established with corporate status;

- have governing bodies with strong representation from local and regional industry, commerce and the professions, and on which dominance by local authority representatives is no longer possible;

- employ their own staff; and

- own their land, buildings and equipment, subject to the transitional arrangements described in paragraphs 4.26-27.

4.11 There is no intention that the local and regional links and roles of the institutions concerned should be diminished; on the contrary these should remain a distinctive feature. Local links have usually been formed by the efforts of institutions rather than through the agency of the local authority. It is the Government's conviction that they will want to continue these efforts and that the regional dimension could be strengthened with removal of the single local authority tie.

4.12 The Board of Governors of each institution will comprise 20-25 people, of whom about half will be local and regional employers or representatives of the professions. The initial composition of the employer/professions group will be approved by the Secretary of State on the basis of local advice; thereafter its members will select their successors after consulting relevant local bodies. Other members will be appointed by named constituencies in stated proportions or co-opted. Each Board will elect its own Chairman.

4.13 The Governors will have wide powers to determine the affairs of the institution. The Director of each institution will report only to the Governors.

4.14 The academic work of all the institutions in the new sector will continue to be validated by the Council for National Academic Awards, universities or the Business and Technician Education Council as appropriate, and will be subject to inspection by Her Majesty's Inspectorate.

4.15 The provision of public money on the appropriate scale for the colleges transferred from local government will become the responsibility of central Government. The equivalent of pooled expenditure will be transferred out of Aggregate Exchequer Grant (AEG) and capital expenditure in the transferred colleges will be deducted from provision for local authority capital expenditure.

[page 31]

Certain of the transferred institutions currently receive resources from their LEAs over and above the allocations from the pool. The Government expects LEAs to phase out such subsidies before the transfer in continuation of recent trends: it will consider in the light of progress towards this objective whether to take account of the extent of any remaining subsidy either in the adjustment of AEG consequent on the transfer of these institutions or by other means.

Funding: the Government's Approach

4.16 Polytechnics and colleges are at present almost wholly dependent on public funds for their recurrent and capital expenditure. The funds they receive have usually been described as "allocations" or "grants", paid by a local authority or central Government. Payment of such grants from public funds does not imply, in the Government's view, unconditional entitlement to support from the taxpayer at any particular level. The resources made available are intended to secure delivery of educational services which are of satisfactory or better quality and which are responsive to the needs of students and employers. Institutions receiving public funds are accountable for the uses to which the funds are put and for the effectiveness and efficiency with which they are employed.

4.17 The Government therefore proposes, in place of grants, a system of contracting between institutions and the new planning and funding body described in the following paragraphs. Its intention in making this change is to:

- encourage institutions to be enterprising in attracting contracts from other sources, particularly the private sector, and thereby to lessen their present degree of dependence on public funding;

- sharpen accountability for the use of the public funds which will continue to be required; and

- strengthen the commitment of institutions to the delivery of the educational services which it is agreed with the new planning and funding body they should provide.

The Government recognises that a system of contracting must be so designed as to avoid damage to aspects of the work of institutions, such as the advancement of learning, which cannot readily be embraced by specific contractual commitments. It also acknowledges that the system must make allowance for the time needed to develop courses to the point at which they become operational and start to recruit students.

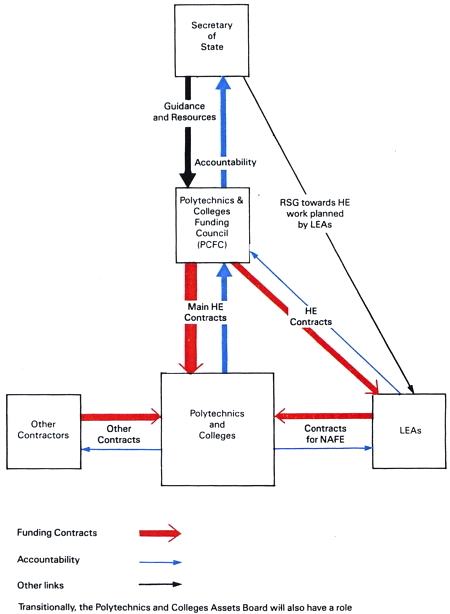

Funding: Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council (PCFC)

