APPENDIX V

TEACHING PRACTICE

Explanatory note circulated by a college Principal to the head teachers of practising schools in his area (see page 61).

These notes which are the outcome of many years' experiment and experience in more than one training institution have been prepared for circulation to the practising schools in the hope that they may serve to give a brief summary of the general lines on which the students have been instructed in preparation for their practice and to indicate some of the points to which we attach importance.

We consider that the purpose of Teaching Practice is to afford opportunity for -

(1) Practice in actual teaching;

(2) Observing the work and organisation of the school as a whole;

(3) Studying the methods of teaching particular subjects.

We hope that during the period of practice, students will, as far as possible, be treated as members of the school staff. We expect them to abide by the rules and customs of the school (and of its staff room), to share in routine duties such as playground

[page 156]

supervision and to take part in general school activities, including so far as practicable such corporate activities as may take place out of school hours. We shall impress on them that they are guests of the school and that they owe it both courtesy and consideration. We expect them to attend for the whole of the school day unless specifically excused by the Head Teacher or prevented by travelling difficulties. Unless considerations of conscience are involved we urge students to take part in the morning assembly and in the teaching of Religious Knowledge.

The amount of teaching done by a student will at first be small and will increase progressively. The underlying principle is that students should not teach more than they can thoroughly prepare. Hence we suggest that in the first two or three days no teaching should be done and for the remainder of the first week one or two lessons a day should be taught. In the second week an average of two or three lessons a day would be normal and in subsequent weeks the student should work up to a maximum of half to two thirds of the full teaching time-table. Except for one free period a day the rest of the student's time should be spent in definitely allocated observation. We hope that Head Teachers will use their discretion in deciding whether a student who has already had some teaching experience, should work rapidly up to the suggested maximum of teaching. We feel very strongly that it is the quality of the practice that matters rather than mere quantity of lessons taught.

Particularly in the first period of practice we hope that all students will be given practice in teaching the fundamental subjects - English and Arithmetic. In addition they should be afforded opportunity for teaching the subject or subjects in which they are specially interested or for which they are specially qualified. In the later periods of practice more emphasis will be laid on specialisation without neglecting the fundamental subjects.

It will probably be found most convenient and we think it best for a student to be attached permanently to one class and to teach that class the fundamental subjects. For other subjects it will be helpful for the student to observe and teach other classes in addition.

We expect students to secure good discipline by:

(1) Good teaching - which interests the children.

(2) Efficient classroom administration which prevents opportunities for disorder. Hence we shall expect them to note and imitate the exact procedure adopted for such routine matters as, for example, giving out books, etc. Occasion for the use of some kind of

[page 157]

punishment may inevitably arise and students will be instructed to find out exactly what powers are at their disposal in a particular school. It will be emphasised that in no circumstances whatever will any form of corporal punishment be administered by a student.

Instructions have been given that a full record of the practice is to be made in the note-books under three main headings:

(1) For all prepared lessons, notes must be written beforehand, preferably a clear day ahead.

(2) A record is to be kept of lessons observed but it is not necessary to describe every lesson in detail.

(3) A brief diary is to be kept showing how each period of the day has been spent.

For the student himself the systematic making of notes is a means of ensuring the thorough preparation of lessons and of compiling a useful record of experiments, records and comments. For the supervisor the note-book is a valuable guide to the quality of the student's preparation and his grasp of the relation of one lesson to others and it indicates the lines on which the student is planning his work as a whole. The note-book is open to inspection by the Head Teacher and Staff of the school and we hope they will enter constructive comments and suggestions on lessons taught by students and also from time to time direct the student's attention to important points of technique in lessons they observe.

No one set form of notes applicable to all lessons has been given to the students but general headings have been given and certain points stressed, e.g.

(1) The preparation of a lesson involves more than a knowledge of the subject matter.

(2) Notes are inadequate unless they indicate the orderly development of the lesson in some detail, including for example, key questions to be asked and the use to be made of text-book, blackboard, illustrations, the planning of the pupils' practical or written work.

(3) It is a good self-discipline, without which the work loses precision and vigour, to define the precise aim and purpose of a lesson as distinct from its subject and title.

(4) The pupils' activities and opportunities for co-operation should be planned and indicated as well as the teacher's part in the work.

(5) The work accomplished should be summarised (preferably by the pupils or at least with their co-operation)

[page 158]

at convenient intervals. The lines of such summarising should be indicated in the notes. Although a unit of learning may occupy more than one school period, it is unwise to allow a period to pass without a summary, which should also be a means of testing the learning that has been done.

(6) Lessons should be prepared far enough in advance to ensure the planning of the relation between the lessons of a series and to give time for the assembly of the necessary materials.

Notes of lessons observed should pay particular attention to the general principles of method and to such points as - methods of questioning, connection with previous lessons, supervision of practical work, blackboard work and the use of illustrations, manipulation of mechanical aids, use of text-books, methods of keeping a balance between the brighter and duller members of a class. More general observation in the school should be directed to retarded classes and the "Craft" approach towards subjects within the classes for backward pupils. It would be most useful for students to be given an opportunity of studying time-tables organisation and allocation of periods to subjects noting the differentiation of time and syllabus for each year and 'stream'. If possible students should also be given an opportunity of paying a visit to the Infants' Department of the school in order to gain some idea of the continuous process of Education.

