APPENDIX II

SPECIALIST TEACHERS

1. SPECIALISTS IN ART

(1) The Present Courses

1. Students who have taken an approved diploma followed by a course of professional training of two terms receive a qualification to teach art, or any branch of art to which the diploma is relative. The diplomas taken by intending teachers are, in order of frequency, drawing and painting, design, architecture; and the duration of the diploma course is four or five years.

(2) Recommendations

2. We agree with the general opinion of our witnesses that the diplomas which are at present accepted should continue to be accepted; and that these provide an adequate technical preparation for the teaching of art up to the highest classes in a senior secondary school. If a special teacher's course should be instituted, we are of opinion that it could profitably include a university course in Fine Art together with some study of the art departments of museums.

3. Under our proposed principle that the technical requirement should be the possession of an approved diploma or an equivalent qualification, it should be possible to admit to training artists, without a diploma, who have had successful experience in any suitable form of art work. Such candidates would normally have to take certain classes at an art college and a university, and the length of the course should be decided in conformity with the individual circumstances.

4. The course of professional training should be extended to the equivalent of one year of full-time study.

2. SPECIALISTS IN MUSIC

(1) The Present Courses

5. The technical requirement is the possession of the diploma (or degree) of a university or other recognised institution, and a list of the degrees and diplomas that are accepted is given in the Prospectus of General Information issued by the National Committee. They are of varying range and standard. Many can be taken without attendance at an institution of musical education, and some can be obtained at such an age that it is possible to qualify as a specialist teacher of music at the age of 18 years and 6 months. All applicants for admission to training must have adequate facility in singing, pianoforte playing and harmony.

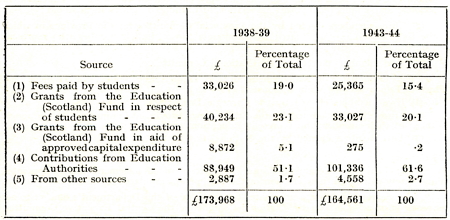

6. The course of professional training is taken after obtaining the degree or diploma, and extends to two terms for a qualification in one branch, of music or to three terms for a qualification in two branches. The branches in which the qualification is most commonly granted are class-singing and pianoforte.

(2) The Arrangements for Instruction in Music in Schools

7. Some specialists in music teach only singing; others are employed wholly in giving instruction in instrumental music to individual pupils or to small groups of pupils; others deal with both vocal and instrumental music. The music specialist often supervises the musical work of the primary department, and he is expected to play a leading part in the general musical life of the school, being responsible for the organisation of school choirs and orchestras.

8. While this variety of function necessitates a measure of specialisation in the qualifications of music teachers, we recommend that candidates should have a general musical training and that the specialisation should be only on the instrumental side.

[page 76]

If a school staff did not have a teacher competent to teach a particular instrument the instruction of the pupils concerned could be provided by the part-time employment of private teachers or visiting teachers.

(3) The Normal Courses Recommended

9. It follows from the above recommendation that a course specially designed to meet the needs of teachers is particularly desirable in the case of music. It should be taken by full-time attendance at an approved institution of higher musical education, and the technical part of the preparation should extend to the equivalent of three years of full-time study. The professional training, extending to the equivalent of one year of full-time study, should be taken concurrently; so that the total length of the course of preparation would be four years. We are informed that a course of this type will shortly be available at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music, and we recommend that this should be the normal course taken by candidates for the qualification in music.

10. We recommend that a post-graduate or post-diploma course should also be available. Its normal duration should be one year, and it should be open to graduates in music of Scottish or other approved universities and to holders of certain carefully selected diplomas, some of which may have been obtained without three years' attendance at an institution of higher musical education. Only such degrees and diplomas should be accepted as have a direct relation to school music requirements, and if necessary the course of training should be extended to allow the candidate to supplement his attainments on the technical side.

(4) Special Course for Teachers already qualified to Teach General Subjects in Primary Schools

11. Under the present system, a student who has completed a course of training for the Teacher's General Certificate* and has one of the accepted diplomas in music may obtain the Chapter VI* qualification in music by taking an additional course of one term. All our witnesses were agreed as to the value of this type of teacher, and we recommend that the avenue be left open, subject to the following conditions: (1) that the student has taken the special course in music during the training as a teacher of general subjects in primary schools, (2) that the diplomas to be accepted for this purpose, which need not be of so high a standard as those required for admission to the one-year post-diploma course, be carefully selected by the training authorities, and (3) that the additional course of professional training be extended to one year.

(5) General

12. All candidates for admission to training for the specialist teacher's certificate in music should be required to satisfy the training authorities as to their proficiency in singing, pianoforte playing and harmony, and training institutions should be so staffed that lecturers in music have adequate opportunities to supervise the teaching practice of their specialist students.

3. SPECIALISTS IN AGRICULTURE AND RELATED SUBJECTS

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

13. Up to now the demand for specialist teachers of agriculture has been small, but it is likely to increase considerably.

14. Agricultural courses in schools are sometimes conducted by teachers, without the Teacher's Technical Certificate, who have a Chapter V* qualification in a suitable science subject, such as botany, together with qualifications undler Article 39* in related sciences. Provision is made in the Regulations for a Chapter V qualification in agriculture, the technical requirement for which is an honours degree of the first or second class in agriculture, but the number of students who have taken this qualification is negligible.

15. For the Chapter VI* qualification the technical requirement is the possession of the diploma of a recognised college of agriculture or the degree in agriculture of a Scottish or other approved university, and the qualification granted is in agriculture, or horticulture, or any branch of rural economy to which the diploma or degree is relative. The duration of the course for an ordinary degree of B.Sc. in agriculture of a Scottish university is three years, and the diploma courses in the agricultural colleges extend to two or three years. The course of professional training, which is two terms in length, is always taken after obtaining the degree or diploma.

16. The agricultural colleges offer two-year diploma courses in dairying and poultry-keeping; and a course of three years leading to qualification in both subjects. A few students have taken the Chapter VI* certificate in these subjects, but such instruction as is given in them in day schools is provided mainly by local instructors of the colleges of agriculture.

*See footnote to paragraph 6 of the Report.

