VI.

THE AIM OF THE HIGHER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: HOW BEST REALISED AND PRESERVED

In this following section of our report we propose to deal with the means by which a Higher Elementary School performs the function that we have tried to indicate. We propose also to suggest some methods for securing that a Higher Elementary School in any given case shall not deviate from its proper aim, and that as far as possible it shall perform its function effectively.

1. The Teachers

Importance of the question of teachers

We have already in preceding sections of this report referred to the important part which must in every case be played by the teachers in a Higher Elementary School of the kind that we have been at pains to describe. Our conception is based upon the character of the teaching; the

[page 38]

teachers are the essence of the school. Not only will it fall to them to work out and realise what is practically a new school, but they will he charged with a difficult kind of teaching. It is, in fact, the difference of aim governing the curriculum and methods of teaching in a higher primary school that differentiates it from a secondary school. The subjects of instruction in a higher primary school and a secondary school might even be the same, and yet in the higher primary school the difference in the length of the school training, and the difference in the kind of life and livelihood that the pupil is prepared for, must so influence the school course that the teaching in higher primary schools cannot but differ from the teaching in a secondary school. And this difference the teachers must keep in mind.

Function of the teachers in preserving the aim of the school

There is always the danger to be faced that a higher primary school, under the influence of an ambitious headmaster and staff may gradually tend to develop into a pseudo-secondary school. If it is not clear to the teachers what the function of a Higher Elementary School essentially is, energy and ambition are too likely to result in an attempt both conscious and unconscious to give the school a secondary character, and thus to miss the real point, the maximum efficiency of the school within definite limits. On the other hand, a headmaster and staff imbued with the traditions of a Public Elementary School may tend to perpetuate in the Higher Elementary School the tradition of formal routine, and of "chalk and talk" that the Higher Elementary School should make every effort to escape. Between the two dangers lies the undeveloped province which the higher primary schools of the future may be hoped to fill.

The whole of the two preceding sections of our report have gone to show what is the theoretical difference between the three kinds of school - primary, higher primary, and secondary - that are in question, but it may be well to recall how confused at present is the distinction between the two last, and to consider how much will depend on the teachers in securing that any new Higher Elementary Schools remain true to type. With new schools, which must remain true to type if their establishment (or conversion) is not to cause further confusion, and to postpone the ultimate possibility of an educational system, it is necessary that from the first the teachers should be capable of grasping the purpose that the school is to fulfil, and be able to stamp its true character upon any particular school of the kind. The conception of the difference of aim between a secondary school and a Higher Elementary School is fundamental. Yet, however clearly it may be recognised by the organising authorities, the teachers themselves have to make it actual.

The kind of teachers wanted

The teacher that is wanted is one who can teach his subject or subjects with his eyes always upon the immediate relation to practical life of the knowledge which he is trying to impart, and yet without losing sight of the purely educative value of his teaching. He must strive first of all to make the children observe and think, to develop the right habits and attitudes of mind, letting the acquisition of knowledge take care of itself. He must try to get them to see that theory and practice are bound up together, and that school work has a direct relation to life work. He must try to teach them that their knowledge may be applied and how to apply it. He must attempt, in fact, to inculcate by every method at his disposal those qualities of the character and and the mind that we have stated to be, in our belief, the most important and most desiderated [desired] in the case of children who are provided for by Higher Elementary Schools. All the subjects of instruction will take a colour from the aim of the school. What the subjects are matters far less than the way in which they are taught. If Higher Elementary Schools are to be successful, the teachers employed must be good enough to give this type of school a fair practical start, and to prove that higher primary education of the kind suggested has a reality of its own. In any case, our conception of the function of a Higher Elementary School is based upon the capacity of the teacher. He alone can preserve the salutary mean between an education purely academic and an education tending more and more to technology and trade instruction to be patched, no doubt, from time to time, as we have observed in the case of the Organised Science Schools, by the insertion of "English" subjects. The Higher Elementary School, as we understand it,

[page 39]

is not, and never should be - indeed, cannot be - a balance of "subjects"; it is a school affording a general education in continuation of the Public Elementary School course marked by a practical character. This practical character or bent must be given in the teaching. We should have to look, as a witness said, "to the intelligence of the individual teacher to affect the course". "So long as the teacher keeps in view the cultivation and training of the mental powers I do not care what occupation he puts the boy to for the purpose of attaining that end." "How do you propose", another witness was asked, "to cultivate those habits [of thought]?" "That is purely a question of the teacher. It is the way you teach rather than what you teach." With this opinion we are entirely at one.

"However good the men are", said a witness, "they cannot be too good for the sort of work I have been trying to suggest."

The question of supply: the class of teacher

It remains, of course, to be seen whether the right kind of teacher can be found. In any case, the question of the supply of teachers for Higher Elementary Schools is an urgent and pressing one. "To supply the schools before providing the teachers would be to kill the schools. The two things must go together, and it is quite useless to establish the schools until you have a prospect of getting teachers for them." How, then, are the bulk of the teachers to be obtained? Are they to be drawn from the ranks of elementary school teachers, either teaching or in training, or from the teachers in secondary schools? The evidence on this point is definite and contradictory. On the one hand, a number of witnesses have declared their opinion that the teachers for these schools should be found, and could be found, among teachers in the elementary schools. On the other hand, we had the view strongly expressed that suitable teachers must be looked for outside the elementary schools. Probably it is true to say that the character and ability of the individual teacher is the important thing, and not the class or profession of teachers, elementary or secondary, to which he is supposed to belong. The close connection of the Higher Elementary School with the Public Elementary School does indeed suggest that a man who has had experience in an ordinary Public Elementary School is likely to make a good teacher in a Higher Elementary School, in so far as he had opportunity of understanding the ways of the elementary school boy; provided that this experience has not, as a witness feared, crystallised his opinions, and rendered him incapable of adapting his mind and teaching methods to another and different kind of school.

