[page 3]

Part 1

1. The extent of the survey

1.1 To provide a range in the sample of both size of authority and type of geographical area served visits were paid to 10 local authorities; 4 were non-metropolitan counties, 4 metropolitan districts and 2 were outer London boroughs.

1.2 In all, 61 nurseries in various settings were visited. Further details of their size and composition are provided in the appendices, but the list included:

38 nursery units attached to primary schools.

1 under-fives unit attached to a primary school, the joint responsibility of Education and Social Service departments.

13 nursery schools.

9 nursery classes in special schools for children who are physically handicapped (6), mentally handicapped (1), delicate (1) and with hearing impairment (1). One school was limited to under-fives.*

Four nursery units and one nursery school had units for children with special educational needs attached either to them or to their main school and included children from these in their nurseries. One special unit provided for physically handicapped children, one for children with speech and language disorders and 3 others for those with hearing impairment.

One education authority had made a variety of joint arrangements with its social service department. Apart from the combined under-fives unit, already mentioned, one nursery class in the survey was joined during morning sessions by 6 children from a day nursery and in another instance, a teacher from the school staff working in the nearby day nursery accompanied her group of children to the nursery class on 2 occasions each week. A special school in the

*Although no longer in use following the implementation of 1981 Education Act, the terms used at the time of the visits to describe the categories of handicap, for which the special schools catered, have been retained.

[page 4]

same authority provided accommodation and a teacher for a jointly organised playgroup to which any child between 3 and 5 years living in the area was eligible for admission.

1.3 Nursery units attached to primary schools generally served their immediate areas. A majority of their children continued their education in the schools to which their nurseries were attached though there were some who transferred to different primary schools at around the age of 5 years.

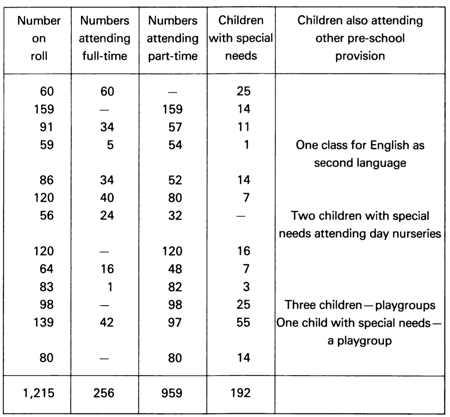

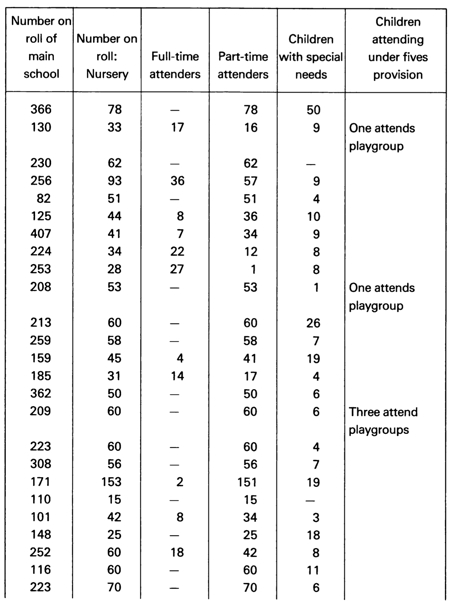

1.4 Pronounced variations were seen in the sizes of primary schools and the nursery units attached to them. The smallest school had 82 children on roll and the largest 407. Numbers of nursery aged children ranged between 15 and 153. All provided part-time places and almost half of them full-time places (see Appendix 2); in some instances full-time places, as in nursery schools, were arranged especially for those with special educational needs. Where teachers had established their own criteria for selection of full-time attenders, these included the age of the child, the degree of social need, parental choice and availability of nursery places. The majority of children to be found in the ordinary nurseries included in the survey attended part of the day; 1 in 7 attended both sessions. However, the number of full-time attenders in the 13 nursery schools visited equalled that of those attending the much larger number of nursery units. (See Appendices 1 and 2.)

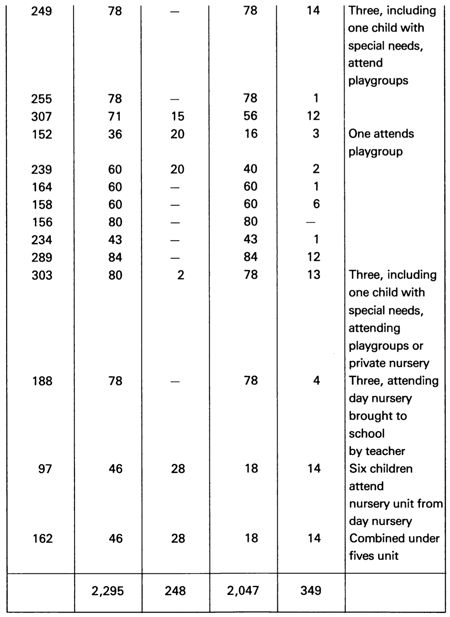

1.5 The nursery schools varied in size from the smallest with 56 children on roll, some attending for whole days and others for one session per day, to the largest with 159 part-time attenders. There were several kinds of arrangement made to meet children's or families' needs. One nursery school provided only full-time places and 4 limited their provision to part-time places. The rest admitted children to both full and part-time places; in one or two instances only those with special educational needs attended both daily session. (See Appendix 1.)

1.6 Although in theory some ordinary nursery schools served the whole or a section of an authority, in practice their catchment areas were smaller than those of the special schools and most children lived within walking distance of them. Only in cases of exceptional difficulty was transport provided by education or social service departments. For example, a child with Down's Syndrome and one whose parents were deaf were among those for whom transport was provided.

[page 5]

1.7 Many of the nursery schools and units reported that the social problems they faced were great and increasing. However, in many schools there were children from a range of social conditions whose parents tried to support the nursery and were concerned about their children's progress. Some of the children admitted to the combined under-fives unit were not there because of poor social circumstances; some mothers required extended day care for their children so that they could take employment; others accepted places under social services provision, even though payment had to be made, until vacancies occurred in the places allocated by the education authority. Not all children attended every day of the week.

1.8 The nursery classes in special schools served the whole of the borough or area of the county in which they were situated and occasionally accepted children from neighbouring authorities for whom this was the most convenient or appropriate school. Children were usually transported by taxi, mini-bus or ambulance provided by the authority. One school in a non-metropolitan area reported that travelling time for some children could be as long as an hour and 40 minutes. In order to overcome the problem of travelling long distances, some children in 2 schools were either fostered with local families or were boarded in the schools.

1.9 Special schools by their nature tend to be small. Those included in the survey ranged in size from 19 to 126 children on roll. All, except one, were all-age schools with nursery classes. Some children in nursery classes were over the age of 5 and were considered outside the scope of this exercise. (See Appendix 3). Part-time attendance at these schools was unusual and often amounted to a reduced number of days per week rather than one of 2 daily sessions as the latter presented difficulties to those arranging transport. It was noted, however, that these difficulties had been overcome in some instances where half-day attendance was more appropriate for a child.

1.10 29 children, five of them children with special educational needs, also attended a different kind of under-fives provision and almost every nursery had other under-fives provision in its area. Groups for mothers and toddlers met in the vicinity of 3 of the nurseries. In addition, in the exceptional nursery run jointly by a social services and an education department a greater proportion, some 40 per cent of children, were able to receive full-day care during the whole of the year. Although there were no links between the different forms of provision, or only tentative ones in some areas, there were many examples of

[page 6]

close liaison and a high degree of cooperation between them. Members of staff had exchanged visits; others had invited playgroup leaders and children to social functions and open days as well as to see the nursery's daily routine activities. Some nursery staff had helped to organise courses for playgroup leaders. Often, when children were about to transfer from playgroups to a nursery school or unit, there was an exchange of information. Several parents of nursery children were themselves leaders of playgroups and this made communication more likely. Three schools had donated surplus equipment to local playgroups. Relationships with day nurseries were less well developed except where links were encouraged, especially in one authority, at senior officer level. There were no instances of curricular discussions except where courses had been arranged jointly for nursery and day nursery staff and in the combined under-fives unit where all members of the team were closely involved in every aspect of its work.