[page 77]

(2) Recommendations

17. Our recommendations are based on the view that the teaching of agriculture and related subjects in a narrow technical sense should not find a place in day schools. Agricultural courses should deal largely with the basic sciences, but with a definite bias towards agriculture which would be intensified in the higher forms.

18. Such courses could safely be entrusted to teachers with the specialist teacher's certificate in a suitable science subject and a qualification for the teaching of related sciences to the younger secondary classes, provided that they have a sufficient agricultural background. The latter could be taken for granted if the student has been brought up on a farm: other students could obtain it by periods of work on a farm during vacations.

19. We recommend that an honours or ordinary degree in agriculture of a Scottish or other approved university be accepted as satisfying the technical requirement for the specialist teacher's certificate in agriculture: but if the degree course does not include a period of practical work on a farm this should be taken in addition to the normal university and training courses. The professional training should extend to the equivalent of one year of full-time study.

20. We agree with the opinion of the great majority of our witnesses that the present diploma courses available at the agricultural colleges do not adequately prepare a teacher to teach agriculture up to the highest class in a senior secondary course; they are adapted mainly to the needs of young farmers and are too narrowly vocational in aim. We therefore recommend that they should not be accepted as satisfying the technical requirement for the specialist teacher's certificate, but that the agricultural colleges, in conference with the training authorities and the veterinary colleges, should consider the possibility of the establishment, at one or more centres, of a diploma course specially designed for teachers. The course should be of the concurrent type, and the total duration, including technical preparation, farm experience and professional training, should be not less than four years. It should be of a comprehensive character, including some instruction in all the main related branches, horticulture, forestry, dairying, poultry-keeping and bee-keeping. If highly specialised instruction in any of these related subjects should be necessary it could be provided by the employment of part-time specialists, and provision should be made for teachers to extend their knowledge of these subjects through courses for the further instruction of teachers in service. An alternative suggestion that the diploma course should provide for a measure of specialisation as in domestic subjects did not find favour with our witnesses.

21. All courses leading to the specialist teacher's certificate in agriculture should include some instruction in rural economy as described in paragraph 87 of the Report.

4. SPECIALISTS IN COMMERCIAL SUBJECTS

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

22. The technical requirement for the Teacher's Technical Certificate in commercial subjects is the possession of the diploma of a recognised commercial college or the degree in commerce of a Scottish or other approved university.

23. Degrees in Commerce (B.Com.) are awarded by the University of Edinburgh, and although powers to award degrees exist at Aberdeen and St. Andrews they are not in active operation. Degree courses do not include shorthand and typewriting, and no provision is made for practical office experience. In view of this, the Regulations for the Training of Teachers, as amended, require that a course of professional training shall not normally be begun, unless the candidate has satisfied the training authority of his proficiency in shorthand, typewriting and book-keeping.

24. The only centre with a recognised diploma course is the Glasgow and West of Scotland Commercial College. Intending teachers are advised to take a special diploma course extending over three years, in which shorthand, typewriting, book-keeping and practical office experience are included. A student who has not a pass on the higher grade in commercial subjects or economics in his Senior Leaving Certificate may require four years.

25. The course of professional training, which is of two terms, is almost always taken after obtaining the degree or diploma.

(2) Recommendations

26. We recommend that the technical preparation for the specialist teacher's certificate in commercial subjects should be taken by attendance at a course at a recognised commercial college or at a university. The former course, which should be specially designed to meet the needs of teachers, should be based on the course at present offered at the Glasgow and West of Scotland Commercial College; and it should include shorthand, typewriting, book-keeping and a period of not less than one year of approved business

[page 78]

experience. Consideration should be given to the possibility of broadening the present course on the cultural and economic sides and of arranging that certain classes should be taken at a university. The content and character of the course should be determined by the authorities of the commercial college in consultation with the training authorities. While we realise that there are special difficulties in the case of commercial subjects in that three institutions would be concerned and that a period of office experience would have to be included, we are of opinion that the professional training find technical preparation should be taken concurrently.

27. The degree in commerce of a Scottish or other approved university should also be approved as satisfying the technical requirements. Before entering upon their year of professional training, graduates in commerce should be required to have had a period of not less than one year of approved business experience and to satisfy the training authorities that they have reached a sufficient standard in shorthand, typewriting, book-keeping and commercial practice. We understand that the National Committee (Scotland) for Commercial Certificates propose to institute a special examination for teachers of commercial subjects which would be suitable for this purpose.

5. SPECIALISTS IN DOMESTIC SUBJECTS

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

28. The main subjects included in the three diplomas of a college of domestic science which satisfy the technical requirements are as follows:

Diploma I. Cookery, laundrywork, housewifery and needlework.

Diploma II. Needlework, dressmaking, millinery and home crafts.

Diploma Ill. Cookery, laundrywork, housewifery, needlework, dressmaking.

These diplomas are taken almost wholly by intending teachers and the total duration of the course of technical and professional preparation is three years for Diploma I or Diploma II, and four years for Diploma III. In the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science all courses are of the concurrent type: in other colleges only certain courses are concurrent or partly concurrent.

(2) Recommendations

29. We recommend that the present three types of diploma should continue to be accepted, but we suggest that the domestic science college authorities should reconsider the combinations of subjects for the diplomas in the light of the changing needs of the schools. Diplomas I and II require different aptitudes, which are not always combined in the same student, and the present arrangement is suited to the staffing requirements of Scottish schools. In certain of the smaller secondary schools the amount of work in domestic science may not be sufficient to warrant the appointment of two specialists, but the needs of such schools could be met by the employment of visiting teachers or of teachers with Diploma III.

30. The present courses for the diplomas fall short of modern requirements in two ways. In the first place the professional training should be extended to the full equivalent of one year of full-time study for all students: in the second place all courses should, as we have recommended in paragraph 119 of the Report, provide for the continuance of the student's general education and for the cultivation of some cultural interests that have no direct professional bearing. We therefore recommend that the total length of the course be four years for students taking Diploma I or Diploma II and five years for those taking Diploma III.

