[page 93]

Appendix 7 Bibliography to supplement Chapter 3

We begin by proposing some books with very wide coverage as an orientation to the study of language. (In all cases, date of publication refers to the most recent edition.)

Bolinger, D. L. and Sears, D. A. (1981) Aspects of language Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Hawkins, E. (1987) Awareness of language: An introduction Cambridge University Press

Quirk, R. (1968) Use of English Longman

Yule, G. (1985) Study of language: An introduction Cambridge University Press

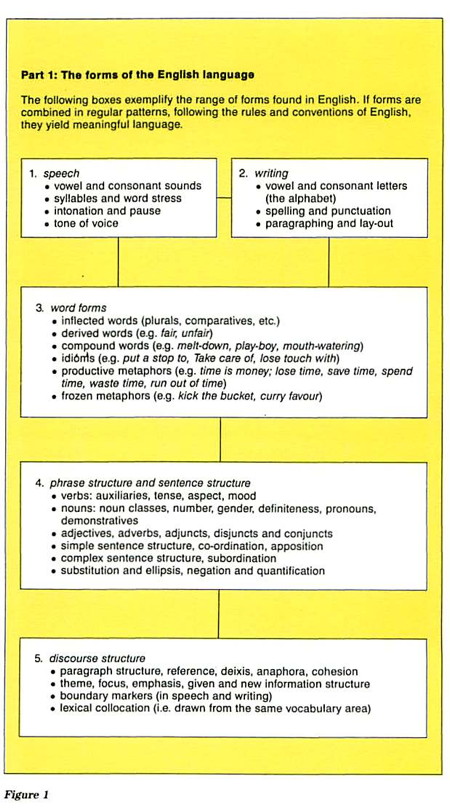

Figure 1: Forms of language

Figure 1 Box 1

Brazil, D., Coulthard, M. and Johns, C. (1980) Discourse, intonation and language teaching Longman

Brown, G. (1977) Listening to spoken English Longman

Crystal, D. (1975) English tone of voice: Essays in intonation, prosody and paralanguage Edward Arnold

Fudge, E. C. (1984) English word stress Allen and Unwin

Gimson, A. C. (1980) Introduction to the pronunciation of English Edward Arnold

O'Connor, J. D. (1973) Phonetics Penguin

Quirk, R. and Greenbaum, S. (1973) University grammar of English Longman

Turner, G. W. (1973) Stylistics Penguin, ch. 2

Wells, J. C. (1982) Accents of English Cambridge University Press (3 vols.)

Figure 1 Box 2

Albrow, K. H. (1972) The English writing system: Notes towards a description Schools Council: Longman

Baugh, A. C. and Cable, T. (1978) History of the English language Routledge and Kegan Paul

Diringer; D. (1962) Writing Thames and Hudson

Frith, U. (ed.) (1980) Cognitive processes in spelling Academic Press

Gelb, I. J. (1952) Study of writing University of Chicago Press

Halliday, M. A. K. (1985) Spoken and written language Deakin University Press

Jarman, C. (1979) The development of handwriting skills Blackwell

Perera, K. (1984) Children's writing and reading: Analysing classroom language Blackwell

Sampson, G. (1985) Writing systems Hutchinson

Scragg, D. G. (1975) History of English spelling Manchester University Press

Stubbs, M. (1980) Language and literacy: The sociolinguistics of reading and writing Routledge and Kegan Paul

Venezky, R. L. (1970) The structure of English orthography Mouton

Figure 1 Box 3

Adams, V. (1976) Introduction to modern English word formation Longman

Aitchison, J. (1987) Words in the mind: An introduction to the mental lexicon Blackwell

Allan, K. (1986) Linguistic meaning Routledge and Kegan Paul (2 vols.)