[page 7]

2. The educational environment

2.1 More than half of the nursery schools had appropriate accommodation and were unlikely to require adaptations for children with special educational needs. Such premises included large but easily supervised playrooms, small rooms for individual or group work and easy access to outdoor play areas. Some had interesting features, for example, raised or tiered sections, open plan arrangements or observation rooms which enabled members of staff to use the building flexibly and to enhance their work with children with differing needs. Four other nursery schools had potentially suitable premises but were failing to use them effectively; in these there was poor arrangement of furniture, cluttered equipment which restricted children's movement, staff rooms unused when they could have been used for withdrawal of individuals or small groups.

2.2 Almost all nursery units were housed at least adequately, some in very good accommodation. Some were purpose built, others had been converted from infants' classrooms; one of these had required no alterations until the admission of children with certain disabilities when the need for adaptations was revealed. Because very few heavily physically handicapped children had so far been admitted to the nursery units, potential shortcomings in accommodation had not yet revealed themselves. However, steps, a split level playroom or lack of ramps were unlikely to prohibit the admission of physically handicapped children of this age, size and weight.

2.3 Although most nursery schools and units had grassed and paved outside areas, some were poorly provided in this respect. One unit had only a small, bleak playground with inadequate and insufficient equipment. Another had a large enough grassed area but regrettably the only hard surface was the road leading to the nursery used by service vehicles. Another had a dark, bleak playground subject to high winds, repeated vandalism and with not a tree or blade of grass in sight.

2.4 Several of the nursery units were detached from main buildings and so remote that the level of support was less than desirable.

2.5 The great majority of ordinary nurseries, whether schools or units, were well able to provide the kind of stimulating environment which is conducive to

[page 8]

sound development and learning. One in two were of a very high quality; they were all nursery units. For example:

Nursery 1 had a large play area and 2 recesses. The staffroom and one other small room were used by staff for story telling and music. While one recess was used for domestic play, the other was primarily used for play with a variety of bricks and planks. In the larger area, arrangements were made for wet and messy activities, a quiet book corner and table top tasks. Water play took place in the cloakroom entrance. Well presented displays were aptly sited and children kept well informed about them.

In Nursery 2 a large open plan area surrounded 2 toilet blocks and all equipment, materials and activities arranged on 4 sides were available to all children. The provision included:

a book area with seating and low shelves well stocked

a utility room where children's clothes were cleaned or dried

an enclosed room used currently for active, physical play

an area containing water play equipment, woodwork bench and dough table

a pet area - with gerbils, guinea pig, stick insects, rabbit and budgerigar

an enclosed room used as a playhouse with full-sized bed and furniture

a brick building area complete with carpet

a wet area containing wet and dry sand and clay

a quiet room for music sessions and with an open domestic play section

an outside verandah containing a large sand pit

an outdoor area with a good proportion of grass, brick and concrete surfaces, landscaped garden, climbing frames and wheeled toys.

The one room in Nursery 3 containing artistically arranged displays of fabrics, artefacts, natural objects and books was subdivided to provide a quiet area. The smaller section, carpeted, was equipped partly as a book corner and partly as a science section with wheels, pulleys, camera, magnifying glasses, magnets etc. The larger section included clearly defined spaces for living things, a shop with imitation cakes, till and tables arranged as for a cafe, table top activities, large and small bricks and a home corner with dressing up clothes.

[page 9]

Two rooms made up the accommodation of Nursery 4; one used as a quiet room was carpeted and contained books, piano and tables for sorting, matching, constructional activities etc. The second, a larger room, was arranged for sand and water activities, painting, domestic or hospital play while a space was left for floor play. A section of the room was currently a make-believe office with switchboard, typewriter and calculator. The entrance hall was used for display and one corner was arranged as a spaceship with simple scientific equipment and simple lighting using batteries and bells.

Even though, in some instances there was only one playroom, separate areas had been created with different floor coverings and specific places set up for wet, dirty or noisy play and quiet, restful play. Staffrooms were frequently used for withdrawal or small group activities as well as by visiting support staff. Great credit was due to the members of one nursery class housed in a community centre for their excellent use of less than ideal premises where it was necessary for equipment to be cleared away and stacked daily. It was noted that almost all the nursery schools were not just adequately, but, excellently equipped. A rather smaller proportion of nursery units reached the same standard; but only a small number were seriously deficient. Any shortages, for examples, of simple scientific equipment, or large building bricks, were often caused by a lack of recognition of their importance by the school.

2.6 Two-thirds of the accommodation for under-fives in the special schools was appropriate. Five nurseries were of modern design. Examples of special features or facilities included hydrotherapy pools, below floor level sandpit and pool, one-way screens, withdrawal rooms, ramps and handrails and non-slip floor areas. Special equipment included adapted chairs, special toilet seats or chairs, hand propelled wheeled toys and basic electronic teaching aids. Although other schools had some appropriate features and specialised equipment there were limitations which included lack of any grassed area, very small play areas, no direct access to outdoors, poor lighting and inadequate facilities for changing. One group of children was housed in a Nissen hut. Another group, more fortunate, was housed in a suitably converted house.

2.7 The playrooms in special schools did not always provide the kind of environment described earlier and which was found in so many ordinary nurseries. There was some lack of the order and definition of purpose which is characteristic of the well arranged nursery environment with its distinct wet,

[page 10]

messy, quiet, book, brick building areas. Play equipment was pushed back or folded away, books were not always displayed; horizontal surfaces at appropriately low levels at which children could handle or examine interesting objects were absent. Play materials were not stored in such a way as to promote the independence of those with full or limited mobility. Equipment for large motor activity was sometimes available only in the physiotherapists' room at some distance from the playroom. Rooms, in one or two cases, were untidy and cluttered. The atmosphere in at least one nursery was neither cosy nor intimate, lacking any opportunities for seclusion and escape from the whole group if a child needed it. In contrast 2 nursery classrooms in special schools were comparable with the best of those in ordinary nurseries.

[page 11]

3. Planning the programme

The staff involved

3.1 The most usual arrangement was for both teachers and nursery nurses together to be responsible for programme planning. In a small number of nursery units, the heads of primary schools were also regularly involved in discussion. In three nursery schools heads played only minor parts in day to day planning, leaving the major responsibility to teachers and nursery nurses. There was a tendency for more teachers in nursery units than in nursery schools to plan alone, an arrangement which is more typical of the infant teacher with a classroom helper. In only 2 special schools were there teachers planning alone; elsewhere, in addition to the nursery nurse, physiotherapists, speech therapists, doctor or psychologist might be involved. Other professionals were said to be involved in one or two nursery schools in relation to children with special needs but this was no more than marginally.

3.2 In 2 special schools a commendable degree of cooperation existed between nursery teachers and parents in formulating programmes for individual children; in one school this was solely in the use of Bliss symbols* but in the other, programmes were concerned with wider aspects of development.

The curriculum

3.3 About a third of the nurseries had or, as in 3 authorities, were working towards, a statement of intent about the curriculum. These statements differed in quality. Some were of a general nature providing little support for staff and were more appropriate for providing information to parents of newly admitted children. In other instances, broad aims were set out or a check list was used though by its very nature it said little about content, method or progression.