4.18 The new polytechnics and colleges sector of higher education will comprise: the transferred colleges listed in Annex C; such small institutions from the list. in Annex D, as choose to opt in; and the voluntary and other grant-aided colleges listed in Annex E. The planning of this sector and the allocation of resources within it will require the establishment of a new body, which it is proposed to call the Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council (PCFC). The NAB with its local authority majority will cease to be an appropriate planning body and will go out of existence. The Government will consult the voluntary colleges about whether the Voluntary Sector Consultative Council should continue and, if so, about its relationship to the PCFC.

4.19 The PCFC, like the Universities Funding Council (present UGC - on whose development see paragraphs 4.38ff), will be an independent non-departmental body appointed by the Secretary of State for Education and Science. It will have a small membership with a strong industrial and commercial element, as well as members from higher education institutions. The Secretary of State will provide general guidance to the PCFC on its work and will have reserve powers of direction. The

[page 32]

Council will be expected to consult the local authorities about their residual interest in higher education and about the small amount of non-advanced further education in the transferred colleges (see paragraphs 4.24 and 4.25).

4.20 The main tasks of the PCFC will be to:

- contract with institutions, using the recurrent funds supplied by Government, for the provision of higher education including, where appropriate, the development of new courses and selective initiatives and research activities;

- make funds available for capital expenditure by institutions, from those supplied by Government and from any money available for re-cycling from disposals by institutions of property acquired with public funds (but see also paragraph 4.26);

- subject to what is said in paragraph 4.23 about initial teacher training, plan the educational provision in the sector;

- encourage institutions to co-operate in the development of good management practice; and

- have power to contract for provision of some of the higher education in colleges which remain under the control of local authorities (see paragraph 4.24).

The Government will consult further on the PCFC's precise terms of reference.

4.21 The development of the system of contracting discussed in paragraphs 4.16-17 will be a matter for the PCFC, subject to any guidance from the Secretary of State. Before contracts are entered into, the PCFC will assess the performance of institutions. Any serious failure to meet the terms of a previous contract may result in revised terms or a failure to renew. The Government will provide the PCFC with indications of future levels of funding in the normal way through its published public expenditure plans.

4.22 The PCFC will also have an interest in the pay of staff in the transferred colleges related to its responsibilities for funding. The Government will be considering further the arrangements for determining the pay of academic staff (see also paragraph 4.47).

Teacher Training

4.23 The institutions within the ambit of the PCFC will include those providing almost all initial teacher training courses outside the universities. As in the past, the Secretary of State for Education and Science will not only approve individual courses with regard to their suitability as courses of initial training for school teachers, but also set individual course entry targets at individual institutions. He would wish to be able to base these decisions on advice from the PCFC, which would take into account both criteria provided by the Secretary of State for initial teacher training and its planning work across the new sector of higher education. But to operate in this way will require arrangements which result in delivery to the Secretary of State of advice on a timetable which meets his needs and that of the institutions. If that does not prove possible, the Secretary of State will need to rely on internal Departmental advice, developed in consultation with the PCFC. As for courses of in-service teacher training, the PCFC will contract with institutions for the provision of those leading to a recognised qualification and lasting at least a year full-time or the part-time equivalent. Shorter in-service courses will be funded entirely through fees.