The individual more important than the class

Our view, that in all cases the individual must be considered before taking into account the class of teachers of which he is a member, was admirably suggested by the headmistress of a higher grade school, who said: "First of all I look for a teacher who is thoroughly sympathetic with child-life and who has continued her studies since leaving college. I prefer someone who has made a hobby of some part of her work. I find such a teacher is enthusiastic, and the chances are that she will deal with the children sympathetically, and a sympathy with and knowledge of child-nature is so necessary. She must get interested in the children or she can do nothing. I am so catholic in my desire to get teachers of this kind that I have had teachers from training colleges who had been pupil teachers in elementary schools, teachers not trained at all, and teachers from secondary schools. I have, therefore, had a wide experience of varied types of teachers, and have found that, no matter what the teacher knew, if she had but little sympathy with children and no knowledge of the conditions in which they lived, she failed. Lack of knowledge of the children's surroundings is quite fatal." Such teachers are obviously not common anywhere. The fact that a man is a competent teacher in a Public Elementary School does not necessarily mean that he would make a good teacher in a Higher Elementary School. For a Higher Elementary School is needed "educated men who can approach the question with sufficient freshness of mind to learn how this teaching should be done." The rank and file of teachers, elementary or secondary, would include many who altogether lack this freshness. The teacher who is quite out of place is the sort of man picturesquely described to us by a witness: "We engaged a very excellent man to teach writing and composition. I told him to set them a test in composition, to teach

[page 40]

them to write a decent letter applying for a post, or to report on the business supposing they were left in charge while their chief was away. I actually found the man doing this: I found him telling them to apply for an advance, and saying that the best way to do this would be to ask for 'an increment in remuneration'." "I think he is a very good man", said the witness; "I have not a word to say against him in other ways; but this was his idea. The idea of another man I had was this: I wanted him to teach writing and composition, and he proceeded to do so by putting sentences on the board and making the boys copy them, e.g., Distance lends enchantment to the view. So it does - to people who have seen a good many views, but things of this sort do not interest these lads." The pre-eminent importance of awakening interest, of counteracting the formality and routine of the Public Elementary School, can only be reiterated here; we have already referred to it. "Text-book methods" and "verbal realism" must be avoided. The need is for more life in the teaching, for a more lively and adaptable spirit in the teachers.

Arguments against elementary teachers in Higher Elementary Schools

It was, perhaps, with too strong an emphasis, if the whole country be taken into account, that a witness declared the difficulty of staffing Higher Elementary Schools from the ranks of the elementary teachers. He said: "I have only to say that the greatest hindrance to the development of Higher Elementary Schools will be the difficulty of finding suitably equipped persons as teachers, and I not think we shall find such persons among the teachers of our elementary school system. If I look for headmasters, the headmasters of 20 years' experience are so impregnated with the conditions of ordinary elementary schools that it is very difficult for them to think about being freed from the trammels they have been accustomed to all their lives. In some cases their minds are divided into compartments labelled 'Standard so and so', and in each compartment there is a certain course of instruction. I think we shall have at first to pick out our staff for these schools largely from those trained in day training colleges who have had a superior education, and in future we shall have to create our own supply of teachers by training them from an early age. In this respect schools like the Battersea Polytechnic Day School may prove very valuable by affording boys an insight into industrial occupations, while they can give them a sound education as far as a knowledge of one modern language is concerned, but boys who have been through a school like Battersea Polytechnic, have attended laboratory courses for several years, and are afterwards trained in the day training college, - these are the boys I would like as assistant and head masters in the industrial departments of Higher Elementary Schools" Not that he did not recognise a number of instances where elementary teachers had proved themselves exactly the right men for schools other than elementary, and he cited several schools in London of the lower secondary type which have been largely and successfully staffed with such teachers. At the same time the difficulty exists of finding teachers "with a mind open enough to adapt themselves to any curriculum different from that to which they have been accustomed. At present the teachers acquire a certain stock-in-trade and they think this can be used anywhere." "My difficulty is to find teachers of sufficient breadth of view to act as headmasters or as class teachers, who can draw illustrations in subjects with which the boys are to be made familiar in their later technical course."

Advantages of staffing Higher Elementary Schools with elementary teachers

Nevertheless, the close connection between the Higher Elementary School and the Public Elementary School will, in our opinion, make it desirable, so far as is consistent with the aims we have outlined, to draw teachers from the elementary school system. "The Higher Elementary School", said an Elementary School Inspector, "ought to be staffed by elementary teachers of the best grade in order to maintain continuity with the Public Elementary School." As another witness said: "I think the teachers in Higher Elementary Schools should be certificated teachers under the Board of Education. These are the teachers best qualified to do the work of schools of this type." The teachers in these schools should be well acquainted with the sort of boys entering the school and with the conditions of their previous education. This experience by itself would not be enough; it would need supplementing

[page 41]

by special capacity and very possibly by special training of some kind. But the Higher Elementary School is a part of the elementary school system and would naturally draw its teachers from the system to which it belongs. We have reason also to think that elementary teachers are becoming more capable of grappling with such new problems as the Higher Elementary School presents. As the Inspector just mentioned told us, "I think there is a very remarkable change coming over the elementary teachers now. They are gradually beginning to realise that the Board has given them freedom, and a class is growing up which is trying to make use of that freedom. I have been struck very much with this in the North. Many of the teachers are working in trammels there, owing to their having antiquated head teachers, I suppose. In the old days we did our best to keep them in grooves. But nowadays many of the teachers are trying to get themselves out of these grooves. There is much more thought given to the subject now than ever there was before. The teachers are working on lines that mean making the children study. They are gradually abandoning the old regime of chalk and talk which has gone on for so long and making the children get up work for themselves and do the work for themselves. However good the teachers are they really can no more do the work of education for a child than they can do the work of digestion for the child. Gradually, I think, teachers are coming to realise the truth of this and are no longer bound by the old standards and trammels." This is encouraging testimony.