3.4 On the other hand there were examples of well thought out, documented material. One statement had been prepared by the nursery heads and adviser of

*A system which provides a written means of communication for children with little or no speech.

[page 12]

an authority. It included statements of aims and objectives in physical, emotional, intellectual, social and moral development. Another nursery had produced a guideline with aims and objectives to assist in promoting development in language, physical education, dance, pre-reading and pre-maths. A nursery nurse had collaborated with the school head in the analysis of most nursery activities clearly showing their purpose and value. Where flowcharts were used to advantage as an aid to planning they were linked to what children needed to learn and experience and not only to programme content.

3.5 There were nurseries where, though no written document had been produced, a good deal of attention had been paid to the purpose of activities and to progression in learning. However, where good written documents were produced, the quality and precision of planning were usually more marked.

3.6 In some nurseries, even where educational planning was minimal, there was some daily consultation about which activities and equipment could be prepared with some reference to novelty and change, but in the poorer there was an unchanged daily routine.

3.7 Just under one in 10 of the nurseries, including a larger proportion of the nursery schools than of the nursery units, used staff discussion as a basis for weekly or termly planning of themes embracing several areas of the curriculum and recorded in many instances as flowcharts. For example, the weekly programme of one nursery unit was planned under the headings of Creative Work, Language, Early Mathematical Experience, Topics, Poetry and Music. In a similar number of nurseries, members of staff produced weekly written notes following discussion but in some cases the only areas considered were those described as "structured", ie such tasks as picture and colour matching, tracing, writing, counting and sorting. Others held weekly discussions but with no recording of plans; sometimes it was very apparent that their work was greatly influenced by their discussion. Responsibilities for different areas of the playroom or different activities were often allocated daily or weekly. An example of fruitful planning was seen in one nursery school where a soundly based curriculum guide enabled members of staff to discuss how a chosen topic could be planned to include many and various activities at different levels for younger and older, brighter and less able children. Their planning was presented in the form of flowcharts effective as working documents rather than polished schemes.

[page 13]

Assessment and record-keeping

3.8 On the whole assessment and record-keeping was not systematic; in many of the schools there was no overall policy and staff had not been encouraged to develop one. Differing amounts of attention had been given to this aspect of the work. In 8 out of 10 nurseries members of staff were practising some form of record-keeping though often this was of little use in forward planning. For example, observations were made only infrequently, statements were vague and general, lacking in detail, not cumulative, with only a final report written at the time of the child's transfer to primary school. The focus was frequently directed upon social behaviour. There was a lack of sequence; items of learning which were included were of varying significance; there was no means of comparing different aspects of development in a child and items were poorly grouped. Some nurseries relied solely on their local authority's record cards which were not intended for educational planning and so lacked necessary detail. One authority had given considerable attention to devising a most helpful guide to assessment and record keeping which was to come fully into use later in the year.

3.9 Rarely were any different systems employed in making assessments and recording the progress of children with special educational needs. Such children were identified as having some different needs from under fives generally but careful observation did not always follow and records were often far from satisfactory. For example, in two instances where children with impaired hearing were withdrawn for specialist teaching, progress was recorded only by this teacher and the children's ability to function within the main nursery group was not recorded.

3.10 In this aspect of the work, it was the special school staff who most often showed expertise partly, perhaps, because the problems with which they were dealing were more complex, partly because they were working with fewer children, and possibly because more emphasis has been given to these practices in this particular sector of education. But there were nurseries, both ordinary and special, where sound assessment and record-keeping procedures were in the process of being developed and in about one in six schools efficient systems were already being successfully implemented. These nurseries were most likely to use check lists of developmental items, many along with brief notes on an individual's general progress or with local authority record sheets. Some systems were devised by teachers themselves and others, for example, the

[page 14]

Portage Checklist, the Keele Progress Assessment Guide, and the Croydon Checklist were commercially published or more widely available.

3.11 Generally, observation, assessment and records were most effective when based on published schemes which had been adapted to suit the specific needs of the nursery and staff preferences. The staff in one nursery school completed the Keele Progress Assessment Guide for children after their first term in school and then at six-monthly intervals.

First assessments were made by the nursery nurses and later by the teacher. The authority's record was also completed. The staff of one nursery unit used a system based on one of the commercially produced ones but modified it to suit their own requirements; it was completed for all children one month after entry and again later; all members of staff were involved in making entries. The record was quick to complete, easy to interpret, allowed for additional comment and was used again to support the local authority record. The staff of another nursery school who had similarly developed their own personal method of record-keeping held frequent staff meetings to ensure consistency of interpretation. Their aim was to make an assessment of a child on 3 occasions during his time in the nursery, at the end of the child's first term, towards the end of his first year and before transfer to the primary school. The observations of all staff were taken into account. A profile of each child was also written and passed to the primary school to which each child transferred. For children with special educational needs other procedures might be adopted, for example, for one such child the Portage Guide to Home Teaching system of recording was used and for another a system previously used when the child attended an assessment centre was continued.

3.12 In more than half of the special schools records were thorough and well maintained, covering all areas of child development. One covered all areas of its nursery curriculum viz social behaviour, expressive language, visual skills, tactile skills, pre-writing and number. In a second special school nursery entries were made on language, visual and auditory sequencing, manipulative tasks, pre-number, self-help and, where appropriate, on progress with Bliss symbols. Another checklist was completed weekly and a folder containing children's work was passed to the next class. The practices in a third special school nursery were equally appropriate. Detailed checklists were devised to cover similar areas of development as already listed, including Bliss (see para 3.2) and Makaton sign language, if appropriate, and these were closely linked to the nursery's

[page 15]

written curriculum, against which progress was measured. Three monthly learning goals were defined for individual children and for the group as a whole.

3.13 While records were, in many of the nursery classes in special schools, used as a basis for educational planning this was less likely to be so in nursery schools and units. Where procedures were well devised they were most likely to be used profitably. It was inevitable that any failure to assess systematically and record progress and development tended to reduce the ability to meet the precise needs of children as a group or as individuals. At best, in such a situation, a wide range of activities was made available for children to choose and sample. However, where, as in one nursery school, observations were systematic and record-keeping relevant, gaps in children's development were highlighted. When, therefore, activities were introduced, children were helped towards certain tasks and experiences including sometimes more structured language sessions. In another nursery members of staff were moving towards the application of task analysis to their work in order to meet certain children's educational needs. Some nurseries were anxious to relate the assessment and education of children with special educational needs even though links were not made generally. Members of staff were often seen to be seeking for some way to help a child but, in some instances, with little professional skill in distinguishing the problem before bravely attempting to meet the special educational need. There were, as was stated earlier, nursery schools and units where all children came within the normal range or where those with special educational needs were well able to gain maximum benefit from the range of nursery activities and experiences generally provided. However, with very few exceptions, the same educational provision was made for all children though it was apparent that the experiences could become fully available to some only if special measures were taken.

3.14 Though the staff of nursery classes in special schools showed greater reliance on their records of individual progress as a basis for educational programme planning, there were instances where the poor quality of records or failure to use information positively led to the absence of any strategies for accelerating or encouraging development. Occasionally there was a lack of urgency; children were left at tasks for too long and learning goals were inappropriate. In the nurseries where assessment was multi-disciplinary and where professionals, in addition to teachers and nursery nurses, shared in the process of individual programme planning, education was of a better quality.

[page 16]

3.15 In one such nursery, for example, where there was obvious skill in meeting both the specific needs of any child and those needs he held in common with other under fives, personal and general programmes were soundly based. Each child was observed and his progress measured against a framework of normal child development; a note was made of what he was able or not able to do at a particular time. Each week the teacher selected a task from several areas of learning which were relevant to the child's stage of development and though within his capability were not yet part of his normal behaviour. For instance, the task might be to push a wheeled toy, to transfer an object from one hand to the other, to build a tower of small bricks or to recognise identical pairs of pictures and to point out the differences of pairs. The tasks were analysed and presented in a meaningful sequence of small steps, as in this example:

Stage 1: To find a match for an object shown by the teacher (sample) from 2 alternatives.