Colleges and Provision Remaining with Local Authorities

4.24 The colleges listed in Annex C have nearly 80% of the full-time equivalent higher education students currently in higher education institutions maintained or

[page 33]

assisted by local authorities. Much of the work in the remaining local authority colleges meets essentially local needs: professional and technical vocational education, including Higher National Certificates (HNCs), offered part-time. But some of the colleges have degree level work - some 7% of the present total - and full-time Higher National Diploma (HND) and equivalent courses. For the colleges remaining under local authority control, the Government intends that:

- for all degree and postgraduate work, full-time HND and Diploma of Higher Education (DipHE) and equivalent courses, and for courses of in-service teacher training leading to a recognised qualification and lasting at least a year full-time or the part-time equivalent: the PCFC will be responsible for planning and funding. In this situation it will, to the extent and in the locations it judges appropriate, enter into contracts with local authorities for the purchase of provision from their colleges. The adjustment of AEG in respect of the transfer of responsibilities for higher education will take account of this reduction in LEA liabilities;

- for other courses, including all part-time sub-degree provision, whether leading to BTEC, professional or other qualifications: the local authorities will no longer be guided by a central planning agency. The present pooled funding arrangements will end. LEAs will instead receive credit for students on such courses in the assessment of their Grant Related Expenditure for Rate Support Grant purposes.

Non-advanced Further Education Provision

4.25 As part of their continuing responsibility for non-advanced further education (NAFE), it will be open to LEAs to make contractual arrangements for it to be provided in colleges transferred from their control. The arrangements for reducing the Aggregate Exchequer Grant on account of the transfer, and for the assessment of Grant Related Expenditure, will recognise authorities' continuing responsibility for NAFE.

Transfer of Assets

4.26 A Polytechnics and Colleges Assets Board (PCAB) will be set up for a limited period. Its main tasks will be to resolve any difficulties in the apportionment of assets to transferred institutions and to assist them to make arrangements as quickly as possible for the holding of their own assets. Any assets which are not assigned to institutions when they become corporate bodies will be held transitionally by the PCAB. It will charge peppercorn rents for the use of such assets. It will also then have a duty to make available to the PCFC any surplus assets or the proceeds of any sale of assets, so that the PCFC can apply them for other purposes within the new sector of higher education, subject to a reserve power of direction by the Secretary of State for Education and Science. The Chairman and members of PCAB will be appointed by the Secretary of State.

4.27 The assets now used in local authority higher education were acquired in most cases under arrangements which shared the cost between ratepayers and taxpayers on a national basis, to form part of the national provision of higher education. They will continue to serve that purpose. Accordingly, the local education authorities will not be compensated for the transfer of the assets now in their ownership. The institutions themselves will become responsible for servicing the debt attributable to past capital expenditure once ownership has transferred to them; this obligation will be taken into account in determining the funding available to them through the PCFC. In the meantime the PCAB will meet the debt charges associated with any assets that it holds. The claims made by local education authorities on the pool out of which debt charges in respect of local authority higher education are at present serviced will provide a bench-mark for assessing the debt to be transferred.

[page 34]

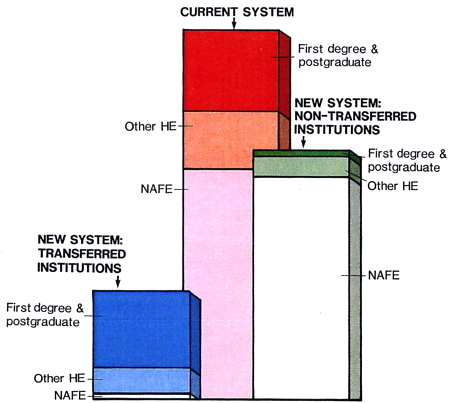

Figure P: Summary of New Structure

Administration and Costs of the PCFC and the PCAB

4.28 The PCFC will require a secretariat, and some of the colleges may need additional staff to taker-over financial and other management tasks currently undertaken by their LEAs. There will also be temporary costs associated with the PCAB. But these costs will be offset by consequential savings in LEAs, in DES by the transfer of the funding of the grant-aided institutions to the PCFC, and by the winding-up of the NAB. The running costs of the PCFC and the PCAB will be subject to the normal requirements for non-Departmental public bodies.

