[page 32]

APPENDIX

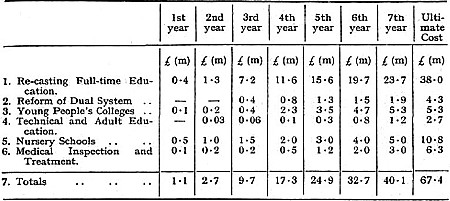

THE FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE PROPOSALS

1. Expenditure on education prior to reforms. In 1938-39 the net expenditure of Local Education Authorities in England and Wales on Elementary and Higher Education was £93.8 million, of which £45.5 million was met from taxes and the remainder, £48.3 million, from rates.

2. Effect of rising costs. These figures do not, however, represent the cost of existing services as it is likely to be immediately before the introduction of any of the proposed reforms. Two adjustments are necessary. The first is an addition to meet the general rise in costs. This rise will vary with the different items of expenditure and an average of 15 per cent has been assumed. The second adjustment relates to the provision of school meals and milk, which have expanded considerably during the war in accordance with Government policy and have recently received a new and powerful stimulus. It is necessary, therefore, to make a further addition to the figures for the year 1938-39 in order to arrive at the expenditure on education in an unreformed post-war year. The total thus reached will be £123 million, of which £66.5 million will be met from taxes and £56.5 million from rates. It is to these figures, representing the assumed expenditure in an unreformed post-war year, that the cost of the proposed reforms dealt with in the following paragraphs must be added.

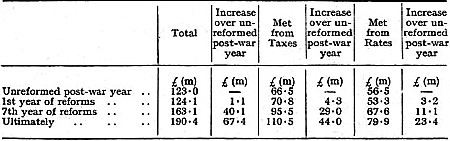

3. Cost of proposed reforms. The proposals for educational reform involve the additional public expenditure shown in Table I below which must be considered in the light of the following factors.

In the first place it is not proposed to introduce any of the proposals until the end of the war in Europe. Thereafter the first step will be to set up the new Local Education Authorities, a process which could not be completed in less than six months. The first substantive step in educational reform, as distinct from the reform of educational machinery, will be the raising of the school leaving age to 15. It will be understood that if this step were taken within a short period after the end of the war before reorganisation is completed, with the primary object of taking children of 14-15 off the labour market, the arrangements for their education would necessarily be of an improvised and makeshift character. If industrial considerations were held to be paramount, the earliest date by which sufficient additional teaching staff could be made available as the result of demobilisation, and accommodation for the extra age-group provided by such temporary measures as hutments and the repair of war damage, would be one year after the new Local Education Authorities come into being.

On the other hand the expansion of Nursery Schools will not present the same difficulties and provision is accordingly included for a substantial and early development of this service.

On these assumptions no material increase in expenditure will begin to accrue until at least 18 months after the end of the war, though there will be some addition in respect of the training of teachers as soon as men and women are released from war service. For the purposes, therefore, of the following tables the first year should be understood as meaning the year in which the leaving age is raised to 15.

The recasting of the system of full-time education and the reform of the dual system will not start to operate until the Local Education Authorities have submitted their development plans and the Board have made their education orders. Apart from expenditure on the acquisition of sites, no expenditure on these reforms, other than that necessitated by raising the school leaving age, will accrue until the third year. The rate of development in that and the succeeding years will depend upon the availability of building labour and materials.

Similarly, the appropriate time for abolishing fees in all secondary schools maintained by Local Education Authorities will come when the Board's education orders have prescribed which schools are to be so maintained. The cost of abolishing fees will not, therefore, show itself until the third year.

The next step for which Local Education Authorities will need to be preparing will be the drawing up of plans for young people's colleges. Substantial expenditure under this head will not accrue until the fourth year.

Although the development of technical and adult education is not included among the matters to be dealt with in the first four year plan, some allowance has been made for preliminary expenditure in respect of technical education.

The expenditure shown in respect of medical inspection and treatment during the first four years is consequential on raising the school leaving age and the institution of young people's colleges, and allows for some preparatory work in anticipation of the date when the provision of medical treatment will be a duty and not, as at present, a power, of Local Education Authorities.