Stage 2: To find a match from more than 2 alternatives (objects).

Stage 3: To find a match from 2 alternatives (picture/objects).

Stage 4: To find a match from more than 2 alternatives (picture/object).

Stage 5: To find a match for several samples (picture/picture).

Stage 6: To play with Lotto - large, single pictures; smaller, complex pictures.

Each time the child succeeded he was rewarded immediately and consistently, usually with a word of encouragement. Progress was constantly evaluated so that the teaching could be adapted and the task altered as necessary or a new one selected. But there were also opportunities for free play within a carefully planned environment so that a good balance was maintained between individual and group, between precisely programmed and less structured activities, a feature not found in every special school nursery class.

[page 17]

4. The quality of the education

4.1 The width and balance of different types of activities and opportunities provided during a daily session were appropriate in most of the nursery schools and in a slightly smaller proportion of nursery units attached to primary schools. There were a few nurseries, both schools and units, where programmes were outstandingly good.

4.2 All areas of the curriculum were given appropriate attention. Activities to encourage language development included stories, poetry and rhymes and opportunities for extending the children's range of language, knowledge, understanding and imagination. Enjoyment of books was fostered. When appropriate, opportunities for mastering reading were made through an informal approach to the written word. Listening skills were not neglected. Early mathematical experiences and ideas were developed through play with, for example, blocks, woodwork, junk-modelling, outdoor equipment, see-saw, sorting and grading apparatus. Children were given, for instance, experiences of different shapes, sizes, relationships and of balance. The children's attention was drawn to the world around them; living and growing things, weather and seasons were observed. Early scientific experiences included a developing knowledge of the properties of certain materials. Children were made aware of how different people contribute to our daily lives. Visits were also made to the immediate locality and visits were received from people in the local community. In order to develop coordination and cooperative attitudes and to provide a medium for the expression of feelings and ideas, a wide range of natural and man-made materials to give experience of colour, texture, size, shape and weight was provided. Creative and constructive materials encouraged imaginative play including role play. Children listened to sounds which helped towards perception and discrimination between them. Awareness of intensity and pitch and the beginnings of music making were encouraged. There were opportunities for gross and fine movement and for agility and meeting challenges in the use of, for example, climbing equipment or in movement to music and singing games. The better programmes allowed ample time for children to become deeply involved in play and to develop it fully. The absence of excessive routine left children undisturbed at crucial moments. Differing forms of grouping allowed children to opt for or against joining certain arrangements.

[page 18]

4.3 Those which were less successful had the following characteristics:

excessive concentration on pre-reading, writing and number which was detached from the practical experience already forming an integral part of the play provision

strict timetabling and fragmentation of the session which restricted the full development of play or, on the other hand, the neglect of any order in the session

too many sedentary occupations

under-provision for creative and imaginative play

too much importance given to routine tasks carried out by the whole group of children so that some spent a great deal of time waiting for others to complete a task before they were permitted to begin a new activity.

4.4 Although there seemed a widely held assumption that a single nursery programme would accommodate the needs of all children in ordinary nurseries, there were a few teachers who rightly decided either that they needed to modify their general arrangements or that the proportion of direct adult contact with children with special educational needs must be greater than with other children. In a few nurseries this was facilitated by the introduction of withdrawal arrangements or by an adult helping a particular child wherever he played. In hardly any of the nurseries visited did such an arrangement significantly deprive the other children of teacher time. Where it did so, the teacher was either deployed solely with those withdrawn or deployed in this way for a large proportion of time.

4.5 In a few instances where adverse effects were noted, the children who required an undue proportion of the adult attention available from current staffing ratios were, as to be expected, children who were severely handicapped. In one or two nurseries, a generous overall staffing ratio reduced such an effect. It had been arranged, in one instance, for a severely handicapped child to be admitted only when her mother agreed to accompany her to school and remain with her throughout each daily session.

4.6 A nursery nurse had been employed in one nursery to work solely with a severely disturbed child. Because of the heavy demands made by the child, she was freed from her charge for a short period each day when others took over the

[page 19]

responsibility. At such times adult attention, which otherwise would have been directed towards the main group of children, was diverted towards the child with special educational needs.

4.7 Where special units were attached to schools individual children with special educational needs were usually withdrawn in order to receive help from specialist teachers and speech therapists; there were clear advantages where specialist teachers and nursery teachers worked closely in arranging a child's day and where there was a clear role for the specialist within the nursery itself. It was noted that where a group of children with hearing impairment was integrated with a nursery group already containing other children with special educational needs, it was these last children who were most deprived of adult time and support.

4.8 A contribution of crucial importance to the provision of good nursery education is the successful intervention of staff in the play activities of children so that their potential educational value can be developed to the full. It was in this aspect of their work where a majority of teachers were less proficient. While it was clearly apparent in most nurseries that activities were carefully supervised, much less frequently did members of staff play an active part and thus possible advantages to children's learning were overlooked. For example, participation in the domestic play area could provide a useful opportunity for promoting mathematical thinking and reasoning and provide a pattern of language skills which children might ultimately take as a model.

4.9 Opportunities for positive involvement in play were frequently missed when teachers were engaged in less significant activities. For example, where:

teachers remained aloof from play once equipment and materials were provided

more time was spent in arranging and clearing away than in participation in the activity

the teacher's role was limited to the increase of children's vocabulary rather than to the use of language as a whole (though the desire to improve language should not alone be the reason for participation in play)

there was too much emphasis on supervising table activities which prevented teachers from being involved in other forms of activity

teachers were concerned only with children's immediate demands.

[page 20]

4.10 By contrast, however, in a small proportion of nursery schools and units teachers were involved to great advantage in the children's activities. One such nursery arranged well planned activities which the adults shared with children who were drawn into groups throughout the session. There the opportunities for the development of language and other skills were many and always appeared to be exploited without any artificiality. In another nursery, the involvement of teachers and nursery nurses was sensitive and included noting the effect of their questioning, informing and probing. All members of staff were well aware of the appropriate moment to join in, to withdraw or to be passive observers.

4.11 The need for positive intervention of this kind was even more evident where teachers were dealing with children with special educational needs. Its value to such children is obvious, but in some instances required a more effective use of available adults or even a more generous staffing ratio.

4.12 Where extra time was spent with such children although often appropriate in amount, it was frequently used for no clearly defined purpose and with no change of teaching strategy. The need for any differentiation between children was thought unnecessary. The idea of personal programmes of activities for children with special needs was quite new to teachers. The only special programmes in some nurseries occurred where speech therapists had given advice but even then no further thought had been given to their extension.

4.13 However, when members of staff were well deployed and they understood the skills of involvement and intervention, as they did in a small number of schools, every child was able to receive appropriate time and teaching and, in one instance, the staff used their open-plan building to full advantage in achieving this.

4.14 Understandably, in special nursery classes, care, safety and physical comfort were important aspects of provision, and played a large part in the allocation of staff duties and responsibilities. Sometimes these tasks were the only ones allocated to non-teaching staff. There were indications that in some of the nursery classes in special schools undue emphasis on these parts of the daily programme was severely reducing the amount of time actually spent on education.

[page 21]

4.15 Since nursery classes in special schools were more generously staffed, poor deployment of adults was even more obvious than in ordinary nurseries. It was most manifest when teaching approaches were, sometimes inappropriately, general rather than concerned with individuals or small groups. For example, it was unnecessary for 5 or 6 adults to join some 13 more able physically handicapped children in a sing-song or for several adults to listen to a story with a small class of children. In 2 schools, teachers had developed new classroom management skills following attendance at courses on 'The education of the developmentally young', and these were increasing their efficiency in the most beneficial use of time spent with very heavily and multi-disabled children.