Possible Designation of Additional Polytechnics

4.29 One question to which some attention has been given recently is whether some among the existing colleges to be taken into the new sector might merit designation as additional polytechnics. The Government has decided to ask the PCFC to include amongst its early tasks an assessment of whether further

[page 35]

designations would be appropriate. The PCFC will have to approach this within the resources available for the sector as a whole, but it should do so in a positive spirit, paying attention not only to candidates' attributes but also to their capacity to expand to meet national and regional needs.

Legislation

4.30 The Government intends to introduce a Bill as soon as Parliamentary time permits to secure the re-establishment of maintained colleges as free-standing corporate bodies, the consequential transfer of assets, staff and debts, the establishment of the PCFC and the PCAB and the changes in the funding and other arrangements described in this White Paper. In the meantime the Government will be consulting relevant interests about the detailed legislative provisions.

4.31 The necessity for legislation will mean some delay before the new arrangements can take effect. The Government is confident that during this period local authorities will continue to act responsibly in the funding of the institutions due for transfer and in the upkeep of their plant. The Government will monitor the position carefully with the intention of ensuring, where necessary, that the interests of present and future students are not placed in jeopardy.

Conclusions

4.32 The Government believes that the major reform just described in outline will provide a much improved setting within which the polytechnics and colleges can pursue educational effectiveness and efficiency, can develop entrepreneurial skills and attitudes, and can respond to national needs. At the same time, their regional

Figure Q: Distribution of Polytechnic and College Students* - Present and Proposed Systems

*Full-time equivalents.

[page 36]

and local roles should be in no way diminished; indeed the reconstruction of their governing bodies may enhance their capability there too. As corporate bodies, no longer controlled and funded by local authorities, these colleges will be free to manage their resources flexibly and to best advantage, while being accountable through the PCFC for their use of public funds.

4.33 At the same time the PCFC itself will be constituted with the scope to operate far more effectively than the NAB has done. It will, moreover, be able to concentrate its attention on institutions which are predominantly concerned with higher education of national relevance; with the local authorities correspondingly retaining charge of institutions where primarily local needs are being served.

THE POLYTECHNIC AND COLLEGES SECTOR IN WALES

4.34 In Wales 22 institutions outside the universities provide higher education: one polytechnic, 20 other local authority maintained institutions and one voluntary college directly funded by the Welsh Office. The local authority maintained institutions are funded on the same basis as their counterparts in England. The Wales Advisory Body for Local Authority Higher Education (WAB) advises the Secretary of State for Wales on the distribution of student places and on the allocation of expenditure from the Advanced Further Education Pool. There are 14,000 full-time equivalent students on higher education courses in the polytechnic and colleges sector in Wales, compared with 21,000 full and part-time students in the University of Wales.

4.35 Only five of the local authority maintained institutions and the one voluntary college are engaged predominantly in higher education and have more than 350 full-time equivalent students. Nearly a fifth of the provision at these institutions is non-advanced further education courses.

4.36 As the polytechnic and colleges sector in Wales is small, it is capable of being planned and developed through the WAB, provided the interests of individual local authorities are subordinated to the interests of the sector as a whole. The WAB - which came into being later than the NAB - is currently reviewing courses in a number of subject areas with a view to rationalising provision where this is necessary. The results of these reviews will indicate whether the WAB is able to offer advice based on national, as opposed to local, considerations. They will also show whether the WAB, the UGC (and its successor) and the University of Wales can work successfully together to develop a coherent system of higher education across all sectors in Wales.

4.37 The Government expects the WAB to maintain its ability to operate as a national advisory body. It is not at present the Government's intention therefore to establish a Polytechnic and Colleges Funding Council for Wales. However the legislation which will be brought forward to establish a PCFC in England will provide for the same arrangements to be extended to Wales if the Government subsequently considers that to be necessary.