Instances of school staffing

That a very great number of the teaching posts in existing higher primary schools, whether "Higher Elementary School" or "Secondary School" or "Higher Grade School" are held by teachers trained for the work of elementary education is well known. As instances, we may cite the case of a Municipal Secondary School, where nearly half the teachers, two out of every five, are certificated; or of a Higher Elementary School, the headmaster of which informed us that all the regular staff, amounting to eleven, held the Board's certificate. None of these men have taken a degree, though all have passed some examination leading to a degree. Of the four mistresses in the girls' school, forming a part of this Higher Elementary School, one is a graduate of Dublin, one obtained First-Class Honours in History at Oxford, one is L.L.A. of St. Andrews, and the fourth has had three years' training. As a rule, the teachers in this school have had experience in a Public Elementary School previously. Such facts point to our conclusion that the bulk of the teachers should come, and will come, from among persons certificated by the Board, that they should be the best of their profession, but that the staff of a Higher Elementary School need not necessarily be confined to one class, any more than is the present staff of lower Secondary Schools and existing Higher Elementary Schools. They should not, as a witness said, be "a separate caste". Indeed, a certain mixture of elements in the staff, controlled by a competent and imaginative headmaster, may be in itself desirable as likely, through the interplay of varying ideals, to produce a more vigorous and flexible unity.

Benefit to elementary school profession generally

And there is another strong though indirect reason for appointing elementary school teachers. As an Elementary School Inspector pointed out, these posts "would be the plums of the public elementary scholastic profession, and I think they would help to give a general lift to the profession, give them something to aim at, something to hope for, and something to work for. Of late we have been taking away from the elementary teachers all their higher and more interesting work: we have taken away from them virtually the specific subjects, and we have taken away from them the instruction of pupil teachers. We are keeping them down now to an entirely lower level of work - whether rightly or wrongly I will not say - but still, we are doing it; and I am inclined to think it is a mistake that it should be universally done. I think there ought to be something for them to look up to and to look forward to and to aim at. I think the establishment of Higher Elementary Schools would give them a renewed interest in life, and I think the elementary teachers who had got university degrees would probably be the men who would be the more suitable for this kind of work."

[page 42]

If we want good teachers we must give them interesting work; if they are to interest their pupils the work must first interest them.

Possible steps towards securing a supply

It is clear then that the best elementary teachers will furnish the greater part of the personnel. Can any steps he taken to train them specially for the work?

However desirable in theory, an elaborate system of training will for the present, at any rate, be unnecessary since the demand for Higher Elementary School teachers is likely to be small at first, and gradually, but only gradually, to grow larger. It is not probable that many entirely new schools will he established in the near future, though we believe that when new schools, other than elementary, are required, a Higher Elementary School will in a very great number of cases be more useful than a secondary school. "I do not anticipate a very large demand ... I think the need could be met without much difficulty", an Inspector said, and he was speaking of schools of a rather more definitely "commercial" or "industrial" type than we should as a general rule be inclined to encourage, except possibly in the larger towns. Another Inspector held a similar opinion - the supply would equal the demand. "It would be", he said, "a case of supply and demand. The greater the demand and the more the posts are worth holding the more teachers are likely to look forward to them, and aim at them themselves." The system of Higher Elementary Schools, however, "would take a long time to establish: It "will only arise little by little". Thus, at present, we may hope that among the teachers actually serving there would be a sufficient number capable of effective work in a Higher Elementary School. Certain of them, no doubt, would find it necessary to acquire additional qualifications in knowledge. For instance, "if they were not good enough to start with, they would have to educate themselves to teach more advanced mathematics than in the ordinary elementary school, and so forth." But such qualification would be acquired individually and automatically if the end were worth the trouble. "If they once had these prizes to look forward to the teachers would take more pains to qualify themselves." The realisation of the teaching problem presented in a Higher Elementary School, which is in itself of paramount importance, need not, we think, mean more than a moderate intellectual effort in the case of teachers who have preserved some mental suppleness. " Yes, we can get people of sufficient breadth of mind to learn the work, certainly," an Inspector assured us. "I have seen teachers learning this work in evening schools, and once they have grasped the problem they can do it." For the teaching of scientific subjects good material would probably be found among men trained as elementary teachers, who have yet been able to take science degrees at some of the newer universities, and may now be occupying posts in so-called secondary and Higher Grade schools.

Some practical suggestions

At the same time it may be useful to indicate some possible methods of adding to, or modifying, the training of teachers in view of the needs of Higher Elementary Schools that are likely in the future to be set up in larger numbers:

(i) The training colleges might, with advantage, institute lectures in the aim and problems of Higher Elementary Schools, and arrange to supplement and illustrate this course by practice, where possible, in schools which already approximate to the type of Higher Elementary School that it is proposed to establish. Even if they do no more, at any rate the training college authorities should keep in mind the possibility of such posts and the qualities fitting teachers to hold them.

(ii) In the case of teachers with a definite bent towards science and technology, the third year of training contemplated in section 4, page vii, of the Training College Regulations (1905), could well be devoted to the purpose of a special course in connection with suitable technical institutions or polytechnics. In some cases this third year might, with advantage, be allowed, not, as normally, immediately after the two years' course, but as in the case of a third year abroad, after a period of teaching experience. At the

[page 43]

present juncture it would be more important to allow it for teachers already engaged in schools who are willing to give the necessary time. Similarly the policy suggested in section 21 (a) and (b) of the same Regulations could also be utilised and the principle extended. Those students who are exempted would he enabled to specialise in part with a view to technical studies. In every case one definite form of skill should be combined with a varied acquaintance with the problems and prospects of industrial life. The main object to secure is the development of a habit of mind and intelligent interest in such problems as they arise.