5. SPECIALISTS IN PHYSICAL EDUCATION

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

31. The preparation for Chapter VI* qualification in physical education is taken at the Scottish School of Physical Education and Hygiene (for Men), Jordanhill, Glasgow, or at the Dunfermline College of Hygiene and Physical Education (for Women). These institutions are under the management of the National Committee. The course, which is of three years' duration and of the concurrent type, leads to a diploma in physical education and to the Teacher's Technical Certificate in physical education. Both institutions also offer a one-year course leading to the same qualifications which is open to men and women who hold the Teacher's General or Special Certificate.*

(2) A Special Problem in the Training of Specialist Teachers of Physical Education

32. Many women specialists in physical education, and a smaller proportion of the men, find that on reaching the age of about 50 years their efficiency has begun to decline and that if they were to carry on with this strenuous work it would be to the detriment of

*See footnote to paragraph 6 of the Report.

[page 79]

their own health and professional satisfaction and to the educational disadvantage of their pupils. Resignation would, however, entail serious financial hardship through loss of salary and reduction or even loss of pension. While it is true that a large number of women teachers of physical education leave the profession on account of marriage and other reasons before reaching the age of 50, the problem is serious.

33. We are informed that it would be extremely difficult to change the Superannuation Scheme in such a way as to allow teachers of physical education to retire with a pension at all earlier age than 60. With the present scale of contributions it has been actuarially estimated that retirement even at 55 would allow only about 72 per cent of the pension payable on the full scale, and this reduction would be additional to that which follows from the fact that the teacher would have five years less pensionable service. To secure payment of an acceptable pension at 55 it would therefore be necessary to increase substantially the scale of contributions. Further difficulties would arise in connection with disablement pensions and with the reciprocity between the Scottish and English Schemes.

34. We are of opinion that the difficulty can be best met by so planning the course of training that the teacher will be able, at the age of about 50, to transfer to some form of service, preferably recognised for the purposes of the Superannuation Scheme, that will not involve so heavy a physical strain. Some teachers will no doubt find posts as supervisors, inspectresses, or organisers in connection with clubs, recreative physical education or training schemes for youth; though authorities may hesitate to appoint to the latter types of post teachers who have lost some of the energy and enthusiasm of youth. Others, perhaps after a short period of further training, may be employed in physiotherapy, remedial work, rehabilitation, occupational therapy, massage and medical gymnastics. With the modification in the course of training which we recommend some will, we hope, be able to transfer to the teaching of other school subjects. When a further period of training is necessary we recommend that the teacher be granted full salary during attendance at the training course.

(3) The Normal Course Recommended

35. We recommend that the normal course of preparation should be a combined course of technical and professional training taken at the Scottish School of Physical Education and Hygiene (for Men) or the Dunfermline College of Hygiene and Physical Education (for Women) (see paragraph 41 below). The course should be extended to four years to provide for - (1) a broadening of the student's general culture, (2) a fuller training in methods appropriate to primary schools and junior colleges, (3) the obtaining of a partial qualification to teach some other subject than physical education. The plans for providing a partial qualification for some other branch of teaching will have to be worked out, but we give a few examples to illustrate the kind of arrangement we have in mind. (1) A student with a diploma in music could take some methods and practice in that subject. (2) In view of the broadening of the course which we have recommended, it should be possible to give a partial qualification for the teaching of general subjects in primary schools. The student would have had a course in English. Attendance at one or more suitably chosen classes at the university could be arranged, together with a short course of primary training for a limited age range and a limited group of subjects. (3) Courses could be planned which would lead to a qualification to teach a limited number of subjects to younger secondary classes. If a university class in a science subject were taken in addition to the courses in anatomy, physiology and hygiene already included in the course, the student would be qualified to assist with some of the science teaching in secondary schools, or with the work of the hygiene, mothercraft and pre-nursing classes. (4) To meet the needs of students who are not interested in ordinary primary or secondary teaching, other directions of specialisation could be arranged to give a partial qualification for one of the lines of work mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

36. We are of opinion that it would not be practicable to allow any student, within the four-year course, to take the full qualification for the teaching of general subjects in primary schools: nor can we recommend that a course leading to this double qualification should be made the normal one. Such an arrangement would not commend itself to the majority of the students, many of whom have little taste for academic studies and will never teach any subject other than physical education. It would therefore have an adverse effect on supply. On the other hand, we feel that it would be an advantage if a five-year course were available for such students as desire to take the double qualification.

37. In the case of specialists in physical education with these partial qualifications there should not be too strict an insistence upon the normal requirements for the teaching of subjects; and they should be allowed to do a certain amount of teaching of the additional subjects all through their careers. Provision should also be made for allowing them to supplement their partial qualifications by attendance at courses for the further instruction of teachers in service or at courses of full-time training.

38. Along these lines it should be possible for a large proportion of the physical education specialists whose energies are declining about the age of 50 to find suitable

[page 80]

niches in the education service during the remaining years of their professional lives. To meet the needs of the growing number of existing teachers in this category we recommend that facilities be provided, through Article 55* classes or by granting leave of absence on full salary to attend full-time courses, by which they will be able to obtain partial qualifications of the types indicated above.

(4) Course for Teachers already Qualified to Teach General Subjects in Primary Schools

39. We were informed that many of those who have taken the present one-year course open to certificated teachers have done extremely good work and risen to posts of responsibility: and this is an avenue into the ranks of specialist teachers of physical education that we should be reluctant to close. On the other hand it is clearly impossible, even when allowance is made for the parts of the training which are common to the two courses, that the technical preparation in the one-year course could be as full as that given in the normal four-year course. This difficulty can be partly met by our previous recommendations that a fuller course of training in this important subject be given in all courses for teachers of general subjects in primary schools and that physical education should be one of the directions of specialisation open to students who take these courses. We therefore recommend that men or women who have specialised in physical education in their course of training as teachers of general subjects in primary schools should be able to obtain the qualification as specialist teacher of physical education by taking an additional course of one year.

(5) Extension of the Provision for the Training of Specialists in Physical Education

40. The statistics given in our previous Report show that the present facilities will not be adequate to meet the future needs of the schools and junior colleges, and we recommend that the training authorities should give early consideration to an extension of the provision both for men and for women.