It would be very helpful if the Head Teacher could find time to give the students a talk on the organisation and work of the school, its site, buildings and equipment and also direct their attention to a consideration of the school as part of its geographical and social environment, since the handling of work in school must depend very largely upon the conditions under which the children live.

There are two final points. While at first it is to be expected that a member of the staff will always be present while a student is teaching it is hoped that when the student has settled down he will be left on his own for gradually increasing periods. Secondly, we feel that some correction and assessment of written work should be undertaken by students. It would be helpful if the Head Teacher or a member of the staff could describe and explain the methods followed in the school and then allocate some part of the written work of one of the classes to the student.

[page 159]

APPENDIX VI

STATISTICAL TABLES VIII-XIII

The following tables analyse the records of the great majority of the accepted candidates under a number of headings. It has not been possible to cover quite all the records, and the totals therefore do not agree exactly with those given in Tables ill and IV and at the beginning of Chapter 7.

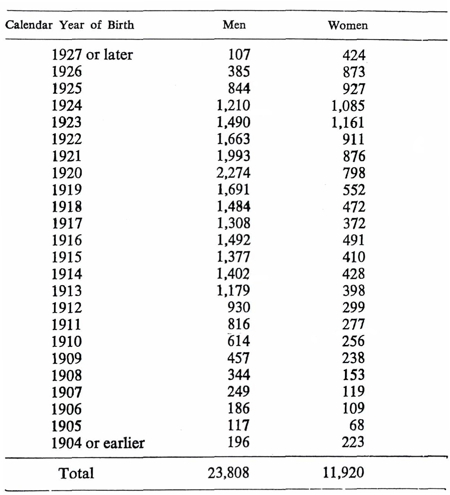

TABLE VIII

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

ANALYSIS BY AGE

[page 160]

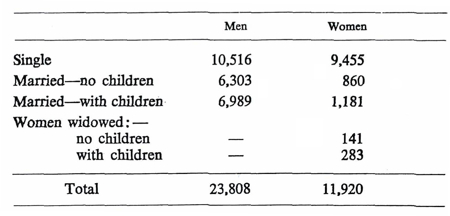

TABLE IX

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

ANALYSIS BY MARITAL CONDITION

[page 161]

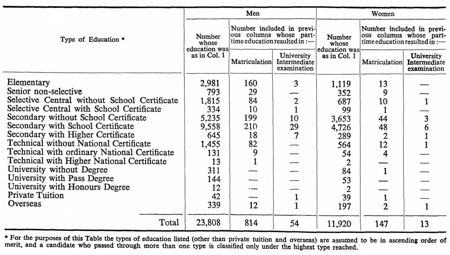

TABLE X

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

ANALYSIS BY PREVIOUS EDUCATION

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 162]

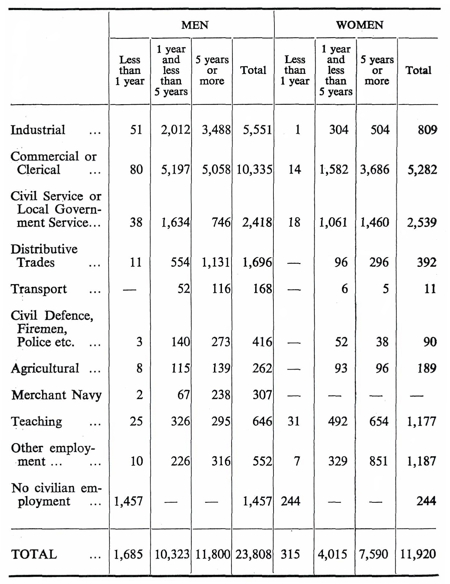

TABLE XI

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

ANALYSIS BY PREVIOUS EMPLOYMENT

[page 163]

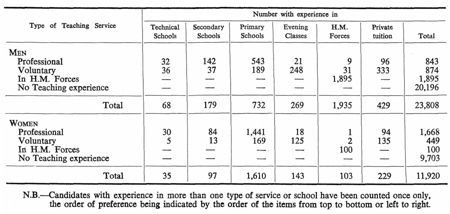

TABLE XII

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

ANALYSIS BY PREVIOUS TEACHING EXPERIENCE AT TIME OF APPLICATION

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 164]

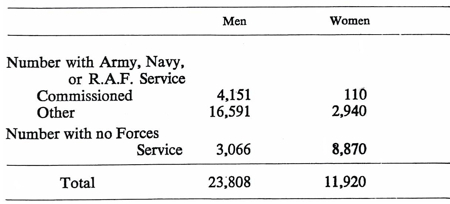

TABLE XIII

ACCEPTED CANDIDATES (LESS WITHDRAWALS)

CLASSIFICATION BY WAR SERVICE