[page 141]

MISS HARRINGTON'S REPORT

Methods adopted. The methods I have adopted in endeavouring to ascertain the information required for this report include:

1. Personal observation during visits.

2. Comparison of results by tests in the "three R.'s"

3. Questioning selected children, with a view to determining intelligence and power of expression.

4. Reference to opinion of teachers, head and assistant, as persons placed in best position to judge of value of results.

5. Comparison of statistics obtained from admission and attendance registers, with Head Teachers' help.

Before proceeding to give in detail the conclusions derived from this inspection, I wish to point out that no inspection, consisting merely of two or four sessions, can adequately determine many of the points under discussion. A knowledge of the circumstances of the parents is required, as well as of the home life of the child, and its physical and mental character which can only be the result of an intimate daily acquaintance lasting for weeks or months. The teachers alone have, necessarily, from their position, this knowledge. They alone have the opportunity of judging the exact state of the child's intelligence on admission to the school; they have more or less acquaintance with its home environment, to which so many modifications are due; they have experience of its average performance of tasks, and can trace, day by day, the development of its powers and the advantages and drawbacks it meets with in health or character. They are, therefore, the experts to whom we must go for any real decision as to whether, for example, the child gains or loses by early admission, and how it differs from those admitted at five or six years.

What do the teachers say? A great many of the more experienced teachers consider three years of age much too early an age for children to begin their school life, particularly under the present conditions, when reading, writing, and number are expected to be taught even to the youngest babies. Many would willingly, for the child's sake, shut the school doors to children under four years of age, and the majority agree, that children of average intellect who start at five years of age are quite as ready to take up Standard I. work as children who start at three years. In fact, it is the common practice of teachers to place children of five years of age in the so-called five years old class.

Statistical Evidence. According to the Official Returns of one large County Borough for the month of August, 1904, there were 7,079 children under five years of age in daily attendance out of 9,995 such children on registers. Again, in another County Borough, 1,106 children under five years of age are in daily attendance out of 1,500 on books.

[page 142]

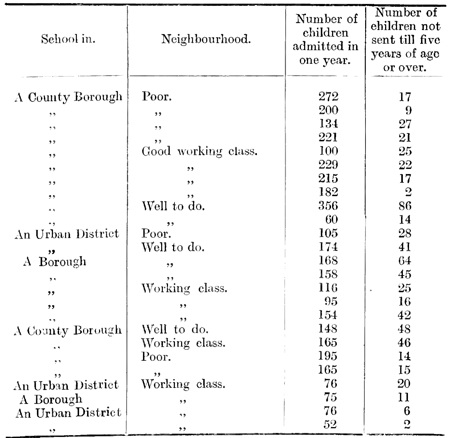

The following table will show the small proportion of children admitted at five years of age, as compared with children admitted under five years of age.

In several schools in manufacturing Urban Districts all the children had been admitted before they were five years of age.

In several schools in manufacturing Urban Districts all the children had been admitted before they were five years of age.

In nearly all the schools I visited the teachers were of one opinion, namely, that the parents find the Infant Schools a convenient means of getting their offspring out of the way. In one case, a parent's description of a "Free School" was "a school to which I can send my child when I choose, and keep it away when I choose".

Class of children admitted under 5 years. The poverty of parents who have only one room, sometimes no fire, and often younger children to attend to, is a factor in the case. When the elder girls are at school there is no one to look after the young ones. In manufacturing towns, many of the mothers work at factories, and must, consequently, get rid of their babies. In these districts, they would have to pay as much as 2s. 6d. or 3s. 6d. per week, without food, for having their little ones minded. It is natural that they should avail themselves of the free shelter, protection and care which is provided in the babies' classes. A few send them with a desire for the child's educational welfare, but these are the minority.

The teachers also, exert their influence to gather them in. "Since they are registered, and accommodation provided, they

[page 143]

might as well be here", they say. Practically, therefore, all those of the poorer class are sent at three or four years.