4.16 If the work of some nursery classes in special schools was imprecise in meeting individual needs, there were others where individualisation of programmes was well understood by teachers. In more than half the nurseries in special schools teachers, with different levels of competence and skill, were formulating teaching goals for individual children and working towards these.

4.17 While few ordinary nurseries made special provision, teachers in special schools were much less effective in meeting the more commonly shared needs of under-fives. These children, even when fully able to do so, were not always free to make choices or judgements, or free to experiment, investigate and explore. The need for periods of imaginative play was often ignored. One nursery which did not fail in this way had provided an excellent nursery environment with discrete areas given to different kinds of play. Handicapped children were able to play freely in one of these areas at different times with adults present but choices were made as wide as possible and of a kind which matched other more directed teaching received by the children. In another special school nursery a teacher deliberately introduced language experiences into the practical play situations of the children's choice and, in another, 'group leaders' were directed to work in a particular area for the purpose of sharing and extending their play. There were times for imaginative and role play with adults available to help those incapable of using dressing up clothes.

4.18 About half of the special school nursery classes were considered to be fully meeting the educational needs of their under-fives. There were others where some progress in development could be recorded, chiefly in physical and social aspects but sometimes in all areas of growth. However, children often showed only a limited ability to become involved in general play with confidence and to apply successfully what they had learned in more specific programmes.

[page 22]

4.19 Where nursery education was most effective all or many of the positive factors reviewed in this document were seen. In these nursery schools and units children were able to choose freely from activities and materials varying in difficulty and complexity. These had been carefully selected from a wide range of provision and planned to promote the learning and development of individual children within the total group at whichever age and stage they had reached. In such conditions children functioned with confidence and success. Sometimes family grouping allowed each adult to take responsibility for a small number of children thus increasing the very young child's sense of security and, providing for teachers and nursery nurses, a clear and less formidable task of the assessment and monitoring of children's development and of their participation in activities of the nursery. About one in three of the nursery schools and units met all or many of the criteria. Not all of them had children with special educational needs on roll. (One of these nurseries is more fully described in Appendix 4).

4.20 It was chiefly in these nurseries, about one in five of all ordinary nurseries, where children with special educational needs flourished. Where nursery education in fact was at its best and where support agencies were adequate and well used the needs of the great majority of children, including those with significant difficulties in learning or with the milder forms of emotional or behavioural disorders were being met. In such nurseries, children's progress was very satisfactory not only judged by means of observation or discussion with teachers but by reference to records and reports. This is not to say that some children with milder conditions were not making progress in nurseries with less systematic procedures for assessment, record-keeping and programme planning; a majority of such children were reported to have gained socially and, in a few cases, had also shown improvement in physical or cognitive development. But where the work of the nursery was without systems for assessing and recording development or lacked planning and teaching procedures, the influence of nursery education was difficult to distinguish from normal maturation or from raised levels of awareness occasioned by the stimulating social environment. In some schools the teachers were quite unaware that the needs of children were not being met and were content just to keep them occupied.

4.21 In one or two ordinary nurseries, work was sufficiently structured and planned to meet the needs of some children with more serious impairments but often teachers were without the expertise necessary for either diagnosis or educational treatment unless as in 2 or 3 instances nursery teachers had become

[page 23]

proficient because of their close association with special units attached to their nurseries.

4.22 The progress of the children in some nurseries was judged to be less than it might have been if tasks had been more precisely planned to meet individual needs. There were, for example, children, who long after admission to nursery education, continued to be isolated in their play, unable to make good relationships and who talked little or not at all to adults or other children. There were children who were functioning at a very low level and though progressing socially were at considerable disadvantage in trying to keep up with other children.

[page 24]

5. Conclusions

Nursery education

5.1 Nearly all ordinary nurseries were proficient in providing a range of materials, equipment and activities intended to foster the development of young children generally. For nursery education to be fully effective, however, these experiences have to be matched to the known needs of particular groups or individuals and planned on the basis of accurate assessment and recording. A further feature of effective nursery education is the well judged participation of teachers in guiding and extending the various activities of the children. Education in about one-third of nursery schools and units reached this high standard.

5.2 Where nursery education was at its best in ordinary nurseries and where support services were adequate and well used, the varying needs of the great majority of children between 3 and 5 years of age, even of some with quite significant special educational needs, were being effectively met. There is little doubt that any raising of standards of nursery education in general would directly influence the effectiveness of nursery schools and units in meeting the special educational needs of young children.

Children with special educational needs in ordinary nurseries

5.3 There were some children whose education required greater resources than even the best ordinary nurseries could provide. Among these were children with relatively mild but complex handicaps, who, though deriving some benefit from the nursery education provided, also needed educational objectives to be more clearly defined and more individual help. In such cases the active cooperation of other professionals was needed as well as a wider range of teaching skills than those usually available.

5.4 It may be considered necessary, in the future, for such children to be included in procedures similar to those for some 2 per cent of children who are more severely disabled. This might enable nurseries to draw more easily on the help and support needed in dealing with this group of children.

[page 25]

5.5 There were also in the ordinary nurseries visited some severely mentally handicapped or severely disturbed children who, in addition to the usual resources, required additional numbers of staff if the education of the rest of the children was not to be adversely affected. It was possible that in certain of such cases, education might have been more appropriately provided elsewhere. It would seem that there is a proportion of children for whom, at the under-fives stage, nursery classes in special schools are necessary.

5.6 Whenever children presenting serious difficulties in learning or management are placed in ordinary nurseries, consideration needs to be given to the appropriateness of the overall staffing ratio if all the children present are to benefit. On the whole, an increased establishment is likely to afford more flexibility in staff deployment than the appointment of extra staff to work with designated children.

Nursery teacher education

5.7 Though few teachers in ordinary nurseries had received training to prepare them for work with children with special needs, some had attended relevant in-service courses and many had had experience with individuals, some over long periods. Rarely was there any problem in identifying the children with difficulties; but teachers were often slow in seeking or failed to find suitable remedies for their difficulties. There was, not surprisingly, a widespread demand for in-service courses directed towards meeting the special educational needs of young children. It also became clear that there are areas of initial teacher training which may need to be given greater emphasis. Observation, assessment and recording procedures were often inadequate to plan and implement educational objectives. In many instances the absence of these was undoubtedly the cause of many of the diffuse methods of teaching observed and the failure to adapt approaches precisely to overcome or ameliorate perceived difficulties.

5.8 Special skills currently being developed by some working in special schools need to be shared with colleagues in nursery schools and units. Such skills include that of planning educational programmes for individual children based on a knowledge of early development and how it is affected by different handicaps and the skill of seeking and using the advice and help of other professionals in such planning. There is a need to be able to recognise when, for certain children, the usual modes of learning in the early years, such as creative and expressive

[page 26]

play, exploration and experiment, are not appropriate; where, instead, a change of approach to teacher initiated and directed activities is likely to be more effective. At the same time as employing such an approach with some children, nursery teachers need to ensure that a full range of opportunities for exploration and discovery are still readily available to the majority of the children. Nursery teachers may also need to be made aware of such techniques as task analysis, behavioural approaches and language and developmental programmes.

Nursery education in special schools

5.9 Nursery classes in special schools, with their necessarily greater resources, were providing for the more heavily handicapped minority. In the best of these, the importance of education did not suffer at the expense of high quality physical care, nor were the broader educational needs of under-fives lost sight of in efforts to overcome inevitable limitations. It was also apparent that few had yet fully developed individual programmes designed to meet the specific needs of children. There is some evidence that teachers in nursery classes in special schools are beginning to increase their knowledge of good nursery practice in ordinary nursery schools and units; this trend needs to be encouraged and perhaps accelerated by visits from nursery education advisers.