(6) Location of the Women's College of Physical Education

41. The normal course which we have recommended could be provided only if the college of physical education is close to a training institution, university and other institutions of higher education. Dunfermline is an unsuitable centre from this point of view, and it is open to other serious objections. Facilities for teaching practice, already barely sufficient, will be quite inadequate in the future when the number of students is increased; students are isolated from those preparing for other callings; and inconvenience and loss of time are caused by the necessity of travelling to Edinburgh for certain parts of the training. While we realise that a change would involve serious administrative difficulties, we recommend that the women's college of physical education should be transferred to one of the towns in which the training institutions are situated.

7. SPECIALISTS IN ENGINEERING AND OTHER BRANCHES OF TECHNICAL INDUSTRY

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

42. Under the present Regulations the Teacher's Technical Certificate† may be granted in a branch of applied science or technical industry, the technical requirement being the diploma of a central technical college or institute or the degree in applied science of a Scottish or other approved university. Provision is also made for a Chapter V† qualification in engineering which is open to students who have a university degree with first or second class honours in the subject.

43. The duration of the course of training for the Technical Certificate is two terms, and there is a somewhat anomalous arrangement under which the Technical Certificate and the General Certificate may be obtained in a course of one year and one term, the same length as that for the General Certificate only. The course of training for the Teacher's Special Certificate in engineering is one year.

(2) Recommendations

44. While the demand for teachers with this qualification has hitherto been very small, it may well increase with the development of junior colleges and of technical courses in secondary schools. We therefore recommend that provision be made for a specialist teacher's certificate in engineering or other branch of technical industry and that the technical requirement should be the possession of a suitable diploma of a central technical, college or institute or a suitable ordinary or honours degree in engineering or applied science of a Scottish or other approved university.

45. In addition to the course of professional training, which should extend to one year a period of trade experience should be required. Many of the teachers with this qualification could be employed to teach technical drawing and mechanics even though they have not the full qualification in technical subjects with which we deal in the next section.

*See second footnote to paragraph 96 of the Report.

†See footnote to paragraph 6 of the Report.

[page 81]

8. SPECIALISTS IN TECHNICAL SUBJECTS

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

46. The present Regulations provide for a Chapter Vl* qualification in educational handwork or a craft the basis of which is the diploma in educational handwork of a Provincial Committee for the Training of Teachers, or any other approved diploma or certificate, or sufficient attendance at a recognised course of instruction and satisfactory proof of craftsmanship. In practice, the course is always taken wholly in a training college, and it leads both to a diploma in educational handwork and to the Teacher's Technical Certificate. More than two-thirds of the entrants are youths who have completed an approved apprenticeship; and, generally speaking, such candidates are admitted if they have reached a standard of general education equivalent to that of the Junior Leaving Certificate. The remainder are pupils who have completed a course of study approved for the purpose of the Senior Leaving Certificate but have had no apprenticeship or other trade experience. Failure to obtain the Senior Leaving Certificate does not necessarily involve the rejection of such candidates. The normal duration of the course, which is of the concurrent type, is two years, but it is often extended to three if the candidate has not completed an approved apprenticeship. The main technical subjects included are handwork in wood and metal, technical drawing and mechanics. A small number of students take an additional course of one year leading to the Article 39* qualification in art.

(3) Nomenclature

47. The three subjects, educational handwork, technical drawing and mechanics form a related group which experience has shown to be well suited to the staffing requirements of Scottish schools. We recommend that the group should form one of the subjects in which the specialist teacher's certificate is granted, and that the name applied to it should be "Technical Subjects".

(3) The Need for Specialisation within the Group

48. Having in mind the different aptitudes demanded by the three subjects in this group, the advanced instruction for which the teacher will have to be prepared, and the necessity for including a period of trade experience in many of the courses, we are of opinion that it would not be feasible, in a course of reasonable length, to train candidates up to the full specialist standard in all of the subjects. We therefore recommend that there should be two types of specialist teacher's certificate in technical subjects. The first would qualify the teacher to teach educational handwork up to the highest class in a senior secondary school and technical drawing and mechanics to the younger classes: the second would qualify the teacher to teach technical drawing and mechanics up to the highest class in a senior secondary school and educational handwork to the younger classes. The courses for both types should include training for the teaching of educational handwork in primary schools.

49. We realise that in smaller secondary schools it would often not be possible to have specialists of both types. In such schools the teacher appointed should be one who has specialised in handwork; and assistance with the more advanced work in mechanics and technical drawing would normally be available from teachers on the staff of the science and mathematics departments.

(4) Entrance requirements

50. We recommend that the following categories of students be admitted to training for the specialist teacher's certificate in technical subjects:

(i) Students, without trade experience, who have a Senior Leaving Certificate or the equivalent. While any Leaving Certificate group should be accepted, it is desirable that the certificate should show passes on the higher grade in one or more of the following subjects: (1) technical subjects, (2) mathematics, (3) science; and training authorities should have power to extend the course of training if the Leaving Certificate group is not entirely suitable.

(ii) Students who have completed an approved apprenticeship, provided that they have reached a standard of general education equivalent to that of the present Junior Leaving Certificate. A special entrance examination should be available for such candidates, and the standard of general education required should be revised from time to time in the light of the development of educational facilities and the number of candidates coming forward.

(iii) Students with a National Certificate (Higher), a suitable university degree, or a suitable diploma of a central institution, provided that they have had experience in an approved trade amounting to not less than two years and that they have reached a standard in English equivalent to that of the present Junior Leaving Certificate.

*See footnote to paragraph 6 of the Report.

[page 82]

(5) Courses

(a) Students with Senior Leaving Certificate but without Trade Experience

51. The course of preparation should extend to four years, of which roughly three years should be devoted to technical preparation, including one year of trade experience in approved workshops, and one year to professional training. During the year of trade experience the student should be required to attend evening continuation classes or day trade classes. It should be open to students taking this course to specialise either in educational handwork or in technical drawing and mechanics.

(b) Students who have Completed an Approved Apprenticeship

52. Such students will fall into different categories. For those who have had merely a day school education up to the compulsory age, together with subsequent attendance at day continuation classes, the course should be three years. If, in addition, the student has a National Certificate (Ordinary) or a City and Guilds Final Grade Certificate the course should be two years. It is desirable that most, if not all, of the students in this category should specialise in educational handwork,

(c) Students with National Certificate (Higher), a suitable University Degree, or a suitable Diploma of a Central Institution

53. The course of training should be one year, and should be devoted to professional training, with such supplementation on the craft side as may be found necessary. It should lead to specialisation either in educational handwork or in technical drawing and mechanics.