(iii) It is also suggested that an additional year spent in the study of industrial and commercial problems in the actual workshops and places of business concerned would also supply a valuable means of supplementary training, for which facilities might be secured. The evidence on this point is, however, conflicting. While one witness declared "you will have to have teachers who are trained as teachers all round, but they must have some knowledge as to the occupations in which those boys (and also girls in certain kindred subjects) are to be trained", and expressed the belief that "employers of labour, whether in offices or in manufactories in the textile trades or in the iron trades, would welcome a request from young persons who desired to enter their establishments for the sake of observing things on a large scale, or for the purpose of making inquiries"; practical workshop experience was not thought essential by another witness; though the teacher need not be a man with practical experience "he should be a man possessing or capable of an intelligent knowledge of what goes on in workshops". An inspector, again, stated that he did "not think the ordinary certificated teacher, unless he has had some practical experience of the work in which artisans are engaged, or has had some practical experience on commercial lines, would really be a satisfactory teacher in this type of school". But it must not be forgotten that our conception of such a school is of a school less technical and less specialised in the subjects of its curriculum (though not in its aim) than the sort of school that we believe some of our witnesses had in mind, and that the manner and method of teaching are, in our view, of far greater importance than any practical experience on the teacher's part of the actual conditions in the factory or business office; provided that the teacher is a person of some imagination, and is not hidebound by a purely academic tradition. We believe that in this country, as in Scotland, much might be trusted to "the intelligent teacher who has got his eyes open". The higher the standard of general intelligence produced by the training' colleges, and what comes before the training college, the easier it will be to staff Higher Elementary Schools.

For the teaching of special technical subjects, if in any case such subjects are sanctioned, special provision will always have to be made.

An attempt at classification

Classified, then, with regard to educational antecedents, the teachers in Higher Elementary Schools would fall into classes somewhat of the following kinds:

*(i) Persons who have been trained as elementary school teachers and whose special ability and capacity for adaptation, as shown by their actual service in elementary schools, fits them for appointment in Higher Elementary Schools. Some of them may possibly be graduates.

(ii) Persons who very possibly have not passed through a training college but have had experience in lower secondary schools (Division A or B schools or municipal secondary schools), possibly in some cases graduates, probably of the newer universities. These teachers

*As a matter of fact, the bulk of the masters and mistresses in Higher Elementary Schools will probably be drawn from this class.

[page 44]

may be expected to have picked up from their experience a knowledge of the difficulties and problems to be met in such schools.

(iii) Persons who have gone through the regular training college course and have availed themselves of the suggested facilities for a special study of the problems presented by Higher Elementary Schools and have taken part of their practice in schools of this kind. Some of those teachers might be appointed direct into Higher Elementary Schools upon obtaining their certificate. For the rest of their training as teachers they would depend on the help and direction that the headmaster might be able to give them.

(iv) Persons who have been trained in a training college, with a view to possible appointment in a Higher Elementary School, and have for this purpose spent a year in a polytechnic or in a workshop or house of business.

(v) Persons who may be appointed to teach "special" subjects such as advanced carpentry or some kind of metal work, or the more advanced branches of housecraft. Some of these will be men and women who have taken up teaching comparatively late after experience in practical life. They may, nevertheless, make good members of the staff, acting in co-operation with the regular teachers.

More differentiation of teaching function and more money needed

Before concluding this section of our report we would draw attention to two points remaining - the desirability of teachers as far as possible confining themselves to one subject or group of related subjects, and, secondly, the need of expending more money on the adequate training of teachers and in the payment of higher salaries. There ought to be, as an Elementary School Inspector said, in reference to the teacher's function, "more specialisation", less expectation that the teacher should teach everything, more opportunity for a teacher to take the children in what he may most affect. As to the second point it must be clear that the better education of teachers will mean increased expenditure. "I think a large expenditure will have to be incurred in England yet", said a witness, "in cultivating and training teachers properly." We do not think that any expenditure incurred for this purpose, can, if it be rightly administered, constitute anything but a most productive national investment.

2. The Curriculum

The question of curriculum, though less important than the question of teachers, is, of course, an important one and we have already indicated in a broad and general way the lines that we believe the curriculum of a Higher Elementary School should take.* It is conditioned chiefly by its close connection with the Public Elementary School curriculum which it develops and from which it evolves, by the shortness of the school course, and by the need of giving a practical bearing to the school instruction as a whole. In the "Suggestions for Teachers" the Board have already discussed the teaching of the subjects referred to below and their educative value. The suggestions appear to us to be as applicable to Higher Elementary Schools as to other elementary schools, and consequently no attempt is made in this report to traverse the ground which the suggestions have already so admirably covered.

The curriculum to include -

(1) Humanistic subjects

The curriculum must, as we have already said in Section III, be simple and well-defined in range. It should in all cases give a prominent place to the study of English, to the language as a means of expression, both oral and written, and as an aid to precision of thought. Exercises in practical forms of composition, letter and précis writing, and frequent practice in oral composition, to which we attach great weight, should be included. It is of

*The remarks here made are to be read in connection with our observations in Section III of this report. We take the term "curriculum" to mean, for our present purpose, the subjects taught and the proportion of school time given to each.

[page 45]

the first importance to cultivate the power of expression; and not only the "English" part of the curriculum, but the "science" part also, may be made a means to this end. The study of the language will imply some introduction to English literature, to which the school course must look for the greatest part of its humanising influence. Probably there will be little time to devote to literature as such, but its value as a means of widening interests and sympathies and as indicating a field for further reading, cannot be over-estimated. As subsidiary subjects will be included some study of history and geography, though the amount of time given to these subjects will necessarily be limited. Both are closely correlated, and may often be taught as one subject. The history teaching should aim at giving the children some notion of the past as a background to the present, illustrated more particularly from the history of this country and of their own district. The geography teaching should indicate the way in which physical conditions affect political and social relations in given places. In commercial centres these subjects might be so handled as to throw light upon the commercial activities of the place.