Advisory and support services

5.10 In view of the extensive range of children with special educational needs found in them, ordinary nurseries lacked the amount of help required from specialist services of all kinds - psychological, medical, para-medical and, not least, educational, in order to achieve a fuller understanding of the children in their care. Contacts between teachers and other professionals were usually few and often superficial and opportunities for direct consultation, even in difficult cases, were rare. Indeed, in some instances, the range of difficulties was much wider than is usually to be found in classes of children of statutory school age.

5.11 While teachers in special schools had readier access to other professionals much remained to be done in coordinating the work of all who were involved with the children. Even with professional advice at hand, it was often presented in such a way that teachers were not able to make use of it. Jointly planned aims were a rarity.

[page 27]

5.12 If ordinary nurseries are to continue to admit the kind of children currently accepted, education cannot be fully effective until supporting and advisory services are made more adequate than they are at present. Close relations and exchange of information between ordinary and special schools and between nursery and special education advisory services are of mutual benefit and such arrangements need to be more widely developed.

5.13 There are obvious difficulties in trying to assess special educational needs across different cultures particularly where the first language of the parents and the child is not English. Continued attention needs to be given to how help can best be provided for teachers who are often well aware of their lack of knowledge about the culture and lifestyles of different minority communities in Britain, their lack of skill in responding to languages other than English and in teaching English as a second language.

Parental involvement

5.14 In most, but not all nurseries, parents were welcome visitors and some provided help with activities. While recent years have seen a growth of closer involvement of parents with professional workers in promoting the early development of handicapped children, such arrangements were rarely to be found in nurseries included in this survey. Where possible, a closer degree of cooperation might be mutually beneficial. This might be more easily achieved by the ordinary nurseries which are usually sited nearer to children's homes than are special schools.

[page 28]

Part 2

6. The children

Numbers and characteristics of children with special educational needs in ordinary nursery schools and units

6.1 It is not easy to define the 'child with special educational needs' but generally teachers are able to identify children who, for one reason or another, cause them some concern. For the purposes of this survey, teachers were asked to list those children who, in their view, caused concern, demanded more of their time and attention, were receiving medical or para-medical treatment or, possibly, were judged to require it. Teachers were asked to include children for whom the language of instruction was different from the language of the child's home only where such children were experiencing additional and obvious difficulties, for example, in manipulative play or in relationships with children of the same culture.

6.2 Each visiting inspection team was able to meet all but the small number of listed children who were absent on the days of the visit. In the short time available for observation of children and after discussion with staff, teams judged whether children should be retained on lists in the light of DES Circular No 8/81. The Education Act 1981, Paragraph 4, states that a child has special educational needs if he has a learning difficulty which requires special educational provision to be made to meet those needs. 'Learning difficulty' is defined to include not only physical and mental disabilities, but any kind of learning difficulty experienced by a child that is significantly greater than that of the majority of children of the same age. Some difficulty was experienced in discriminating between social, medical and educational problems in such young children, a large number of whom were newly admitted. Even where children had been in the nursery for a period of time, systematic records were rarely available to support any judgements, but amendments were made to some lists. Results showed that the average proportion of children with special educational needs was somewhere between 15 and 16 per cent. (See Appendices 1 and 2).

6.3 Where there were discrepancies between those listed by schools and those agreed by the team of inspectors, these often derived from a misunderstanding

[page 29]

of the criteria to be applied but there were also instances where teachers were aware of home situations and allowed such knowledge to colour their observations and expectations. This led them to include on their lists such children as those from single parent families, unsettled homes, those with sick or handicapped parents or siblings, those from service families or living in high rise flats even when these children made no extra demands on either the time or attention of members of staff. It was noted, however, that there were dangers in disregarding any difficulties of very young children; medical conditions might affect later learning and children taking rather longer periods than normal to settle down might experience other social difficulties later. A number of such children were among those whose development the nursery staff would continue to scrutinise. Set against this was the important fact that wide differences in individual performance must be expected at this stage when variations in the rate of maturation are considerable and quite normal.

6.4 About half of the nursery units and a third of the nursery schools admitted children from ethnic minority groups and were likely to have children on roll either unable to speak any English or without effective command over English as their second language. Teachers in a number of these nurseries expressed concern at their difficulty in identifying children within this group who might be delayed in speech development. Similarly, it was difficult to recognise the significant influences on children's behaviour in such multi-language situations. Two or three nurseries were fortunate in having either teachers or nursery nurses available who were able to speak one or more Asian languages adequately and were able to assist in the assessment of children. In these nurseries, it was possible to estimate children's functioning in comparison with what would be considered normal for children of the same age and so there were fewer instances of children from the cultural and/or linguistic minorities being wrongly referred as children with special educational needs.

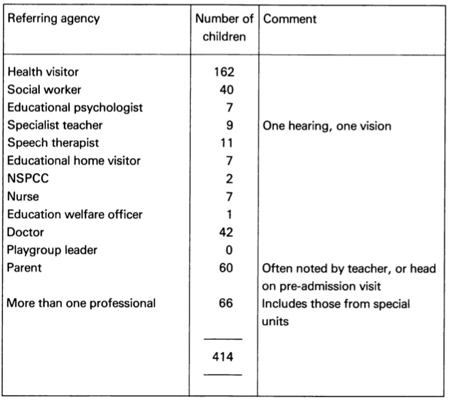

6.5 A majority of the children with special educational needs had been identified before admission, sometimes at 2 years but more often at 3 years, with health visitors playing the predominant role. (Table 1 - overleaf)

6.6 Of those whose special educational needs had been identified following admission to nurseries at 3 or 4 years by far the greatest proportion had attracted their teachers' attention because of their speech and language development. Other children with delayed or immature speech and language showed speedy progress only after extra long periods of settling. Emotional disturbance was

[page 30]

Table 1 Numbers of children identified by different referring agencies

often associated with, for example, social circumstances, with withdrawal, not speaking and an inability to mix with other children. Children were usually described as having behavioural difficulties when they were aggressive or destructive.

6.7 In the list below, the total does not match the number of children with special educational needs as some children are included in more than one category:

| general development | 57 | emotional development | 177 |

| language development | 177 | behavioural difficulties | 76 |

| physical development | 24 | | |

[page 31]

6.8 For the purposes of this survey there was no separation of the 2 per cent of children who, in the past, were designated as handicapped from the wider group of those with special educational needs; the difficulties presented by children varied greatly both in degree and complexity but none was heavily physically handicapped or required maximum physical care. Among those to be found in the nurseries were children such as these:

Sarah was admitted to the nursery following assessment by a doctor and speech therapist. Records indicated that she was born after induced labour, was lethargic as a baby, had failed a routine hearing test and was fitted with a hearing aid and that there were indications of nerve damage. Results of a Reynell Test administered by a speech therapist when the child was 2 years 9 months showed Sarah's verbal comprehension to be 2.04 years and expressive language 2.02 years. On entry to the nursery at 3 years, she was not toilet trained. Shortly after her admission, the school staff were informed by support services that her hearing aid was not required.

Six months later, though Sarah's gait was unsteady, she was beginning to climb large equipment. She repeated activities at which she had succeeded and was reluctant to attempt any new ones. She tended to sit and listen to or watch other children and would listen to a story or watch television. She was befriended originally by one girl but only for a very short time.

Her speech tended to be governed by a single pivot phrase 'I want'; this she had acquired since coming into the nursery.