Bauer, L. (1983) English word-formation Cambridge University Press

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (1988) Vocabulary and language learning Longman

[page 94]

Cruse, D. A. (1986) Lexical semantics Cambridge University Press

Gairns, R. and Redman, S. (1986) Working with words: Guide to teaching and learning vocabulary Cambridge University Press

Hurford, J. R. and Heasley, B. (1983) Semantics: A coursebook Cambridge University Press

Ilson, R. (ed.) (1985) Dictionaries, lexicography and language learning Pergamon Press

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980) Metaphors we live by University of Chicago Press

Leach, G. (1974) Semantics Penguin

Lyons, J. (1977) Semantics Cambridge University Press, vols.1 and 2

Matthews, P. H. (1974) Morphology: Introduction to the theory of word structure Cambridge University Press

Ortony, A. (ed.) (1979) Metaphor and thought Cambridge University Press

Palmer, F. R. (1981) Semantics: A new outline Cambridge University Press

Quirk, R. and Greenbaum, S. (1973) University grammar of English Longman

Figure 1 Box 4

Allerton, D. J. (1979) Essentials of grammatical theory: A consensus view of syntax and morphology Routledge and Kegan Paul

Crystal, D. (1988) The English language Penguin

Gannon, P. and Czerniewska, P. (1980) Using linguistics: An educational focus Edward Arnold

Leech, G. (1982) English grammar for today: New introduction Macmillan

Leech, G. N. (1972) Meaning and the English verb Longman

Leech, G. N. and Svartvik, J. (1975) Communicative grammar of English Longman

Palmer, F. (1988 forthcoming) The English verb Longman

Perera, K. (1984) Children's writing and reading: Analysing classroom language Blackwell, ch. 2

Quirk, R. and Greenbaum, S. (1973) University grammar of English Longman

Winter, E. (1982) Towards a contextual grammar of English Allen and Unwin

Young, D. J. (1984) Introducing English grammar Hutchinson Education

Figure 1 Box 5

Allan, K. (1986) Linguistic meaning Routledge and Kegan Paul (2 vols.)

Brown, G. and Yule, G. (1983) Discourse analysis Cambridge University Press

De Beaugrande, R. A. and Dressler, W. U. (1981) Introduction to text linguistics Longman

Goffman, E. (1981) Forms of talk Blackwell

Gumperz, J. J. (1982) Discourse strategies Cambridge University Press

Halliday, M. A. K. and Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English Longman

Hoey, M. (1983) On the surface of discourse Allen and Unwin

Levinson, S. C. (1983) Pragmatics Cambridge University Press

Quirk, R. (1987) Words at work: Lectures on textual structure Longman

Quirk, R. and Greenbaum, S. (1973) University grammar of English Longman

Stubbs, M. (1983) Discourse analysis: The sociolinguistic analysis of natural language Blackwell

van Dijk, Teun A. (1980) Text and context: Explorations in the semantics and pragmatics of discourse Longman

Widdowson, H. G. (1983) Learning purpose and language use Oxford University Press

[page 95]

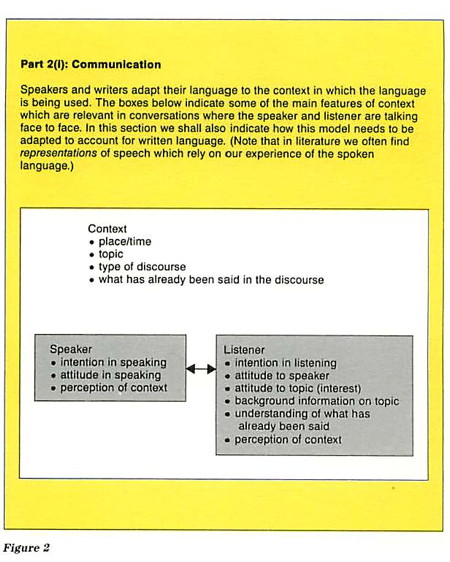

Figures 2 and 3: Communication and comprehension

Figure 2: Communication

Brown, P. and Levinson, S. C. (1987) Politeness Cambridge University Press

Bygate, M. (1987) Speaking Oxford University Press

Grice, P. (1975) 'Logic and conversation' in P. Cole and J. L. Morgan (eds.) Syntax and semantics vol.3: Speech acts Academic Press

Gumperz, J. J. (1982) Discourse strategies Cambridge University Press

Hudson, R. A. (1980) Sociolinguistics Cambridge University Press

Kress, G. (1982) Learning to write Routledge and Kegan Paul

Lyons, J. (1981) Language, meaning and context Fontana

Milroy, J. and Milroy, L. (1985) Authority in language: Investigating language standardisation and prescription Routledge and Kegan Paul

Montgomery, M. (1985) Introduction to language and society Methuen

O'Donnell. W. R. and Todd, L. (1980) Variety in contemporary English Allen and Unwin