(2) Science subjects

English language and literature, history and geography, will make up the humanistic part of the course. The scientific part will include arithmetic as applied to practical calculations, and taught in conjunction with the elements of algebra and the principles of geometry - both of these branches being correlated with one another, and their application to practice kept constantly in mind. Account-keeping should, as we have said, take the place of any instruction in a particular system of book-keeping. Graphical methods of calculation are likely to be especially useful to children attending Higher Elementary Schools, and in all schools the elements of mensuration should be taught. Besides this instruction in mathematics, the scientific part of the curriculum should include instruction in elementary natural science, not so much as "chemistry", or "physics", or "mechanics" but as some elementary practice in the methods by which we arrive at a knowledge of the commoner chemical and physical properties of bodies. The teaching of this elementary science may well be illustrated where necessary by simple and obvious references to the application of chemical or physical or mechanical theory in industries or occupations with which the children are familiar or with which they are likely to become well acquainted. Simple experiments, performed where possible by the children themselves, should accompany this theoretical instruction. In all cases, however, it is desirable that a beginning should be made with concrete objects, and not with abstract principles, with common substances or things rather than with elements. In the country it may often be well to use nature study as the main channel of this sort of teaching. But whatever the subject, "nature study", or "chemistry", or "physics", or "mechanics", the important feature of the science teaching will consist in showing the children the relation of these sciences to many everyday things and processes.

(3) Manual work

There remains manual instruction. Here again we desire to emphasise our view that manual instruction, whatever form or forms it may take in a particular school, should always be regarded as one subject, intended to train generally the use of the hand, eye, and brain together, and not primarily as several separate subjects, that is, as a means of instructing the children in "carpentry", or "clay-modelling", or "lathe-work", or any other special skill, except in quite a subordinate sense. This is, of course, analogous to what has been said about the teaching of literary subjects or of science in the Higher Elementary School. There should be no rigid line of demarcation separating the subjects of manual instruction. The aim of the teaching of each is identical, namely, to practise the hand and eye together, and it is hardly material from this point of view which branch of manual instruction is taught and which branch is not taught. Other reasons, however, such as the greater degree of manual control needed for working in metal, and questions of expense, will always be present to affect the arrangement of the curriculum in practice. In the third year, for instance, it may be desirable to add metal work (filing, chipping, elementary lathe-work) to the wood-work and clay-modelling of the first two years. This, however, is a matter upon which generalisation is impossible. It is of course

[page 46]

very important that children who are likely to go into industrial occupations should have learnt to work with their hands, and have acquired some power of using tools. Even in a Higher Elementary School of a "commercial type" some manual instruction should be included in the curriculum. Probably in the majority of schools eight hours a week of manual instruction in the first two years, and rather more in the last year, would be the proper amount; but, discretion in this matter must be left to the teachers and the Local Education Authority. Under manual instruction we include drawing, both freehand, model, and, to a lesser extent, geometrical and mechanical - in fact, all those subjects which train the use of the hand, eye, and brain together. We hold very strongly that, as in the case of the rest of the curriculum, as much correlation as possible between the various subjects and parts of subjects should be encouraged. To drawing we attach great importance as affording excellent training in the use of hand and eye together, and for the opportunities it offers of evoking and developing artistic feeling as well as for its practical usefulness in all branches of constructive work.

Suggestions as to time to be given to each

It is, as we have said, impossible, and would be undesirable, owing to the varying needs of different schools, to suggest actual time tables; but for the first two years at any rate, in a week of 28 to 30 hours, 8 or 10 hours might be devoted to religious instruction, literary subjects, and class singing, 8 or 10 hours to mathematics and science, 8 hours to manual work and drawing, and at least 2 hours to physical training - the last carefully adapted to the age and physical condition of the children, more particularly in the case of girls, in whose case physical exercises should always be conducted, or at any rate supervised, by a woman, possessed, where possible, of special qualification. When a modern language is taken, less time probably should be devoted to mathematics, science, and manual work; no deduction from the time given to literary subjects can be afforded to make room for so special a subject as a modern foreign language.

Domestic courses for girls

The domestic course for girls should he planned with a view to the development of the pupils' interest, intelligence, and skill in the management of a home. Such development implies:

(1) A sense of duties in domestic matters shown in a desire to serve and to take responsibility.

(2) A scientific attitude of mind in dealing with domestic problems as they arise, i.e. a practical consciousness of cause and effect in common things;

(3) Sufficient skill and particular knowledge in the special domestic arts, as cooking, washing, house cleaning, needlework, and house finance.

The first consideration suggests the advantage of associating the Domestic Course with the actual service of dining and housekeeping. This is also desirable as conducive to practice in thrift.

The second consideration points to courses of study dealing with common domestic problems, and indicating how they may be solved. This course of domestic science, or, as it might he called, "Studies in Domestic Problems", subdivides itself along natural lines of cleavage into:

(i) Hygiene, including problems of ventilation, clothing, food values, etc.

(ii) Domestic Economy, including problems of heating, lighting, different kinds of cooking and cleaning, etc.

(iii) Domestic Finance, including accounts, comparison of prices, etc.

The usual practical course should be amply provided in cookery, washing and ironing, care of a house, needlework, and thrifty housekeeping, with accounts.

In the country a love of gardening may be encouraged, and a practical course of instruction may with advantage be provided. This should include the cultivation of flowers as well as vegetables. Much liberty should be left to the schools in the proposals of syllabuses for approval, but every scheme of housecraft teaching should provide for the triple educational development suggested above.

[page 47]

3. Other Considerations

Conditions of admission and leaving

We are disposed to approve the present regulations in section 39 of the Code, limiting the admission to Higher Elementary Schools to children who are not less than 12 years of age at the date of admission, and have been for at least two years previously in a Public Elementary School. But we think that both these limits might "be relaxed" in special cases by H.M. Inspector, who should also have the power to disallow the admission or discontinue the attendance of any pupil who is clearly unfit to proceed with the course. Where a child is admitted by special permission at the age of 11 he should he allowed to stay to the age of 15 plus, which would be the ordinary leaving age for children at these schools.