Given pieces of paper and boxes at a "junk table", she managed to sweep the glue spreader across a box when it was held by an adult. She picked up a cardboard cylinder, put glue inside of it and then placed the non-glued exterior on to a cardboard box. She would sit looking at other children until an adult made an approach when she smiled, her eyes brightened and she appeared to be more aware of what was happening around her.

John was an aggressive boy but cried easily and tended to follow an adult around the playroom carrying a bag of personal belongings with him. His development was generally retarded and he lacked concentration but he was, at 4 years, beginning to listen to stories and instructions. His favourite play was on large physical equipment where he showed some ability.

[page 32]

Michael was a quiet undersized child who suffered from asthma and eczema. He rarely spoke and never played with other children though, in his second term in the nursery, he was working alongside others and tried to copy them.

Frank, nearly 4 years old, was a slight, very active boy, moved rapidly from one activity to another and did not join in with other children in the same play activity. Physically well coordinated, he was able to kick a ball, ride a tricycle, climb apparatus. He had an incontinence problem which had not yet been diagnosed.

Biddy, aged 4½ years, was a child with Down's syndrome, a heart problem and chest complaint and received speech therapy. The school had received results of a Reynell Test from a speech therapist at the local assessment unit showing that at 3 years 11 months her receptive and expressive language were at 2 years 8 months stage and 2-2½ years stage respectively. After a further 4 months in the nursery, her vocabulary had increased but she used very few sentences.

In her fourth term in the nursery, Biddy played with dolls and was usually to be found in the domestic play area. She could be seen, alone, dressing up, sitting in front of a mirror and whispering to herself or watching her feet wiggle as if in a world of her own. While in story time she would sit with other children, her eyes wandered and she would begin to touch other children and nearby objects.

Simon had been referred by support agencies following multi-disciplinary assessment. After some time in the nursery he still made no response to verbal encouragement or eye contact with adults or children. When brought into the playroom, he joined a nursery nurse and remained with her throughout the session, following her or standing close to her. Sometimes he demanded attention by leaning against her and intervening between her and other children or objects.

(For other examples, see Paragraphs 8.6 and 8.7)

[page 33]

Admission and transfer arrangements

6.9 Of the 10 local authorities visited only four had a general policy for admission of children to nursery schools or classes; the others left all admissions to the discretion of the heads though some education authorities made it known where they preferred a certain balance of full-time and part-time places, and of 3 and 4 year old children. Most children were expected to come within the 'normal range' but priority could be given to children with a developmental delay, mental or physical handicap or those considered to be disadvantaged in other ways. In one authority, a panel of 3 - the head, education welfare officer and nursery education adviser - together decided on those to be admitted from a waiting list, giving some priority to those identified by health visitors as those with special problems. A second authority had drawn up a list of adverse social conditions and priority admission was given to children for whom at least 3 factors applied. Another authority recommended each nursery to retain a certain number of places for children referred to them by other professional workers and such admissions were considered individually.

6.10 Though all nurseries gave some priority to the admission of children with special difficulties, in some cases certain provisos were made: for example:

the child should not require constant physical care or demand a one-to-one relationship;

the academic and social progress of other children should not be impeded;

an appropriate balance between children with special needs and others should be maintained;

there should be consultation with an agency referring a child;

no children using wheelchairs should be admitted where the nature of the nursery building would not easily permit it.

Where a nursery class already included pre-school children from a unit for the hearing impaired, other children with severe difficulties were not considered for admission.

[page 34]

7. Staff and their professional support

Staff in ordinary nurseries

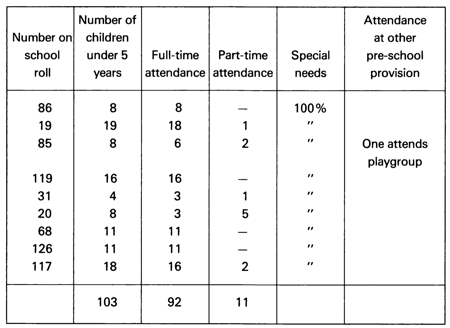

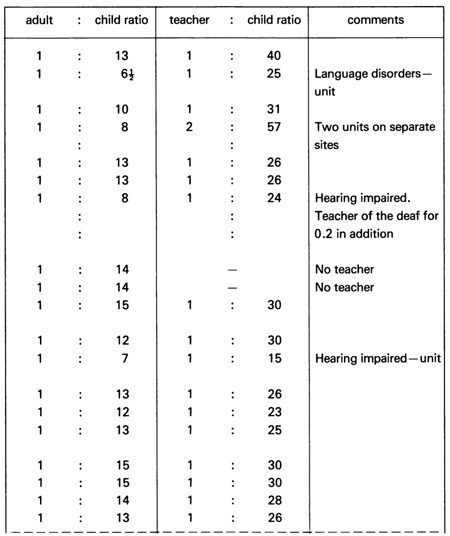

7.1 There were variations in the established pupil/adult ratios of classes in primary schools not only between those in different authorities but also between those within the same authority. Sometimes there was good reason for this; for example, one authority aimed for an adult/child ratio of 1 to 13 but were more generous when additional difficulties were present, such as when 2 nursery classes were on separate sites but attached to one school, or where there were special units. In another instance the staffing ratio in a nursery school appeared more favourable since an extra nursery nurse was appointed to have specific care of one child. (See Appendix 5). There were not always teachers present in nursery units. Two units in one authority were staffed by nursery nurses and 2 in another authority had a teacher for only part of the time. However, only 7 nursery units had a less favourable ratio than one adult to 13 children. (For details see Appendix 6).

7.2 Although statistics may seem to suggest that nursery schools were more favourably staffed than nursery units it should be remembered that these ratios included heads, many of whom were actively involved in teaching for the greater part of the week but also responsible for administration and for contact with parents and supporting agencies. In Appendix V the sizes of nursery schools are shown so that ratios can be set in perspective.

7.3 The heads of nursery schools as well as the majority of the teachers working in ordinary nurseries were trained for and often well experienced in work with young children. A few also held the certificate awarded by the Nursery Nurse Examination Board and some 5 or 6 teachers had taken courses leading to an Advanced Diploma in Early Childhood Education. Only 5 primary school heads had been trained to teach nursery aged children; the rest trained for infants and juniors with their teaching experience predominantly in those schools. Several showed interest in their nursery units but some admitted that they left them to the nursery teachers because of their own lack of knowledge.

7.4 Almost half of the nursery school heads and a number of the primary school heads as well as some teachers had either previously worked with groups of children with special educational needs or had opened special units in their

[page 35]

own schools. Many others could list handicapping conditions in individual children with whom they had worked.

7.5 There were ordinary nurseries where staff had formed strong effective teams for dealing both with normal and with less fortunate children. Such teams did not always include those who had, in the past, worked with special groups. Where a nursery was less effective, one or more of the following factors occurred:

the staff lacked cohesion and cooperation

the head or teacher delegated the major role to nursery nurses, accepting a supportive rather than a leading role

a probationary teacher was insufficiently supported with no model of good practice to follow

nursery staff were constantly changing as school staff were moved from classes of one age to those of another.

Staff in special schools

7.6 The staffing ratios in nursery classes in special schools were generous, a reflection of the serious management needs of the children, many of whom were heavily physically disabled. (See details in Appendix 7). Of 11 teachers employed in the special school nursery classes, only 2 were trained to teach pre-school aged children and only one had worked with normal under fives. This shortcoming was rarely offset by support from the heads for, on the whole, their expertise was likewise limited but 1 or 2 teachers were themselves involved in Advanced Training Courses on Early Childhood Education. On the other hand, all but one of the heads and more than half of the teachers were either already qualified or working towards advanced qualifications in the teaching of handicapped children, and in the case of the heads, had had many years in special education.