Ong, W. J. (1982) Orality and literacy Methuen

Richards, J. C. and Schmidt, R. W. (eds.) (1983) Language and communication Longman

Saville-Troike, M. (1982) Ethnography of communication Blackwell

Shaughnessy, M. (1977) Errors and expectations Oxford University Press

Sinclair, J. McH. and Brazil, D. (1982) Teacher talk Oxford University Press

Smith, F. (1982) Writing and the writer Heinemann

Wardhaugh, R. (1985) How conversation works Blackwell

Widdowson, H. G. (1978) Teaching language as communication Oxford University Press

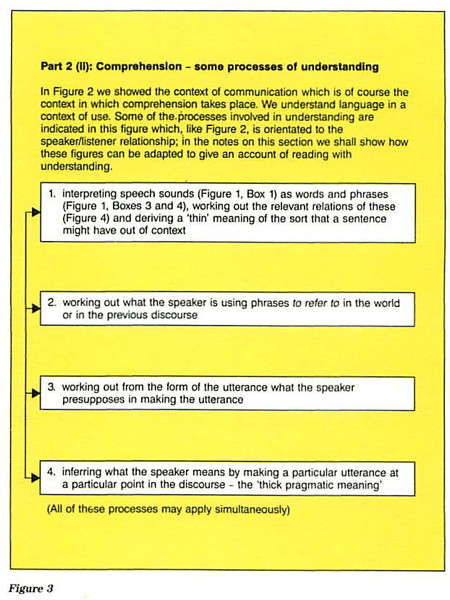

Figure 3: Comprehension

Aitchison, J. (1976) Articulate mammal: Introduction to psycholinguistics Hutchinson Education

Allan, K. (1986) Linguistic meaning Routledge and Kegan Paul (2 vols.)

Anderson, A. and Lynch, A. (1988 forthcoming) Listening Oxford University Press

Brown, G. and Yule, G. (1983) Discourse analysis Cambridge University Press

Carter, R. (ed.) (1982) Language and literature: An introductory reader in stylistics Allen and Unwin

Clark, H. H. and Clark, E. V. (1977) Psychology and language: Introduction to psycholinguistics Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Cluysenaar, A. A. A. (1976) Introduction to literary stylistics Batsford

Edwards, D. and Mercer, N. (1987) Common knowledge: The development of understanding in the classroom Methuen

Garnham, A. (1985) Psycholinguistics Methuen

Harrison, C. (1980) Readability in the classroom Cambridge University Press

Leech, G. N. and Short, M. H. (1981) Style in fiction: A linguistic introduction to English fictional prose Longman

Levinson, S. C. (1983) Pragmatics Cambridge University Press

Lunzer, E. and Gardner, K. The effective use of reading Heinemann Educational

Sanford, A. J. and Garrod, S. C. (1981) Understanding written language: Exploration of comprehension beyond the sentence John Wiley

Sperber, D. and Wilson, D. (1986) Relevance: Communication and cognition Blackwell

Strickland, G. (1981) Structuralism or criticisms: Thoughts on how we read Cambridge University Press

Stubbs, M. (1983) Discourse analysis: The sociolinguistic analysis of natural language Blackwell

Widdowson, H. G. (1975) Stylistics and the teaching of literature Longman

[page 96]

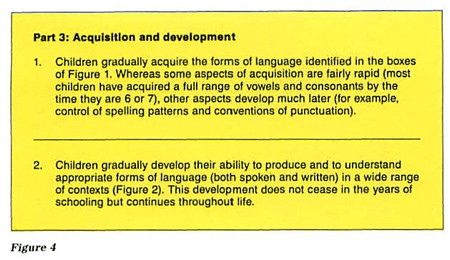

Figure 4: Language acquisition and development

Aitchison, J. (1976) Articulate mammal: Introduction to psycholinguistics Hutchinson Education

Brice-Heath, S. (1983) Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classrooms Cambridge University Press

Brown, R. (1974) First language: Early stages Allen and Unwin

Bruner, J. S. (1975) 'Language as an instrument of thought' in Davies, A. (ed.) Problems of language and learning Heinemann Educational

Clark, H. H. and Clark, E. V. (1977) Psychology and language: Introduction to psycholinguistics Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Dale, P. S. (1976) Language development: Structure and function Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Davies, A. (ed.) (1977) Language and learning in early childhood Heinemann Educational