UNIVERSITY FUNDING: THE UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMITTEE AND ITS SUCCESSOR

4.38 The forty-seven universities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have their own identity defined by Royal Charter or Statute. Except for the University of Buckingham, they are funded by central Government; and, the Open University apart, they receive the greater part of their public funding effectively by

[page 37]

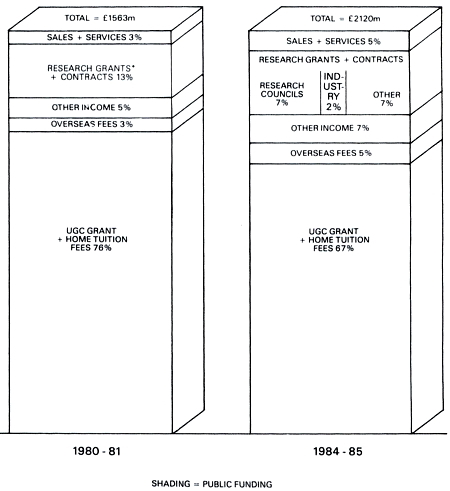

Figure R: Proportions of University Income by Source

*Data on sources of research funding not collected until 1981-82

decision of the UGC. Following a recommendation by the Steering Committee for Efficiency Studies in Universities, under the Chairmanship of Sir Alex Jarratt, the Government established in July 1985 a Committee chaired by Lord Croham to review the UGC's constitutional position, role and structure.

4.39 The Croham Report was published on 10 February 1987. (14) Its chief conclusions were that the UGC should be reconstituted as a University Grants Council, an independent body under the sponsorship of the Secretary of State for Education and Science, with revised terms of reference, a chairman with substantial experience outside the academic world, broadly equal numbers of academic and non-academic members, and a reserve power for the Secretary of State to issue directions to the Council. It recommended that the new Council should be formally incorporated, preferably by legislation.

4.40 The Government accepts the broad thrust of these recommendations and intends to include appropriate provision in the Bill which will give effect to its proposals on polytechnics and colleges (paragraph 4.30). However, just as in that sector of higher education, the Government proposes for the university sector that payment of grants to institutions should be replaced by a system of contracting between them and the body to succeed the UGC. That body will be named the

(14) Review of the University Grants Committee Cm 81 (HMSO 1987).

[page 38]

Universities Funding Council (UFC) - which form is used in the discussion below of the Croham recommendations. The Government will be giving further consideration, in the period up to the introduction of legislation, to the precise terms of reference of the UFC, and in that process will take into account what may be said during its consultations on the Croham recommendations. It wishes to emphasise, however, that the UFC's essential responsibilities should relate to the allocation of funding between universities rather than to its overall amount, which is a matter for Government to decide after considering all the evidence.

4.41 The Government welcomes and endorses the following other recommendations of the Report. All of them build to some extent on present practice and development, and further progress in these directions should be made even before the new UFC is constituted.

- The Government should provide guidelines at appropriate intervals to set the framework for the planning process which the UFC and the universities should conduct.

- The Government should play no part in the distribution of general funding between individual universities in Great Britain.

- The UFC for its part should have the power to require that funding is or is not spent for a particular purpose.

- Financial relations between the Government and the UFC, and between the UFC and universities, should be governed by financial memoranda.

- Arrangements for the flow of management information and for accountability from the universities to the UFC and onwards to Government should be much improved.

4.42 In addition to early guidelines from Government to assist the UFC's planning work, the Report recommends that, so long as the general rate of inflation is expected to be below 5%, the funds made available by the Government to the UFC and by the Council to the universities should be set in cash terms for a period of three university financial years and should not be reduced except in a national emergency. The Government is not convinced that such an arrangement would necessarily work to the universities' advantage and believes that it would be undesirable to insulate university management from the need to plan for changing circumstances. It recognises the importance of giving higher education institutions as much advance information as possible about the total resources likely to be made available and aims to do this through the public expenditure planning process - in effect a rolling programme rather than a fixed triennium. Against that background it will be for the new UFC to give universities planning parameters for the medium and long terms.