Professional support for teachers - in-service training

7.7 In the special schools it was customary for teaching staff, with nursery nurses and therapists, to attend courses which aimed to increase knowledge and

[page 36]

competence in the use of specific methods of working with seriously disabled children. Included in these courses were those arranged by the Department of Education and Science, local education authorities and universities and by voluntary associations. Subjects included:

Makaton, Paget-Gorman - signing systems for use with children with communication difficulties.

Specific handicapping conditions - medical, visual, hearing, etc.

Behaviour modification including a course concerned with the education of the developmentally young.

Curricular areas: music, swimming, language and speech.

7.8 In rather fewer than half of the ordinary nursery schools and units members of staff had attended no recent in-service courses. This was, however, in sharp contrast with others where members of staff had been on several. Whilst teachers in almost all nursery schools had received in-service training, some school-based, on aspects of the education of children with special educational needs, only about half of those in nursery units had attended such courses though some teachers had attended courses on related subjects. Special education topics included those on:

Children with minor handicaps

Special needs

Troubled children

Motor skill impairment and remediation

It was noticeable that some authorities had approached the arrangement of such courses for members of staff in ordinary nurseries with more urgency than others.

7.9 Special schools usually included subjects of topical interest in their school-based in-service training programme but there were topics which teachers felt they needed to consider further; these included 'Music and movement for the handicapped', 'Feeding problems' and 'Curriculum development'. Only one school mentioned general courses on educational provision and programmes for

[page 37]

the under-fives yet this, as indicated in earlier sections of this report, was perhaps one of the areas of greatest need.

7.10 Several teachers in ordinary nurseries expressed their need for more courses on children with special educational needs and some were precise in their requirements, for example, 'looking at child development with a view to breaking it down into structural learning situations that would help a child with learning difficulties'. Another teacher mentioned, 'How to discover and tap local resources for advice and help', and yet another, 'Strategies recommended by specialists'. But by far the most frequently expressed need was for advice and help in dealing with speech and language disorders with some 20 requests for practical information so that the work of the speech therapist could be continued or supplemented by nursery staff. Because of the difficulties teachers faced in identifying special needs in children for whom English was a second language, there were requests also for courses about assessment in a multi-cultural context. Thirteen references were made to the treatment of emotional disturbance or disruptive behaviour and a similar number to the identification and treatment of children with special educational needs especially those with multiple difficulties. The staff of 3 nurseries wanted to increase their knowledge of gifted children.

Advisory support for teachers

7.11 All special schools were visited by advisers for special education, some of whom were actively involved in the work of schools. Only 2 had been visited by an adviser for nursery education and one head was unaware that the authority provided such a service. A very small minority of ordinary nurseries had received visits from or had had contact with advisers concerned with special education; those which had were for the most part those with special units attached. A similar proportion of schools had made some links with local special schools.

7.12 There was one authority without an adviser specifically for nursery education and schools in that authority were among some 14 which reported that they received neither visits nor support. The range of help available in other nursery schools and units was wide, ranging from minimal to very active, with the adviser arranging or attending the monthly meetings of nursery staff and visiting all nurseries in the area on a regular basis. In one authority it was said that advisory visits had become less frequent because of financial limitations.

[page 38]

7.13 A head of a school for deaf children was particularly supportive of a unit for hearing impaired children in a school nearby. One special school had arranged some part-time teaching for a child with special needs in an ordinary nursery.

7.14 Some of the most valued support to nurseries, whether special or ordinary, was said to come from Child Assessment Units in their localities. Nurseries from 3 authorities referred to the high degree of cooperation and quality of information from these sources.

[page 39]

8. Relations with other services and with parents

Children in special school nursery classes being visited by supporting agencies

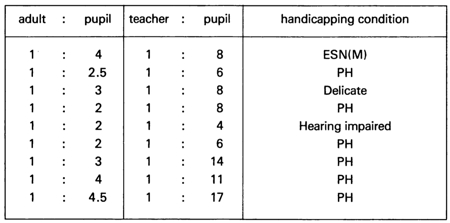

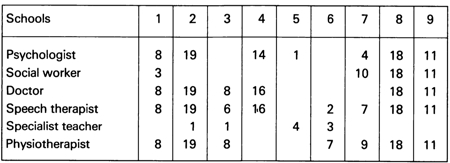

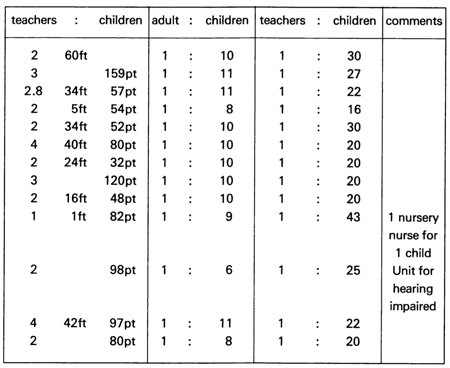

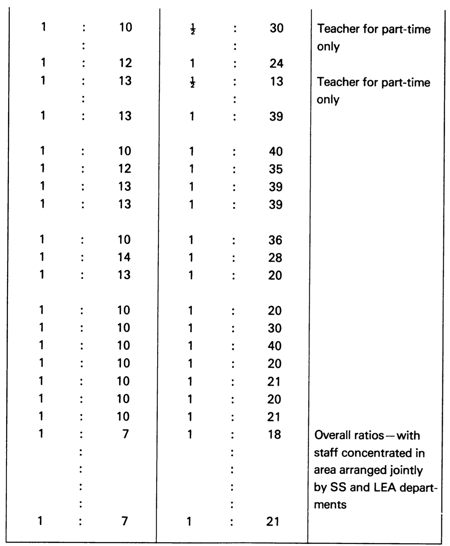

8.1 Almost all children in nurseries in special schools attended hospital or special clinics, sometimes held in their own schools, for both treatment and checks usually two or three times annually. Almost all these children were also visited regularly by a medical officer and the majority received school based physiotherapy and speech therapy. Educational psychologists had some involvement with special schools but visits were infrequent in some instances and nursery departments could secure only a small proportion of psychologists' time. The involvement of specialist teachers and social workers, except in three schools was minimal. (See Table 2).

Table 2 Children in special school nursery classes being visited by supporting agencies

8.2 The responses of some schools indicated that they were less than satisfied with the amount of support they received from other services. There were those where arrangements had only very recently applied or where a newly trained speech therapist was just settling in to her post. Sometimes the length of visits was strictly limited and affected the quality of advice given. There were instances where, for the most part, children were withdrawn from the classroom for

[page 40]

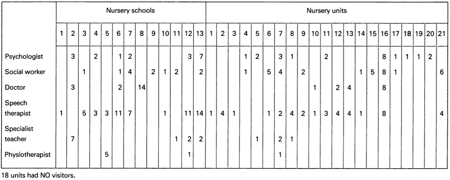

Table 3 Children in ordinary nursery schools and units being visited by supporting agencies

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 41]

speech therapy or physiotherapy and little or no feedback, except of a superficial and brief nature, reached the teachers. Visits of psychologists were, on the whole, considered less useful in so far as they frequently produced a general assessment of a child rather than advice on the nature of his learning and suggestions for teaching strategies which might be effective.

8.3 About one in five of the children with special educational needs in ordinary nurseries attended hospital for treatment or for checks; such visits were made chiefly at less than six monthly intervals. Only four children attended child guidance clinics. Some nurseries reported that they received no visits from support agencies (see Table 3) and it was stated that one authority had a policy that supporting services were not available to under fives although one head was urgently seeking help for children in his nursery class.

8.4 The finding that ordinary nurseries received less general support than special schools was not unexpected but in many instances it was insufficient or non-existent. On the whole nursery schools received more support than nursery units possibly because they admitted a greater number of more heavily disabled children but partly because of the energies and determination of some heads.