(6) Co-operation with Technical Colleges

54. While the courses should be planned by the training institutions, those which involve technical preparation should be run in close association with the technical colleges, partly to avoid duplication of courses and equipment and partly to give the students the advantages of participation in the life of these colleges. We recommend that co-operation between the training institutions and the technical colleges in this matter should be the subject of conference between the training authorities and the authorities of the technical colleges.

(7) Conditions of Service

55. It is desirable to attract into this branch of the teaching profession men who have had a considerable amount of industrial experience and who will therefore enter the profession at a relatively late age. Steps should be taken to safeguard the interests of such teachers by suitable placing on salary scales.

(8) Centralisation of the Training of Specialist Teachers of Technical Subjects

56. We have given careful consideration to suggestions that the training of specialists in technical subjects should be centralised either in one of the training centres or in a separate college of handicraft. It was pointed out that the number of students taking this training at some of the centres is relatively small and that, if the training were centralised, it would be possible to have a more adequate standard of staffing and equipment.

57. Centralisation would clearly be impracticable in the early post-war period; for the resources of the existing handwork departments will then be strained to the utmost. Thereafter, we estimate that the total number of students in the handwork departments will be in the neighbourhood of 220, a number which, in our view, would be sufficiently large to justify the retention of fully equipped and staffed departments in each of the four centres. It has also to be borne in mind that the requirements in regard to staff and equipment will be affected if effect is given to our recommendation that full use should be made of the resources of the technical colleges.

58. There are serious objections of a general educational nature to the policy of centralisation. Segregation of teachers of a special type during training should be avoided. The free association of craftsmen, primary teachers and specialists in academic subjects is to the advantage of all. Students of such subjects as handwork, art and music are invaluable in the corporate educational life of a training institution and in college projects; if they were centralised in one college, the life of the others would be seriously impoverished.

59. A policy of centralisation also leads to administrative difficulties. Students feel it to be a hardship that they have to go to a distant city for a training that could be provided in their own. The tendency is to centralise in the larger centres, partly because they are geographically more convenient and partly because they have more adequate facilities for teaching practice for large numbers of students. As a result, the large centres tend to become too large, while the smaller ones are depleted.

60. For these reasons we are unable to recommend that the training of specialist teachers of technical subjects should be centralised.

[page 83]

APPENDIX III

TEACHERS OF HANDICAPPED CHILDREN

1. TEACHERS OF THE BLIND

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

1. Two types of course are offered. The first is provided under Article 32(a) of, the Regulations and is open to blind or partially blind persons. The course, which is provided in connection with a school or institution for blind children, extends to three years in the case of non-graduating women and to one year and one term in the case of graduates. It leads to it qualification as "Certificated Teacher of the Blind", but students who take the course are not entitled to rank as "Certificated Teachers" for ordinary schools. The second type of course, which is provided under Article 51 of the Regulations, is open to teachers who hold the Teacher's General Certificate, and extends to one year. It leads to an endorsement of qualification to act as teachers of blind children. In the meantime all training of teachers of the blind is centralised in Edinburgh.

(2) Supply of Teachers of the Blind

2. As the number of children in Scotland, between the ages of 3 and 18, who require education by blind methods is under two hundred, the total number of teachers required at any one time is unlikely to exceed twenty. There are, however, many children so handicapped visually that education in ordinary schools would be detrimental to their sight or educational development. The number of such children is estimated to be 800-1,000, and if, as seems desirable, they were educated in central residential schools, the total number of teachers of the blind required at any one time would be about eighty.

3. While certain parts of the instruction of blind children may well be undertaken by blind teachers, such teachers are subject to physical limitations which no zeal or skill on their part can fully compensate, and we recommend that there should be a considerable increase in the proportion of seeing teachers of the blind. Great care should also be used in the selection of blind or partially blind candidates for entrance upon training. In no circumstances should the proportion of blind teachers to seeing teachers in a school for blind children exceed 50 per cent.

(3) Recommendations in regard to Courses of Training

4. We recommend that seeing teachers of the blind should take one of the ordinary teacher's diplomas followed by a period of service with normal children. Such teachers should be regarded as qualified to enter upon service in a school for the blind; but during their first two years they should be required to attend two vacation courses, of about three weeks each, in which they would receive instruction in methods of teaching the blind, history of blind education, physical and psychological problems of blind children; handwork, physical training, leisure activities, etc. We were assured by our expert witnesses that the training could be adequately covered in this way and that the arrangement would be more suitable than one under which the teacher had to return for a full-time course of training. On the satisfactory completion of the two vacation courses, the teacher would receive an endorsement of recognition as "Certificated Teacher of the Blind". A similar arrangement could be made in the case of teachers of visually handicapped children.

5. For blind teachers, we recommend that there should be a special course of training of the same length and as far as possible of the same character as that taken by teachers of normal children. It should be arranged in association with an institution for the blind and should lead to the qualification of "Blind Certificated Teacher of the Blind".

6. The training of blind adults is largely in the hands of technical instructors, frequently the foremen of workshops for the blind, and we recommend that they should have some special training for this work. It should be provided in a short course taken in the evenings or in vacations, and the instructors should be required to possess the Craft Instructor's Diploma of the College of Teachers of the Blind.

7. We recommend that the training of teachers of the blind should for the present continue to be centralised in Edinburgh.

2. TEACHERS OF THE DEAF

(1) The Present Training Arrangements

8. Under the present Regulations students may train for the qualification of "Certificated Teacher of the Deaf" without experience of the teaching of normal children. A woman student may take a non-graduate course of three years for the Teacher's General Certificate, and thereafter proceed to the special one-year course offered by the Department of Education of the Deaf of the University of Manchester. A graduate may obtain the Teacher's General Certificate and recognition as "Certificated Teacher of the Deaf" by taking a course of one year and one term, of which one year is spent at the Manchester course and one term in a Scottish training College.