4.43 The Croham Report makes a wide range of other recommendations. With the exception of that concerning the proposed UK Education Commission (see paragraph 4.50) and what the Report has to say on the Scottish position (see paragraphs 4.44-45), the Government is still considering these and would welcome comments on them by 30 June. These other matters concern principally the direction, structure and staffing of the new Council; the information needed for its work; the arrangements for resource allocations to universities; and specific aspects of the Council's responsibilities, including in respect of medical education. The Government will, in particular, be concerned to see that the UFC's arrangements for making funds available to universities properly reward success in developing co-operation with and meeting the needs of industry and commerce. As regards medical education, the Government is already taking steps to improve co-ordination between the universities and the National Health Service at all levels. The DES and Health Departments have issued for the first time joint guidance on provision for medical education.

[page 39]

HIGHER EDUCATION IN SCOTLAND

4.44 The Scottish Tertiary Education Advisory Council (STEAC) report Future Strategy for Higher Education in Scotland (Cmnd 9676) recommended establishment of a body with responsibility for academic planning across the university and non-university sectors of higher education in Scotland and for allocation of resources within a system of funding unified under the Secretary of State for Scotland. This recommendation was subject to certain conditions, including the existence of a satisfactory UK-based peer review system for teaching and research in the Scottish universities and adequate safeguards for the Scottish universities in relation to access to research council funding. The Advisory Board for the Research Councils (ABRC) has advised the Government that no additional measures would be necessary to safeguard access by Scottish universities to research council funds. The Croham Report concluded that, if a Scottish planning and funding body of the kind proposed were to be established, it should be incumbent on both that body and the UFC to consult each other whenever a policy development might have a limiting effect on the mobility of students or staff or the pattern of UK provision in particular subjects. The Croham Report also recommended that, if such a Scottish planning and funding body were not established, the UFC should set up a Scottish Committee.

4.45 The Government agrees with STEAC's view that there is scope for improvement in the co-ordination and planning of the university and colleges sectors of higher education in Scotland. Equally, however, it is concerned to ensure that the planning and funding of the eight Scottish universities is not divorced from that of universities elsewhere in the United Kingdom. The Government has therefore decided that the remit of the new Universities Funding Council should cover all the universities currently funded on the advice of the UGc. The Council should, however, appoint a Scottish Committee after consultation with the Secretary of State for Scotland and in the development of its policies take account of advice from this Committee. The UFC would have regard to the views of the Secretary of State for Scotland on Scottish needs and plans for the colleges sector of higher education in Scotland, consistent with the national guidelines provided by the Secretary of State for Education and Science.

HIGHER EDUCATION IN NORTHERN IRELAND

4.46 The Government accepts the Croham Committee's recommendation that the UFC should advise the Department of Education for Northern Ireland on the funding of the universities in Northern Ireland. It intends that these two universities should continue to be funded on the basis of parity of provision with institutions in Great Britain. In formulating its advice, the UFC will take account of the views of a Northern Ireland Working Party which, as now, will consider and report on particular circumstances bearing on higher education provision in the Province.

OTHER ISSUES

Academic Pay in Higher Education

4.47 The Croham Report comments briefly on the arrangements for determining academic salaries in the universities. Pay levels and the pay structure 'have to be devised so as to enable the universities to recruit, retain and motivate staff within the available resources. The Report notes that the existing negotiating arrangements for academic salaries were established before the present funding arrangements were introduced, and it recommends a re-examination of the arrangements. The Government agrees, and will shortly open discussions to that end. The Government will at the same time be considering what arrangements should be adopted in the polytechnics and colleges sector.

[page 40]

The Open University, Cranfield Institute of Technology and the Royal College of Art

4.48 As the Croham Report noted, these three institutions are currently planned and funded separately from the rest of higher education with direct funding from the Department of Education and Science on the advice of Visiting Committees appointed by the Secretary of State. The Government recognises that these institutions each have certain features which may continue to justify special arrangements, but will be discussing with each the possibility of its coming within the ambit of one of the proposed new planning and funding bodies.