Numbers also, play so large a part in Education Reports that the success of a teacher is partly dependent on her power of filling her school, and the keeping up or increasing the average attendance.

Lastly, the Attendance Officer plays no small role in persuading mothers to part with their little ones earlier than they otherwise would. According to the law, the officer has no hold on children under five years of age, but he is judged by his returns, and the higher his percentage of average attendance is the better officer is he considered and the attendance of children under five years of age is included in his returns.

The small minority who enter at five or six years include:

(1.) Those prevented by serious illness or by physical or mental defect from coming earlier.

(2.) Children of good homes and well-to-do parents, who are able and willing to look after them in infancy and do not care to lose sight of them for so long. But such parents are few.

(3.) Children in a poor neighbourhood with intemperate or utterly indifferent parents, who will let them roam the streets until hunted into school by attendance officers.

In a large girls' school in a working class district, out of 324 girls present, fifty-three had been sent at five years of age. Their parents were asked why they had not sent their children earlier. It turned out thirty-seven were not sent because they were delicate or had had a severe illness, only twelve because they were not obliged to send earlier, and three because they lived in the country, two or three miles from a school, and one lived in the United States.

In the boys' school out of 360 present, 293 started under five years of age and sixty-seven at five years of age: forty-three because of serious illness or delicacy, twenty-two because not compelled, and two because they lived in the country at a distance from any school. In these same schools forty-six mothers went out to work in the boys' school, and fifty-six in the girls' school.

In a girls' school in a very poor neighbourhood of _______, out of 246 children present, fifty-one started at five years of age and two at seven years: twenty-two because of serious illness; nineteen because not obliged; six through neglect and drunken homes; two because of distance, and one came from the United States. On inquiry, fifty-six mothers went out to work.

Progress made before five years. Those children who enter at three years may be said to make a certain progress in mastering some of the mechanical difficulties of reading, writing, and arithmetic. They also gain some power of order, attention to rule and discipline, and a certain capability of expressing stereotyped ideas. But I consider there is very little real educational result. In each successive year they practically go through the whole course of instruction again. Their minds, being too immature to

[page 144]

retain easily the knowledge acquired, there is entailed a wearisome repetition, which must have a stultifying effect on the young brain. Thus at the expense of much real hard labour, they succeed in exhibiting a certain amount of mechanical skill, which, however, children of five, with more mature powers, will acquire with less trouble in a much shorter period. Worst of all, they lose in the process whatever originality they may have started with, and take the first step towards being turned out "patterns" of the approved type.

Comparison with others of 6 or 7. Comparing this class of children with those admitted at five years of age, at the termination of the infants' course, there is little difference to be observed. On admission to the school, the latter may appear, for a few weeks, less orderly than their class-mates, owing to their ignorance of rules and the effect of strange surroundings. But after a short time they pick up much by imitation, and soon settle down into the usual school ways.

Again, in the earlier stages of work, they appear at a disadvantage through want of fluency in reading, number, etc., but they are in reality quicker than the others, as they get through the whole previous syllabus of work in less time.

If they enter at the beginning of the school year they are found to be practically equal to the others at the end of one year.

Powers of observation and originality of ideas differ so extremely by reason of the character and home training of a child, that it is difficult to make a comparison between these two classes of children in these respects. There is scarcely any difference to be observed with average children. If anything, the balance of originality lies with the child admitted later, who has not had so much of the levelling process of "pattern-making" applied to him. School work, as at present carried on, does not tend to develop originality; rather is it crushed before that "Car of Juggernaut" - Uniformity.

In powers of expression the earlier child has gained the confidence that comes with custom, but is often priggish and unnatural, while the later child is more homely, though less fluent. The latter uses its own words; the former, those of its teacher.

These differences are more marked in poor neighbourhoods, where the parent's influence is nil, or worse, and the child gets no assistance outside the school except such as is the outgrowth of its own ability.