It may be observed in this connection that the awarding of Junior County Scholarships in some local areas at the age of 11 plus might make it more convenient to admit children from the Public Elementary School to the Higher Elementary School before the age of 12. The scholarships are tenable in Secondary Schools. To admit children to the Higher Elementary Schools at the age at which others pass into Secondary Schools might be of advantage in the organisation of the Public Elementary School and its work. In such cases a preparatory department consisting of children (on whom grant at the Public Elementary School rate and not the Higher Elementary School rate might be paid) between the ages of 11 plus and 12 plus would feed the Higher Elementary School. Children who at 12 plus showed themselves unfit to continue the course would remain in the Public Elementary School.

Entrance examination

It is not intended by the Code that Higher Elementary Schools should be open to all children who have attended a Public Elementary School to the age of 12, but only to those who show that they are capable of profiting by a course of further instruction. Some test is therefore required to make selection possible, and all the evidence that we have heard is in favour of employing one. The headmistress of a Higher Grade School pointed out that originally the arrangement had been to draft all the scholars in Standard VII of contributory schools into the Higher Grade School; the arrangement, however, proved impracticable, and an entrance examination was instituted. In Scotland, admission to an Intermediate School is limited to those who pass a qualifying examination, which cannot be taken before the age of 12, and is "simply a test of a reasonably complete elementary education". Before admission to the Higher Elementary School in Hornsey children must pass a written examination, though some weight attaches to the opinions of the teachers in the Public Elementary Schools from which the children come. Every child within the age limit in neighbouring Public Elementary Schools receives an application form. Admission both to the lower and upper divisions of the Municipal Secondary School in Scarborough is gained by examination. All the children in Scarborough in Standard V between the ages of 12 and 13 are examined by the headmaster of the Municipal Secondary School, in conjunction with the head teachers of the respective schools. Similarly in the Manchester Higher Elementary Schools a qualifying examination is held.

The evidence of H.M. Inspectors has, however, suggested forcibly that the opinion of the teachers in the Public Elementary Schools is a more satisfactory basis of selection than an examination. An inspector was asked whether he thought that the teachers could be trusted to nominate only those who were fitted. He said: "Whatever you do you will get some unsuitable children, but by nomination you will get far fewer than by any other system." He was willing at the same time to combine the system of nomination with that of examination. Another Inspector for Elementary Schools preferred examination.

Other educational experts, on the other hand, thought an examination desirable.

On the whole we think that the best test of capacity is a simple qualifying examination in the ordinary Public Elementary School subjects, conducted by the head teacher of the Higher Elementary School in consultation with the heads of the respective Public Elementary Schools, the results being submitted to H.M. Inspector or some properly qualified officer of the Local

[page 48]

Education Authority. The examination should be founded entirely upon the curriculum of the Public Elementary School, and in examining the children and deciding upon the results of the examination, importance should be attached to a report by the head teacher of the Public Elementary School on the character and aptitude of each child examined.

Length of course

The length of the course in a Higher Elementary School is very important as a factor closely connected with its aim and function. As a rule, the course in a Higher Elementary School should extend over a period of three years, a fourth year, as suggested in the Code, being permitted only in exceptional localities where the conditions of local employment make an extension of the course desirable. Every precaution must, however, in our opinion, be taken to secure that the sanction of a fourth year in a number of individual cases has no tendency towards altering the character of the school indirectly, except where such extension may be permitted with the express intention of thus taking a preliminary step towards the creation of a Secondary School, if such a school prove to be needed, on the basis of the existing Higher Elementary School. We think that the inspector, in exercising the power mentioned in section 40 (iv) of the Code, should be careful to exercise it only in cases where the circumstances of the locality justify the organisation of a fourth year's course.

Parents' undertaking

In order that the Higher Elementary School shall be able to exert the fullest influence on its pupils, it is desirable that it shall be able to count on each child's continuous attendance during the three years of the course. We have considered whether it would be feasible to require from parents, as a condition of the admission of their child to a Higher Elementary School, some undertaking pledging them to keep the child at school for three years. We have been struck by the fact that in Scotland, in many districts, the children are not admitted to such a school except on the undertaking of the parents that they will not ask to remove the child before the age of 15. And it is reasonable to hold that money expended by the State upon a school giving a definite three years' course is not expended properly if the children do not pursue the course continuously for that period. "I think", said one witness, "that when we offer education to children free, we have the right to ask the parents whether, in return for this privilege, they will express the intention of allowing the children to remain throughout the course, so as to avoid the waste of public money." Yet it would hardly be possible to exclude children whose parents were unable to make such a declaration, and there are reasons for thinking that even a part of the Higher Elementary School course would not be altogether without value for pupils ready to profit by it after a course of instruction in a Public Elementary School. A child who leaves the Public Elementary School and enters a Secondary School for a comparatively short period can turn this additional schooling to very little profit, since so much time is occupied in becoming accustomed to his new surroundings, and almost as soon as the adjustment is made he leaves. The case is different when a child enters the Higher Elementary School. As an Elementary School Inspector said, "Even if they were only able to stay a short time in the Higher Elementary School, it would not matter so much; they would be working on their own lines; they would not have that break of gauge which is involved in transplantation from Elementary to Secondary Schools. ... Every month spent in the Higher Elementary School is of use, for the child has not been transplanted." To insist on a stereotyped undertaking might tend to deprive many children of this advantage, but where possible some such undertaking should be required. A witness, who considered that children remaining only to the middle of the course in a Higher Elementary School nevertheless gained substantial advantage, recommended that parents should be circularised, as in the case of her own school, and should be asked whether "they are prepared to keep the children at school for a certain length of time". This declaration the parents sign before the children are admitted. She agreed that in some cases it is beyond the parents' control to fulfil the promise. If it could be definitely ascertained that a child was not intended to remain at school for the full three years, then it would be desirable that the child should be excluded. To ascertain this, however, is impracticable, and the greatest amount of security that appears to

[page 49]

be possible would probably result from instituting a form of declaration, possessing of course no legal sanction, stating that it is the parents' intention to keep the child at school for the whole course, and that they will make all reasonable efforts to do so. It is true that some witnesses were generally for excluding all children who could not produce a parents' declaration, though even they admitted some qualification; but we are of opinion that bearing in mind the confessed (though proportionately small) value of even a part of the Higher Elementary School course, and the necessity of establishing Higher Elementary Schools under the most favourable auspices, it would be inadvisable at present to go further than what is suggested.