Planning of Higher Education

4.49 The Croham Report discusses the planning of the whole of higher education as part of the context for its review of the UFC's role, and notes the statement in Cmnd 9524 that the Government saw no practical scope for a united planning body for higher education of the kind comprehended by the term "overarching body". The Government reaffirms that view. It recognises its own responsibilities for higher education planning and policy and attaches importance to those features which distinguish universities and other higher education institutions. Many of those features are valuable in their own right and continue to call for separate planning and funding arrangements.

4.50 The Croham Report goes on, however, to propose the establishment of a United Kingdom Education Commission to advise on national needs in relation to the education system. This recommendation runs well beyond advice on national needs in relation to higher education and raises a number of fundamental questions about the desirability and usefulness of purely advisory bodies and about the difficulty of manpower planning which have been long debated. The Government is not at this stage persuaded that such a Commission would be helpful and believes that the statements about future access to higher education in Chapter II contribute to the assessment of national needs for higher education which rightly concerned the Croham Committee.

4.51 Moreover, setting up the polytechnics and certain other colleges in England as free-standing institutions to be funded by central Government, no longer under local authority control, on the lines proposed in the first part of this chapter, will make it easier for the Government and its partners both to secure more collaboration at all levels across the binary line and to co-ordinate assessments of and responses to national needs. The PCFC, as well as - and sometimes in concert with - the UFC, will be in a position to consult about and reach agreed views on matters of demand and supply, and rationalisation where necessary. The development of co-operation at institutional level, despite the hopes expressed in the 1985 Green Paper, has made less progress than the Government would have hoped. The new planning structures, together with the continuing local and regional ties of the polytechnics and colleges especially, should provide a useful basis for further effort.

[page 41]

ANNEX A

List of Abbreviations Used

| ABRC | Advisory Board for the Research Councils

|

| AEG | Aggregate Exchequer Grant

|

| A level | Advanced level

|

| API | Age Participation Index (see footnote 4, page 3)

|

| AS level | Advanced Supplementary level

|

| BRITE | Basic Research in Industrial Technologies for Europe

|

| BTEC | Business and Technician Education Council

|

| CATS | Credit Accumulation and Transfer Scheme

|

| CDP | Committee of Directors of Polytechnics

|

| CHE | College of Higher Education

|

| CIs | Scottish Central Institutions

|

| CNAA | Council for National Academic Awards

|

| CVCP | Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals

|

| DES | Department of Education and Science

|

| DipHE | Diploma of Higher Education

|

| ECCTIS | Educational Counselling and Credit Transfer Information Service

|

| ESPRIT | European Strategic Programme for Research in Information Technology

|

| ETP | Engineering and Technology Programme

|

| FESR | Further Education Statistical Record

|

| FTE | Full-Time Equivalent (see footnote 6, page 5)

|

| GCE | General Certificate of Education

|

| GCSE | General Certificate of Secondary Education

|

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product

|

| HE | Higher Education

|

| HMI | Her Majesty's Inspectorate

|

| HMSO | Her Majesty's Stationery Office

|

| HNC | Higher National Certificate

|

| HND | Higher National Diploma

|

| IHE | Institute of Higher Education

|

| LEA | Local Education Authority

|

| NAB | National Advisory Body for Public Sector Higher Education

|

| NAFE | Non-Advanced Further Education

|

| NCVQ | National Council for Vocational Qualifications

|

| OPCS | Office of Population Censuses and Surveys

|

| PCAB | Polytechnics and Colleges Assets Board

|

| PCFC | Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council

|

| PICKUP | Professional, Industrial and Commercial Updating

|

| RACE | Research in Advanced Communications technologies for Europe

|

| SCOTVEC | Scottish Vocational Education Council

|

| SED | Scottish Education Department

|

| SSR | Student: Staff Ratio

|

| STEAC | Scottish Tertiary Education Advisory Council

|

| TVEI | Technical and Vocational Education Initiative

|

| UFC | Universities Funding Council

|

| UGC | University Grants Committee

|

| WAB | Wales Advisory Body for Local Authority Higher Education

|

| YTS | Youth Training Scheme |

[page 42]

ANNEX B

Higher Education Student Numbers: Northern Ireland

1 With the exception of some advanced further education courses mounted in institutions of further education, higher education in Northern Ireland is provided by two universities: The Queen's University Belfast; and the University of Ulster, which was formed in 1984 by the merger of the New University of Ulster and the Ulster Polytechnic.