By inquiries made with head teachers of senior schools, who have followed up the separate classes through their school career with a view to comparison, the final conclusion must be reached, that average children make as much progress by late as by early admission. Disparity is caused by ill-health, home environment, etc., not by later attendance.

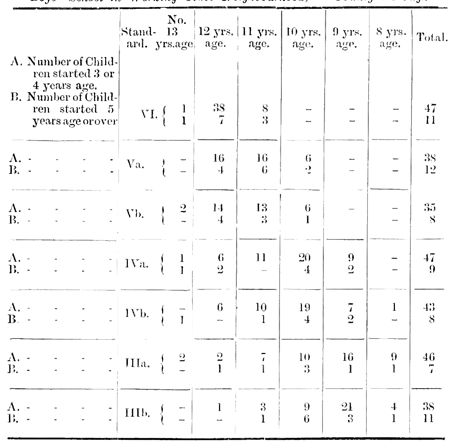

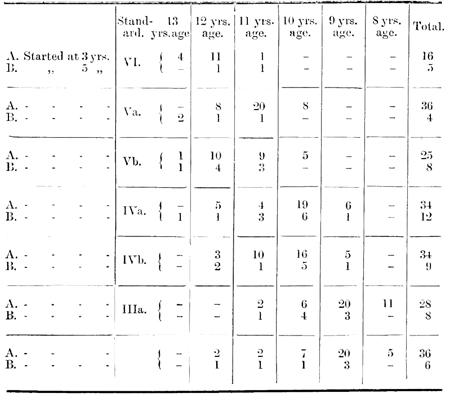

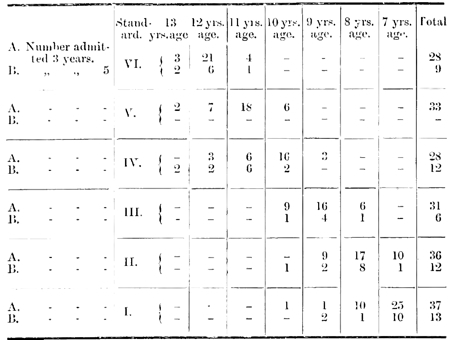

The following tables may help to show that children admitted at five years of age compare favourably with other children, age for age.

[page 145]

Boys' School in Working Class Neighbourhood - County Borough

Girls' School in Working Class Neighbourhood - County Borough

Girls' School in Working Class Neighbourhood - County Borough

[page 146]

Girls' School in Poor Neighbourhood - County Borough

In many cases, these children are the best in their class. It must not be forgotten, however, that in a poor neighbourhood children often gain, physically and morally, by entering the school at three years of age, since they are better cared for, and removed from the bad influence of intemperate or neglectful parents.

Times of Admission of Infants. It is most detrimental to the interests of the school, the teacher, and the child, that the latter should be admitted at all times of the year. Teachers say it is one of their chief difficulties that children are allowed to dribble into the Infant School in twos or threes every week in the year while there is accommodation. Such children are not fit to follow any class and yet no school can provide a teacher for them alone. The best arrangement would be to admit only at the beginning of the school year; but if this is not practicable, admission every six months is quite sufficient.

If every six months, then a practice which has been satisfactorily tried by the _______ Council schools might be put into use, i.e., the passing up of infants into the upper departments twice a year. This would enable children who now are deprived of six or nine months infant training, owing to the time of year in which their birthday falls, to have their full time in the Infant School. As a rule, all children should be regarded as infants until they have at least completed their seventh year. In _______shire schools, it seems the rule that children who will be seven years of age before the end of the following school year, that is, turned six years of age at the end of the present school year, must be promoted to the upper departments. It is thus quite common to find children doing Standard I work at six years of age,

147]

Registering under 4 years. I incline to the opinion that children under four, if they continue to be admitted to our schools, should remain unregistered. As long as they are registered and available for grant the teacher, whose character as a popular and successful member of the profession depends upon her percentage of attendance, must try to get them into school, morning and afternoon, and in this way, babies are often in school when unfit and even sickening for diseases. If admitted only, they could be left free to attend one session, which is often enough to exhaust their delicate frames and unformed brains. Children of such tender years require a daily hour or two of sleep, and how can this be obtained under present conditions?