Size of classes

The object of the Higher Elementary School, fulfilled as it can only be by means of good teaching, requires that the efforts of the teachers should not be neutralised, as we believe is frequently the case in Public Elementary Schools, by the too large size of the classes. There is no educational reason why a class in a Higher Elementary School should be larger than in a Secondary School, and we think that in no case in a Higher Elementary School should the numbers in a class exceed 40. From an educational standpoint this number is in itself too large, but the claims of expense cannot, unfortunately, be ignored. It is to be hoped that this maximum will seldom be reached. In the upper classes it is desirable that the numbers should be less than those in the lowest class. No teacher, we think, should ordinarily be responsible for more than one class, though occasionally it may be found possible or even convenient to instruct two classes together.

Co-operation with employers

"If special schools", said an Inspector of the Board, are to be "really successful, if they are to be of practical use in the towns in which they are to be established, it is essential that great pains should be taken to induce employers to take an interest in them; ... nothing can of course be done unless the hearty co-operation of employers is secured." With this opinion we are thoroughly in agreement. The organising authority on the one side attempts to provide the employer with the right kind of material, and the employer on the other may be fairly expected to co-operate with the authority in his own interest. It will be useless to establish Higher Elementary Schools having a three years' course with the express purpose of fitting boys to enter trades and factories if employers refuse to take them older than fourteen. As another Inspector said, "It is no good developing Higher Elementary Schools to carry boys to the age of 15 if the only job they can find when they leave school is in an office. In Manchester, for example, a number of firms will not take an apprentice if he is past 14. In that case it is no good giving a boy specialised instruction to the age of 15 and then turning him out with an education which fits him for work as an artisan if he is driven by force of circumstance to go into an office." Some co-operation of this kind already exists, and is being extended. It is to be supposed that by consulting the needs of employers as far as practicable some system might be developed with this end in view. We notice with satisfaction that the Government works at Woolwich and Enfield, among others, encourage the education of the lads they employ, and that several of the most important engineering firms - Messrs. Mather and Platt, Messrs. Brunner Mond, and the Great Eastern Railway Company for example - have made practical provision for the industrial training of their younger employees. They encourage them also to attend evening schools. On the other hand a number of the smaller firms are less enlightened, and would appear to be as apathetic as many of the parents. This at any rate was the opinion of a Manchester witness of considerable experience. There is thus every need that, simultaneously with the establishment of a Higher Elementary School, efforts should be made by the Local Education Authority to enlist the sympathy and help of employers, and to create an intelligent public opinion favourable to this type of school and cognisant of its intended function. A close connection between the school itself and a circle of employers is much to be desired - an extension of the custom mentioned by one witness, who told us that the heads of several large business firms in his town invariably sent to him for boys. Nor do we believe that organised co-operation is likely

[page 50]

to present more than ordinary difficulty if the employers are approached in the right way, and if the Higher Elementary Schools fulfil their function strictly. It is imperative, as one witness pointed out with regard to trade schools, that the confidence of the employer should be secured, and it will be one of the chief duties of the headmaster or head-mistress to use all practical methods to secure it. We would refer to the patronage committee (comité de patronage) which is attached in France to every école primaire supérieure. This committee watches over the practical interests of the pupils and their good conduct in school; it affords its patronage to them, and concerns itself with obtaining posts for the most deserving pupils when they leave.

School record, and leaving examination

Further, in view of the close connection that such schools ought to maintain with employers, it is desirable that, in Higher Elementary Schools or Supplementary Courses, a "School-record" corresponding to the French livret scolaire should be instituted, and a certificate granted to all pupils who satisfactorily complete the full three years' course. For the purposes of this certificate it might possibly be desirable to hold some kind of leaving examination, but this does not appear to us to be essential. There can be no doubt that a satisfactory school record closing with such a certificate would soon come to be accepted by employers as testimony of a good school education. The school record and certificate would constitute an educational passport in districts other than that where the school itself was situated.

We should, however, deprecate the taking of external examinations such as those conducted by the Oxford and Cambridge Delegates for Local Examinations or by the College of Preceptors. This opinion, and the reason for it, were given by an Inspector when he said: "I think we ought to set our faces rather strongly against children in these schools entering for the Oxford and Cambridge Local Examinations, for I think that these examinations are not suitable for these children. They put a wrong ideal before the quasi-Secondary Schools." "The Oxford and Cambridge Preliminary and Junior Examinations are meant to test boys for an education which is to be prolonged considerably more than the education of boys at these schools, and they are not arranged at all with a view to boys leaving school as soon as they have passed the examination ... many masters and mistresses have told me that they would be glad to be allowed to give them up." The taking of examinations of this kind is apt to influence unduly the character of the curriculum and to act in the direction of producing a pseudo-Secondary school. It tends to encourage the deviation from true type which has been so inimical to the Higher Grade Schools. These reasons are in themselves sufficient to justify our view, which is also supported by the now familiar arguments against external examinations as such.