Donaldson, M. (1984) Children's minds Fontana

Donaldson, Morag (1986) Children's explanations: A psycholinguistic study Cambridge University Press

Durkin, K. (1986) Language development in the school years Croom Helm

Edwards, J. R. (1979) Language and disadvantage Edward Arnold

Fletcher, P. J. and Garman, M. (eds.) (1979) Language acquisition: Studies in first language development Cambridge University Press

Gordon, J. (1981) Verbal defect: A critique Croom Helm

Halliday, M. A. K. (1975) Learning how to mean Edward Arnold

Luria, A. R. and Yudovich, F. Ia. (1978) Speech and the development of mental processes in the child Penguin

Olson, D. R., Torrance, N. and Hildyard, A. (1985) Literacy, language and learning: The nature and consequences of reading and writing Cambridge University Press

Perera, K. (1984) Children's writing and reading: Analysing classroom language Blackwell

Rogers, S. (ed.) (1976) They don't speak our language: Essays on the language world of children and adolescents Edward Arnold

Romaine, S. (1984) Language of children and adolescents: The acquisition of communicative competence Blackwell

Tizard, B. and Hughes, M. (1984) Young children learning: Talking and thinking at home and at school Fontana

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962) Thought and language Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press

Wells, G. (1985) Language Development in the pre-school years Cambridge University Press

Wells, G. (1987) The meaning makers Hodder and Stoughton

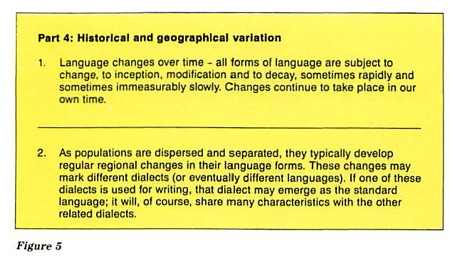

Figure 5: Geographical and historical variation

Geographical variation

Bell, R. T. (1976) Sociolinguistics: Goals, approaches and problems Batsford

Dittmar, N. (1976) Sociolinguistics: A critical survey of theory and application Edward Arnold

Edwards, V. (1979) The West Indian language issue in British schools: Challenges and responses Routledge and Kegan Paul

Hudson, R. A. (1980) Sociolinguistics Cambridge University Press

Hughes, A. and Trudgill, P. (1979) English accents and dialects Edward Arnold

Kachru, B. B. (1986) Alchemy of English Pergamon Press

Linguistic Minorities Project (1983) Linguistic minorities in England Heinemann Educational

Linguistic Minorities Project (1985) Other languages of England Routledge and Kegan Paul

Montgomery, M. (1985) Introduction to language and society Methuen

[page 97]

Quirk, R. and Widdowson, H. G. (eds.) (1985) English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literature Cambridge University Press

Rosen, H. and Burgess, T. (1980) Languages and dialects in London schoolchildren: An investigation Ward Lock Educational

Suttcliffe, D. (1983) British Black English Blackwell

Suttcliffe, D. and Wong, A. (eds.) (1986) Language of the Black experience Blackwell

Trudgill, P. (1975) Accent, dialect and the school Edward Arnold

Trudgill. P. (ed.) (1984) Language in the British Isles Cambridge University Press

Wakelin, M. F. (1977) English dialects: An introduction Athlone Press

Wakelin, M. F. (1985) English dialects Shire Publications

Historical variation

Aitchison, J. (1986) Language change: Progress or decay? Fontana

Baugh, A. C. and Cable, T. (1978) History of the English language Routledge and Kegan Paul

Greenbaum, S. (1984) The English language today Pergamon Press

Jenkins, C. (1980) Language links: The European family of languages Harrap

Lass, R. (1987) The shape of English: Structure and history Dent

Lockwood, W. B. (1975) Languages of the British Isles past and present Deutsch

Scragg, D. G. (1975) History of English spelling Manchester University Press

Strang, B. M. H. (1974) History of English Methuen

Tucker, S. I. (1961) English examined: Two centuries of comment on the mother-tongue Cambridge University Press

[page 99]

Appendix 8 The model in summary form

[The following diagrams were presented on a fold-out sheet attached inside the back cover.]