Physical Condition. It is evident that insufficient attention is paid to the general physical condition of infants. The children are so often cooped up in galleries, sometimes for one and a half hours or more; too often crowded and without proper back rests. In more than one school, if one in the row moved, those at the end fell off.

Despite all that has been said and done of late years in the study and increase of Physical Exercises, drill is still, in many places, a mere name on the Time Table. Or it is taken in desks or seats. Exercises at change of lessons are reduced to mere arm movements, and the little legs have to keep as still as they will for sometimes a whole session. I have been in schools where there is absolutely no playtime in winter. The children, being marched out, stand on a chalk line until recreation time is up and the teacher ready with her apparatus, v/hen they march back again with their hands behind.

The position 'arms folded in front' which is so hurtful by compression of the chest, is continually called for. I have even seen it taken at singing lessons.

In schools of the _______shire district which I have visited there are no periodical visits of trained nurses as in the London schools, and the children are present in the first stages of infectious disease, which often pass unnoticed by the teacher of over-crowded classes. It is no wonder that epidemics spread so rapidly in a class when once started.

Health Records. In no infant schools visited are even the simplest health records kept. There should be for the sake of teacher and taught, a medical inspection of all children, infants as well as older scholars, and records kept of the physical condition of every scholar. These records could be posted to the different authorities when children leave one district for another. Mental, as well as physical injuries and diseases might thus be remedied or even prevented, and children unfit for school work would not be pushed, as is now so often the case, to the detriment of both mind and body in after years. At present, what little medical inspection there is, is usually confined to the upper departments, though it is in the Infant school that the seeds of ill health are sown.

[page 148]

Eyesight. Statistics as to eyesight, where taken, are only taken in Upper Schools. In the _______ Council schools, absolutely no notice is taken of defective sight, and the teachers say it is no use to test, for nothing further is done. They do their best by calling the attention of the parent, but these will not take their children to the Infirmary, or say they cannot afford to pay for glasses. Children with weak sight and inflamed eyes attend school, and do the same work as others.

The following may be interesting. In a boys' school, out of thirty cases of defective sight, twenty-six cases were children who started school at two or four years of age. Only four were children who started at five years of age, and out of these, one was the result of an accident, i.e., stone-throwing. In another school, out of twenty-five cases, twenty-two were children who started at three or four; three were those who started later.

Again, out of fifteen cases in a girls' school, twelve were children who started at three years, three at five years, and two of these were not sent till five because of delicate eyes. In another school, out of forty-nine cases of defective sight, forty-four were children who started at three years; five started at five; and three of these were not sent till then owing to defective sight.

The children's eyes suffer in early school life, by the school work. The light is frequently from the right. Children of three and four years are required to thread needles, and where slates are still used, to write between lines, which are often half-erased and can hardly be seen. In twenty-three schools I visited, I found the babies writing on slates between lines.

Movement, Play and Rest. Movement, play, and rest receive but a very moderate share of attention in the daily round of duties. In one school a swing is used - sometimes on Friday afternoons. In another, a rocking-horse is for the comfort of 'children who cry'. A _______ teacher said "The first thing we teach them is to sit still. It has always been required of us".

Comparing a time table of one of the German "Volks-kindergarten" which lies before me with those in use in our infant schools, the contrast is striking. Thus the Kindergarten provides daily:

| Morning | Afternoon |

| Intervals | ½ hour | ¾ hour. |

| Story telling | - | ½ hour |

| Active amusements | 1 hour | 1½ hours. |

The rest of the teaching is made up of object lessons and Kindergarten occupations and games. Reading, writing, and number are unknown lessons.