Name

Several of our witnesses have been interrogated as to whether they approved or disapproved of the term "Higher Elementary" School, and with one exception they have declared against it. The Inspector who favoured it did so on the ground that "it is a good thing to call things what they are. He thought the name would tend to make clear the distinction between Higher Elementary Schools and Secondary Schools. It is a school for which the ordinary Elementary School is a preparation, and is, therefore, not unjustly to be called a Higher Elementary School. The name, however, was opposed for two reasons: in the first place, because it is important that there should be no doubt as to the character of the school, more especially in cases where a Higher Elementary School might possibly be of a very definite type, and where it might consequently be of advantage to call the school an "artisan" or "commercial day school". We believe, however, that these terms are too limiting, and that no school (or very few) should be of so marked a character as to be thus designated without undue emphasis upon a particular aspect of the school. The name was objected to in the second place because, as two witnesses alleged, a prejudice exists in the minds of some parents and some employers against schools called "Elementary". It is said that some employers refuse to employ boys who have not been to a school called "Secondary". Further, schools that have been called "Secondary" may find less objection to necessary removal from that class if the class in

[page 51]

which they may be re-graded is not designated by a term which contains the word "Elementary".

It is difficult, however, to formulate a satisfactory name. "Intermediate" suggests itself, but is open to the serious objection that the Higher Elementary School is the completion of the Public Elementary School course and not "Intermediate", as the term would seem to imply, between the Public Elementary School and any other organised course of day-school instruction; particularly it is not intermediate between the Public Elementary School and the Secondary School. In view of the fact that it continues the Public Elementary School course, we would suggest that "Day Continuation School" (on the analogy of "Evening Continuation School") would be a preferable term.

The question of fees

The fees to be charged in a Higher Elementary School should be fixed by the Local Education Authority, but no fee should exceed 9d. [4p], or, where Fee Grant is paid, 6d. [2½p], a week. We think, however, that in schools charging fees a considerable proportion of the school accommodation should be open without charge to duly qualified children of the wage-earning classes. In schools situate in the poorest quarters or towns all the places might be free.

Returns by Local Education Authorities

Finally, we would suggest that the Board of Education should ask the Local Education Authorities conducting Higher Elementary Schools to furnish the Board with annual returns showing, as far as possible, the occupations into which pupils from these schools have passed. We believe that a return of this character will be very helpful in securing that a Higher Elementary School continues to perform its function in relation to the classes and callings for which it is intended. It will further aid the organising authority in determining whether in any case a Secondary School should be developed out of the existing Higher Elementary School.

W. HART DYKE,

Chairman.

May 24th, 1906.

HORACE E. MANN,

Secretary.

[page 52]

NAMES OF MEMBERS OF THE CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE

The Right Hon. Sir William Hart Dyke, Bart. (Chairman).

The Right Hon. A. H. Dyke Acland.

Mr. Arthur C. Benson.

Mrs. Sophie Bryant.

Sir Michael Foster, K.C.B.

Mr. Ernest Gray.

The Right Hon. Henry Hobhouse.

Miss Lydia Manley.

Dr. Norman Moore.

The Venerable E. G. Sandford.

Mrs. Eleanor M. Sidgwick.

The Reverend Dr. D. J. Waller.

Mr. T. Herbert Warren.

Mr. Sidney H. Wells.

The Reverend James Went.

Horace E. Mann (Secretary).

[page 53]

Appendix A

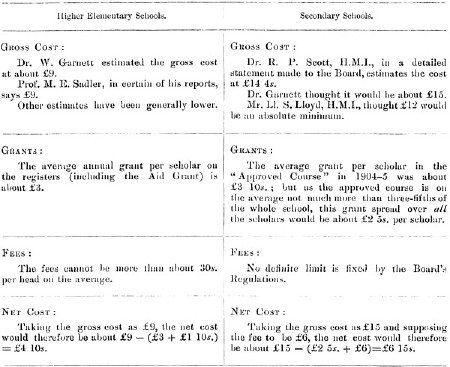

COST OF HIGHER ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS

(i) COST OF BUILDING

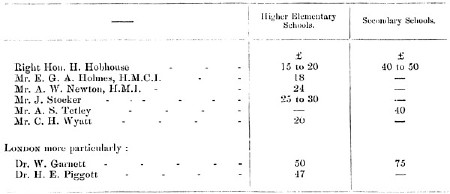

The following estimates as to the cost per head of building Higher Elementary Schools and Secondary Schools have been supplied to the Committee:

[click on the image for a larger version]

(ii) COST OF MAINTENANCE

[click on the image for a larger version]

(ii) COST OF MAINTENANCE

The following table is based on the more definite of the estimates as to cost that are available, and attempts to show comparatively the approximate gross and net cost of conducting Higher Elementary Schools and Secondary Schools (exclusive of Sinking Fund and interest on capital expenditure), with the amount of the grants and the fees in each case:

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 54]

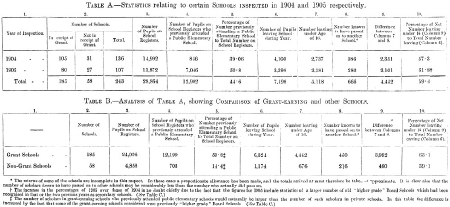

Appendix B

TABLES (PREPARED BY THE DIRECTOR OF SPECIAL INQUIRIES AND REPORTS) SHOWING (1) NUMBER OF PUPILS LEAVING CERTAIN LOWER SECONDARY SCHOOLS UNDER THE AGE OF 16, AND (2) NUMBER OF PUPILS ON THE REGISTERS OF THESE SCHOOLS WHO HAD PREVIOUSLY ATTENDED PUBLIC ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

The following Tables are compiled from statistics supplied in connection with inspection by the Board of Education.

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 55]

TABLE C. STATISTICS of the OLD "HIGHER GRADE" BOARD SCHOOLS (now recognised as Secondary) included in TABLES A and B

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]