[page 84]

9. Certificated teachers and other teachers who have displayed special aptitude as teachers of the deaf may also obtain recognition as "Certificated Teachers of the Deaf" by taking the one-year course at Manchester. Leave of absence for the year, usually with full or half salary, is granted by the teacher's employing authority. Maintenance allowances are granted by the National Committee for the Training of Teachers in exceptional circumstances.

10. The tuition fee for the Manchester course is met by the National Committee in all the above cases, and the granting of the recognition as "Certificated Teacher of the Deaf" is subject to the successful completion of a two-year period of probationary service in a recognised school for the deaf.

11. Provision is also made whereby persons who have had no reasonable opportunity of qualifying in the above ways, but have served with success in schools or institutions for the deaf approved for the purpose, and are fully competent to have sole and responsible charge of the education of deaf children, may be recognised as "Certificated Teachers of the Deaf".

(2) Supply of Teachers of the Deaf

12. From the point of view of hearing, children are divided into the following grades:

Grade I. Children with normal hearing, together with those whose hearing defect is so slight as not to interfere with their education in ordinary schools;

Grade II (a). Children who can make satisfactory progress in ordinary schools, provided they are given some help, by way of favourable position in class, by the use of individual hearing aids, or by tuition in lip-reading;

Grade II (b). Children who fail to make satisfactory progress in ordinary schools though given all the help advocated for Grade II (a) children; and

Grade III. Children whose hearing is so defective and whose speech and language are so little developed that they require education by methods used for deaf children who are without naturally acquired speech or language.

13. The existing provision relates almost wholly to Grade III children, the number of whom is estimated to be about 700, and the annual demand for teachers is about four. If the Grade II (b) children, estimated to number between 2,000 and 4,000, were provided for in separate schools and taught by qualified teachers of the deaf, an additional eight to sixteen teachers would be required annually. To meet the needs of children in Grade II (a) a reasonable number of teachers qualified in lip-reading should be provided.

(3) Recommendations in regard to Courses of Training

14. For the reasons given in paragraph 131 of the Report, we are unable to recommend the continuance of the arrangement under which training for the teaching of the deaf may be taken as part of, or immediately following, a course for a teacher's certificate. Students desiring to enter this branch of the profession should first take the full course of training for the teaching of general subjects in primary schools or for the specialist teacher's certificate. After a period of service with normal pupils they should qualify as teachers of the deaf by attendance at the one-year course at Manchester University. Teachers should be selected and seconded at full salary, the year should count as service for superannuation purposes, and the tuition fees of approved candidates should be paid by the National Committee for the Training of Teachers or their successors. It should be permissible for the authorities of a school or institution for the deaf to appoint teachers who have not yet undergone the special training, but they should be seconded for attendance at the Manchester course as soon as possible.

15. We recommend that the need for teachers qualified in lip-reading be met, in the meantime, by the provision of sessional or vacation classes for certificated teachers in service.

3. TEACHERS FOR SPECIAL SCHOOLS AND CLASSES

(1) The Present Provision of Special Schools and Classes

16. The education of physically and mentally defective children (exclusive of children in institutions under the administration of the General Board of Control for Scotland) is provided partly in residential schools, partly in special day schools, and partly in special classes in ordinary schools. A considerable proportion of these schools and classes provide both for mentally defective and for physically defective children.

17. The physically defective children include:

(a) Children suffering from temporary loss of health, but likely to regain normal health after being for a limited period in a day or residential school;

[page 85]

(b) Children suffering from some chronic ailment or deformity which is likely to be permanent; and

(c) Children other than the blind and the deaf, suffering from defects of vision, hearing and speech.

(2) The Present Training Arrangements

18. No provision is made for the training of teachers of physically defective children. For teachers of mentally defective children a special course of fourteen weeks is offered at the Glasgow Training Centre. Teachers of 40 years or under who have satisfactorily completed their probationary period are selected for this training by their education authorities. Full salary is paid during attendance, and it has been the practice of the National Committee to remit the fees. The course, which is organised under Article 51 of the Regulations, leads to an endorsement of special qualification as "Teacher of Mentally Defective Children".

(3) Recommendations

19. As the teacher who enters this special field may have to deal both with physically defective children and with mentally defective children, we recommend that the course of training should cover both sides. It should extend to four months, the first three months being devoted to the education of both types and the fourth month to specialisation for one type. Some instruction in the problems of residential schools should be included. The conditions of admission and method of selection of entrants should be those at present applied to teachers of mentally defective children; and, in the meantime, the course should be centralised at the Glasgow Centre.

4. TEACHERS FOR DULL, RETARDED AND PROBLEM CHILDREN

20. Increase in the educational provision for dull, retarded and problem children and, young persons in schools and junior colleges will necessitate a special training for this type of work. It could be provided either by a short full-time course for selected teachers, or by evening or vacation courses, or by both methods.

5. TEACHERS FOR APPROVED SCHOOLS

(1) The Present Position

21. There are twenty-five approved schools in Scotland, sixteen for boys and nine for girls. In four of the schools the pupils of school age attend the ordinary day schools in the area, and in some of the others this arrangement is made for certain selected pupils only. When instruction in general primary subjects is provided within the approved school it is given by certificated teachers who have had no special training for the work. The older pupils are trained in such practical occupations as carpentry, shoemaking, cookery, and gardening by craft instructors with no professional preparation. The majority of the pupils in these approved schools are seriously retarded, often by as much as two years, and a small proportion are near or under the borderline for mental defect.

22. The conditions to which we refer in paragraph 130 of the Report apply specially to teachers in approved schools; in particular there should be more opportunities for promotion to positions in ordinary schools.

(2) Recommendations

23. While we have recommended that all courses for teachers of general subjects in primary schools should include some instruction in methods of handling handicapped children, we are of opinion that additional special training is necessary for teachers of general subjects in approved schools. Such special training should include a fuller preparation in the use of individual work methods and methods for small groups, in the education of dull, retarded, and mentally defective children, in the psychology of such children, and in the technique of mental testing. Supervised teaching practice in approved schools should be included, and there should be some instruction in the conditions and problems of residential institutions. For these teachers the knowledge of social conditions and of educational and welfare agencies to which we have referred in Chapter II is particularly important. In selecting candidates for training, special attention should be paid to qualities of personality.