In English schools we have a quarter of an hour interval, morning and afternoon. In twenty-four schools visited, only one and a half hours per week are devoted to object lessons and conversation. As for reading, nine schools had either four and a half hours or over devoted to this subject; fourteen had from three and a half to four and a half hours; twenty-one had from three to three and

[page 149]

a half hours; twenty-six had two to three hours. Number, too, eats up a large share of the Time Tables. Five schools had four and a half hours or more. In writing, eight had three and a half, and twenty-nine had from two to three hours. Stories, which in the German schools get half an hour a day, only receive half an hour a week in our schools. Needlework is still taught to the babies; on nineteen Time Tables it still held a place.

The rest between lessons, so often appearing as a note to Time Table, is omitted in many schools, as the teachers " cannot spare the time " with all the work to be got through. A mattress bed is sometimes provided for the babies but not much used. Half a dozen hammocks, round the walls, would be cleaner and more convenient. But the child, for the most part, falls asleep unnoticed, and is left at the desk for fear of waking it.

Physical Condition and Mental Proficiency. Mental proficiency and physical conditions do not seem to go hand in hand. In five cases out of six, delicate children are quick-brained. Often the very healthy, well-built child is by no means sharp - if anything, rather dull. Possibly bodily deficiency makes the child more thoughtful and studious.

Teaching of ''three R's". I wish most emphatically to protest against the teaching of the "three R.'s" and needlework to children under five or even six years. In the course of nature, speech comes before reading and writing, and the child of three or four has not yet learned to speak. Its vocabulary is so limited that the simplest words are often meaningless to it. They are only empty sounds, and it therefore becomes a human gramophone for the production of the teacher's voice.

Also, at this immature stage of development, the child has not the mental capacity to understand or to retain the arbitrary facts connected with the sounds and signs of which the first steps in reading and writing are mainly composed. Often, if an illness interrupts the course of lessons in these years, the child is found to have lost all it had previously learned. In fact, nothing is gained but a slight mechanical power, whose painful and laborious acquirement is calculated to give a distaste for the sight of books before they are opened. Two years later, when the memory is stronger, and the general capacity increased, less effort is required and impressions remain permanent.

As regards needlework and writing, the strain on the muscles of hand and eye involved in the attempt to hold needle and material in right position for a fixed time, is too great. The results are quite inadequate to the labour. At six years the child learns in a few lessons what is, to the baby, a Herculean task. The tiny hand is still an imperfect, unformed tool, yet the attempt is made to produce work which requires a perfect tool. It is like cutting wood with a blunt knife. Expend the same amount of energy on possibilities, and there will be some happier children and teachers.

Methods of Teaching. Before pointing out what I consider the

[page 150]

chief defects in methods of teaching infants, let it be understood that I am not finding fault with the teachers. Almost universally, it may be stated, they have the true welfare of their charges at heart and the methods they adopt are often not their own choice but forced on them by the exactions of Code, Syllabus, and inspectors, or deficiencies in the school building.

So long as "Results" are looked for in infant schools, even from babies, so long must the teachers continue to work along the lines which will produce results. The true development of the child is slow, for Nature does not seek to force a blossom from the seed still in embryo. It is by "Methods" alone that infant schools should be tested. If these are truly educational satisfactory results must follow, but they will not be evidenced by ability to read certain words correctly, to add or subtract so and so, or to copy out beautifully. It is the amount of desire to acquire knowledge, and the power to use its faculties in acquiring it, in other words, the power of self-instruction that mark the success or non-success of the product of the infant school. Individual development and formation of character, should be the highest aims of infant teaching.

Yet "Results" [definite, uniform proficiency in the "three R.'s"] are still called for by Board of Education and Council Inspectors, therefore "Results" are still the "Ideal". To pass Standard I. with credit is the goal for which the child is entered in the race, at three years. Naturally the teachers try to please inspectors and to get certain things done to make a show. A Council Inspector remarked in a certain school that "the discipline would have been perfect but for two or three babies who moved". It is easy to understand how, thenceforward, the unfortunate babies "sat up". In this district, also, the Syllabus imposed by the Council is cast iron. Every week is mapped out in rigid lines, so much in each subject to be got through and shown. In one school, an assistant teacher, though admittedly one of the best on the staff, was deprived of her increase of salary because her class was not quite up to the mark in providing the appointed facts and figures.