2 The number of full-time students in higher education in institutions in Northern Ireland has increased by just over 18% between 1979 and 1985. This increase is reflected in the Age Participation Index which has risen from 16.0 in 1980 to 19.6 in 1985. Increases in participation rates have been particularly marked for women, students on science-related courses and mature entrants. The proportion of women among full-time students rose from 46% in 1979 to 49% in 1985, while the proportion of students on science-related courses increased from 35% to 39% over the same period.

3 Future demand for higher education in Northern Ireland was examined in the discussion document Higher Education in Northern Ireland - Future Demand (1985). This set out two variants which projected maximum and minimum levels of student demand. For planning purposes, it also provided a five-year forecast. Against a declining 18 year old population, this envisaged demand increasing from a 1984-85 baseline of 17,290 to 18,200 in 1989-90. This will be reviewed in the light of a survey of student demand now being undertaken. In the meantime, planning figures for 1989-90 have been adjusted to allow enrolments to increase to 18,540, a 4% increase on 1985-86 levels.

[page 43]

ANNEX C

Polytechnics and Colleges to be Transferred from Local Authorities and to Come within the Ambit of the PCFC

*assisted institution; other institutions are maintained by LEAs (see paragraph 4.3)

**includes Hertfordshire CHE student numbers - merging in 1987

***joint LEA assisted/DES grant-aided institution

[page 44]

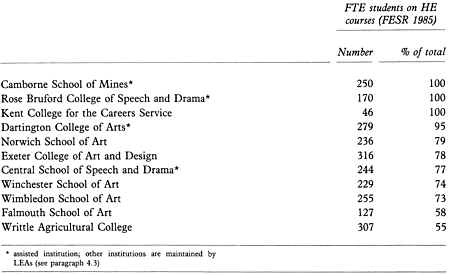

ANNEX D

Institutions with the Choice to Transfer from Local Authorities

Institutions with more than 55% higher education but fewer than 350 full-time equivalent students, having the choice to transfer from local authorities and to come within the ambit of the PCFC

[page 45]

ANNEX E

Voluntary and Other Grant-Aided Colleges to Come within the Ambit of the PCFC

a Voluntary Colleges (17)

Bishop Grosseteste College (Lincoln) Chester CHE

Christ Church College (Canterbury)

College of Ripon & York St John

College of St Mark & St John (Plymouth)

College of St Paul & St Mary (Cheltenham)

Homerton College (Cambridge)

King Alfred's College (Winchester)

La Sainte Union CHE (Southampton)

Liverpool IHE

Newman College (Birmingham)

Roehampton IHE

S Martin's College (Lancaster)

St Mary's College (Twickenham)

Trinity and All Saints College (Leeds)

Westhill College (Birmingham)

Westminster College (Oxford)

b Other Grant-Aided Colleges (8)

Goldsmiths' College*

Harper Adams Agricultural College

Royal Academy of Music

Royal College of Music

Royal College of Nursing

Seale Hayne College**

Shuttleworth Agricultural College

Trinity College of Music

*unless London University accepts Goldsmiths' as a School of the University

**merger with Plymouth Polytechnic under consideration

[page 46]

Map 1: UK Universities

click on the image for a larger version

click on the image for a larger version

[fold-out sheet]

Map 2: Polytechnics and Colleges to come within the Ambit of the PCFC

click on the image for a larger version

click on the image for a larger version