24. We recommend that the additional training, which should be taken by selected certificated teachers who have had a period of service in ordinary day schools, should be provided by means of (1) a three-month full-time course centralised at one of the training centres, or (2) two vacation classes of three weeks each to be attended in successive years immediately after the teacher has been appointed to an approved school.

25. Instruction in physical education in approved schools should be given by teachers with the specialist teacher's certificate in the subject. The same arrangement could be made in domestic subjects, provided that the teachers are willing to take an appropriate part in the clay to day running of the school. Instruction in art and music will normally

[page 86]

be provided by visiting specialists; and for more advanced instruction in school subjects attendance at outside schools should be arranged. Craft instruction in these schools is best given by first-rate craftsmen who are not certificated teachers, but we recommend that such instructors should take a short evening or vacation course in methods of teaching.

6. PROVISION FOR CHILDREN WITH DEFECTS OF SPEECH

26. Children with defects of speech should first be examined by a fully qualified speech therapist who may be associated with a child guidance clinic. Training for speech therapists is now available, but as such officers are regarded as members of the medical auxiliary service they do not come within the scope of our remit. After examination by the speech therapist certain pupils will no doubt be treated in child guidance clinics, while others may be sent to special schools or classes. Of those who are allowed to remain in the ordinary schools a number may require special exercises over a lengthy period, and if these cannot be carried out by the speech therapist it would be an advantage if, in large schools, there were teacher therapists who could deal with the children individually or in small groups. For the training of teacher therapists we recommend that a special course of two terms be provided for teachers selected and seconded by education authorities on the general conditions already indicated. The course should, in the meantime, be centralised at one of the training centres.

7. CHILD GUIDANCE

27. It is possible that in the future development of the child guidance service, there will be a place for certificated teachers with special training who will give assistance, either in their spare time or as part of their ordinary duties. A three-term course for such teachers has already been held at the Glasgow Centre. We recommend that courses of this kind, whose character and duration should be reconsidered from time to time, should continue to be offered and should lead to an endorsement of qualification for child guidance work.

APPENDIX IV

ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE

1. PRESENT ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEES

(1) The National Committee for the Training of Teachers

1. The National Committee consists of forty-five members elected by the Education Authorities from amongst the members of their Education Committees, and it is reconstituted after each new election of the Education Authorities. As a rule it meets only once a year, its main business in the past having been (1) to appoint a Chairman who is also Chairman of the Central Executive Committee, (2) to appoint certain members from their own number to serve on the Central Executive Committee, and (3) to receive and consider a report by the Central Executive Committee on the work of the session.

(2) The Central Executive Committee

2. The National Committee acts through a Central Executive Committee which consists of twenty-one members appointed as follows:

(1) The Chairman of the National Committee (ex officio);

(2) The Chairmen of the Provincial Committees and Committees of Management; but if the Chairman of the National Committee should be also the Chairman of a Provincial Committee or Committee of Management, the Vice-Chairman of the Provincial Committee or Committee of Management is (ex officio) a member of the Central Executive Committee;

(3) Ten members appointed from amongst their own number by the National Committee, including at least one from amongst the members of each Provincial Committee;

(4) Two members appointed from amongst their own number by the teachers' representatives on the Provincial Committees;

(5) One member appointed from amongst their own number by the representatives of the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland on the Provincial Committees.

3. Generally speaking, the Central Executive Committee, subject to any rules and instructions made by the National Committee for its guidance, exercises all the powers and duties assigned to the National Committee.

[page 87]

(3) The Provincial Committees

4. The National Committee delegates the management of the four Training Centres to Provincial Committees for the Training of Teachers, on each of which the same interests are represented. The composition of the Glasgow Provincial Committee, which manages the Glasgow Training Centre and also the Scottish School of Physical Education and Hygiene (for Men), is as follows:

(1) Eighteen members, being the members elected to serve upon the National Committee by the Education Authorities in the Glasgow Province;

(2) Four members appointed by the University Court of Glasgow University;

(3) Three members representing the following institutions:

The Royal Technical College,

The Glasgow and West of Scotland College of Domestic Science,

The Glasgow School of Art,

The Glasgow and West of Scotland Commercial College,

The West of Scotland Agricultural College.

The three members are elected jointly by the Chairmen of the Governors of these institutions (or representatives appointed by them) at a meeting convened for the purpose by the Chairman of the Governors of the Royal Technical College;

(4) Four members appointed by the Educational Institute of, Scotland from amongst persons actively engaged in the work of education in schools within the district served by the Glasgow Training Centre;

(5) Five members appointed by the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland;

(6) Any member appointed in terms of section 6 (b) of the Training of Teachers (Constitution of Committees) Amending Minute, 1934. This section provides that where it becomes necessary or expedient to discontinue a denominational training college there may be appointed by the relative church or denominational body one representative to each or any of the Provincial Committees, provided that during the discontinuance there is no other college held and managed in the interest of the church or denominational body concerned, and provided further that at the date of discontinuance there are within the district served by such Provincial Committee not less than ten schools transferred or established under section 18 of the Education (Scotland) Act, 1918, in which the teachers are required to be approved, as regards religious belief and character by the said church or denominational body.

5. The Director of Studies of each Training Centre acts as Executive Officer of the relative Provincial Committee.

(4) The Committees of Management

6. The National Committee delegates the management of the three Training Colleges to Committees of Management. The Committees of Management of the two Roman Catholic Training Colleges consist of:

(1) Five members elected by the Catholic Education Council of Great Britain, of whom one must be a woman teacher actively engaged in the work of education in schools, and nominated by the Association of Catholic Teachers in Scotland;

(2) Three members elected by the Provincial Committee for the Province in which the Catholic College is situated from amongst those of their number who represent Education Authorities;

(3) Two members elected by the National Committee.

7. The Committee of Management of the Dunfermline College of Hygiene and Physical Education (for Women) consists of:

(1) Five members elected by the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust;

(2) Three members elected by the St. Andrews Provincial Committee from amongst those of their number who represent Education Authorities;

(3) Two members elected by the National Committee.

(5) General

8. The Provincial Committees and Committees of Management are re-appointed immediately after each new election of the National Committee.