[page 33]

TABLE I

Additional expenditure from public funds attributable to the proposed as compared with unreformed post-war year

4. Revision of Grant System. In order to enable Local Education Authorities generally to play their part in the proposed reforms it is proposed so to modify the present grant formulas that the proportion of the aggregate net expenditure of Local Education Authorities borne by the Exchequer will be increased to 52 per cent in the 1st year and will rise to 55 per cent by the 4th year, the rate of grant to individual Authorities being adjusted, as is the present grant for elementary education, to their varying circumstances. The new grant will apply to expenditure on existing services as well as to expenditure on the proposed educational reforms. Expenditure on school meals and milk will fall outside this formula and will continue to attract the present rates of grant.

Accordingly the total net expenditure in England and Wales on the reformed system of education and the proportions met from taxes and rates respectively would compare with the unreformed post-war position as shown in the following table:

TABLE II

Total expenditure from public funds in England and Wales

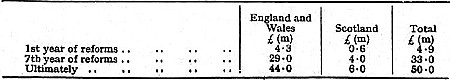

5. Total increased cost for Great Britain. The above figures relate only to England and Wales. The statutory grant to the Education (Scotland) Fund would be automatically increased by 11/80ths of any increase in the cost of education falling on the Exchequer in England and Wales. Thus the total increase in the cost of education to the taxpayer resulting from the increase in costs, from the revision of the grant formula and from the proposed reforms would be:

TABLE III

Increase in Exchequer charge over unreformed post-war year

[page 34]

6. Minor changes proposed. There are four minor changes proposed in the present financial arrangements which have not been included in the above tables. The expenditure involved is, however, relatively inconsiderable and will, therefore, not appreciably affect the earlier calculations:

(a) Boots and clothing. It is proposed to give Local Education Authorities in England and Wales the same powers as Scottish Education Authorities have for the provision of boots and clothing in suitable cases. As this will be a power conferred on Local Education Authorities and not a duty imposed upon them, it is impossible to make a firm estimate of the additional expenditure in respect of it. It is, however, unlikely that for some time to come the new expenditure on this item in any one year would exceed £200,000, of which £110,000 would fall on taxes and £90,000 on rates.

(b) Aid to Research. Provision will be made for aid by the Board to institutions specifically devoted to educational research as distinct from institutions for education. It is also proposed that the rather limited powers of Local Education Authorities under Section 74 of the Education Act, 1921, should be expanded so as to enable them to aid such institutions. No firm estimate can be given of the probable expenditure from public funds as a whole on this development, but it is not considered likely to exceed £100,000 in any one year.

(c) Exemption from Rating. It is proposed to extend to all auxiliary schools, both primary and secondary, the exemption from rating at present enjoyed by non-provided public elementary schools. The result of this will be that auxiliary secondary schools of grammar school or technical school type as well as those schools of modern school type will enjoy this exemption. The financial effect will be that since rates will not have to be paid on the premises of the schools the cost to Local Education Authorities and Governors will be reduced. It is difficult to frame a firm estimate of the financial effect upon the Board's Vote, but it may be expected to relieve the Exchequer of some £50,000 a year.

(d) Endowment Money. It is proposed to repeal Section 41 of the Education Act, 1921. The effect will be that the income of certain school endowments which under that Section is payable to Local Education Authorities for application as therein provided will cease to be so payable. Steps will be taken by means of amending schemes to make the income available for other purposes. The amount of income paid to Local Education Authorities under Section 41 was of the order of £16,000 in the last years for which figures are available.

Similarly, in the case of grammar schools, the income from endowment which is at present available for educational maintenance will cease to be so available in the case of controlled or aided schools, where the cost of educational maintenance will fall wholly on the Local Education Authority. It is estimated that the consequential loss to Authorities will be of the order of £150,000 a year, 55 per cent of which will be met by Exchequer grant.

7. Raising the school leaving age to 16. It is estimated that the gross cost of raising the school leaving age from 15 to 16 would, when it became fully operative, amount to £8.95 million, of which £4.9 million would fall upon the Exchequer. To the latter figure should be added £0.7 million in respect of Scotland.

It is not easy to say whether any compensating saving will result from the fact that, when that step is taken, the period of attendance at young people's colleges will become two years instead of three. On the one hand reduced numbers in attendance would, in the absence of any counteracting factor, reduce the running costs. On the other hand, it may well be that experience of the advantages of day-time attendance of young employees will result in the period of attendance being increased beyond one day a week, whether on a voluntary or a statutory basis.