9. The Secretary of State nominates one or more of the Department's officers to act as assessor or assessors on the National Committee, the Central Executive Committee, the Provincial Committees and the Committees of Management. Such assessors may take part in the proceedings of the committees, but are not entitled to vote.

[page 88]

2. PRESENT FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENTS

10. The expenditure of the National Committee is met from the following main sources:

(1) Fees paid by students.

These are moderate in amount. For example, the fee for the three-year course for women training for the Teacher's General Certificate* wholly at a training centre or college is £30; that for the four-term Chapter III* course for graduates is £15.

(2) Grants from the Education (Scotland) Fund in respect of students.

Before the war these amounted to £20 in respect of every student in continuous full-time training throughout the session. Not more than four such annual grants are paid in respect of any one student, and proportionate grants are made for students who have been in part-time training or in training for only part of a year. Students for whom the grant is not payable (e.g., students from furth of Scotland who do not intend to teach in schools inspected by the Scottish Education Department) are normally asked to pay an additional fee in lieu of grant.

(3) Grants from the Education (Scotland) Fund in aid of approved capital expenditure.

Such grants amount to 75 per cent of the approved expenditure, which may be in respect of the acquisition of sites or buildings, the erection of buildings, the laying out of grounds, or the improvement of existing buildings, either for the training of teachers or for lodging students in hostels. A grant of 75 per cent of the rent is also paid in respect of temporary premises or playing fields.

(4) Contributions from education authorities proportional to the number of fully qualified teachers in their service at 31st March in each year.

11. Before 1st May the National Committee prepares an estimate of its income and expenditure for the ensuing financial year. From the total expenditure is deducted the income under heads (1), (2) and (3) above, together with that from other minor sources. The residue gives the amount to be raised by contributions from education authorities under head (4). In practice, the allocation is made by dividing the residue by the total number of teachers in service on 31st March, giving a quota per teacher. If the quota is £2, each authority pays a sum of £2 in respect of each qualified teacher in its service on 31st March. During the last ten years the quota has varied from £2 to £4 5s per teacher.

12. The following statement shows the amounts received from the various sources for the year 1938-39, the last year in which the figures were not disturbed by war conditions, and for the year 1943-44, the last year for which completed figures are available.

EXPENDITURE

| 1938-39 | £173,968 |

| 1943-44 | £164,561 |

INCOME

*See footnote to paragraph 6 of the Report.

[page 89]

APPENDIX V

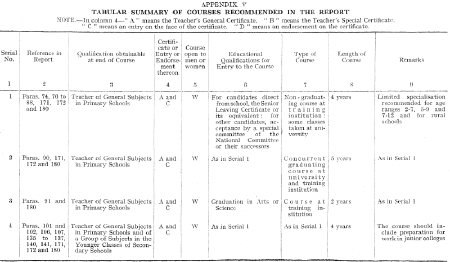

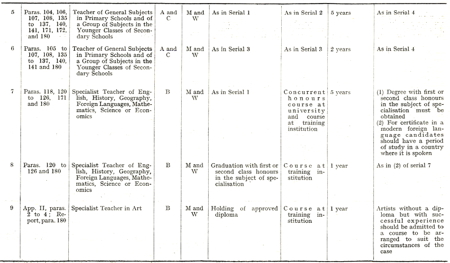

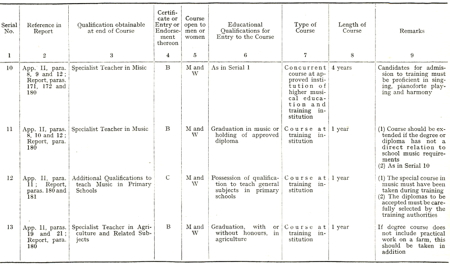

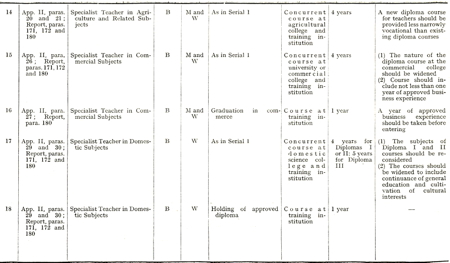

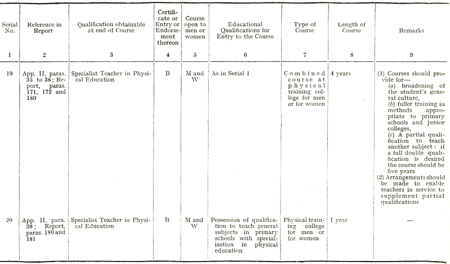

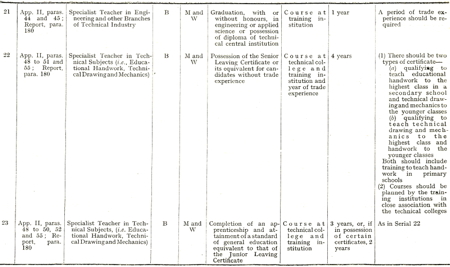

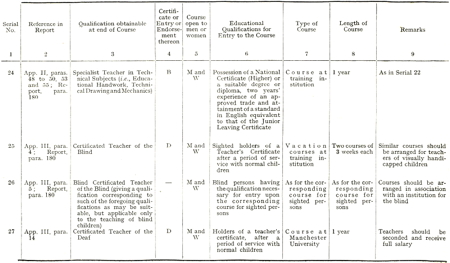

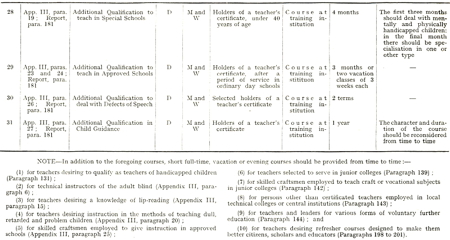

In the following pages will be found a tabular summary of the more important of the courses recommended in the Report.

The summary shows where the references to the course will be found in the body of the Report, the qualification obtainable at the end of the course, whether a certificate or an entry or endorsement thereon will be received, whether the course is open to men or women or both, the educational qualifications necessary for entry to the course, where be course is to be taken, and its length.

At the end of the summary will be found a note of the short courses recommended in the Report.

[page 90]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 91]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 92]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 93]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 94]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 95]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 96]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 97]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]