But to bring a large class of young children up to this state of uniformity of excellence, it is impossible to do anything but work on set lines of drudgery. Consequently, the discipline is too severe, free movements are repressed, the teacher does much (with misdirected energy), while the scholars sit, passively waiting to be told to do something. All individuality is crushed; they must all work to pattern and be like everybody else.

The classes are much too large, as many as sixty or even eighty babies being often in charge of one teacher. Kindergarten games are too mechanical, because noise or movement is contrary to the recognised idea of discipline. In many cases these games are reduced to the quality of action songs. The majority of school buildings, however, make no proper provision for such exercises which require considerable space and whose value depends on their spontaneity.

[page 151]

Occupation lessons are often distinguished by their absence of occupation, for the children have to sit motionless while the teacher goes round a large class and examines the infinitesimal product - the one letter or figure made - the one thread drawn - the one bead threaded, or the one stick laid. Meanwhile, there is a whole world of wonder to be explored on the desk before the child, from which its longing hands are barred by "discipline". This is not "learning by doing".

Universally, the standing principle seems to be that mistakes must never be made. Perfection is expected at a first or second trial so that fatal discouragement enters the baby soul that ought never to have come near it, and the joy of finding out for itself and climbing by its own mistakes is never known.

With the object of avoiding the excessive crowding and the cramping of limbs caused by the use of galleries, I would advise their rejection, especially in babies' rooms.

The ideal babies' room should be large, sunny, without gallery or desks, but supplied at one end with small kindergarten tables and chairs, round which the little ones can sit without disturbing each other by every little instinctive motion. The teacher can pass round and overlook them easily.

A wide space should thus be left at the other end of the room for games. In addition, a large comfortable rug should be stretched before the fire for the youngest to lie or crawl about, with perfect freedom, or find comfort when brought in from the cold. Round the walls should be placed a blackboard cloth dado, and plenty of coloured chalks supplied that the children may draw "fancy free" with the teacher helping - never teaching. A much larger supply of toys is needed, that each child may have one to handle. In better neighbourhoods, the children might be encouraged to bring their own toys. Pictures and plants should abound, and birds and other pets, to give the interest in life which is so helpful to the intelligence and powers of observation.

Offices. Offices [toilets] are not sufficiently numerous for the babies, and boys and girls should have separate entrances. Some few might be nearer their class-room, and with a covered passage for use in wet weather.

Medical Work, etc., in Schools

In one County Borough the medical officer of the Education Committee visits every school at least twice a year for the purpose of testing both the sight and hearing of the children in attendance. In some schools the teeth of children in Standards VI. and VII. were also examined.

Vision. Every head teacher must, according to the Education Committee's regulations, test the eyesight once a year of:

(1.) All new scholars admitted during the year.

(2.) All scholars in Standards VI. and VII.

[page 152]

A vision card is filled in for each scholar examined, giving the following details:

Vision of right eye.

Vision of left eye.

(1.) If the child wears glasses or squints?

(2.) If the eyelids are often inflamed?

(3.) If there is complaint of frequent headache or fatigue of the eyes after reading or sewing?

The doctor at his visit re-examines all cases below a certain mark, and in cases requiring medical treatment and capable of improvement a printed notice is sent to the parents advising them to consult a medical man either privately or at the infirmary. A footnote is added drawing attention to the fact that medical advice may be had free at the Royal Infirmary on Mondays and Fridays at 1.30 p.m. and at the Eye and Ear Hospital on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 9.30 a.m. Except in very needy cases spectacles are not provided free of charge.

The teacher's interest in many cases seems to stop once the printed notice has been sent out. In no school did I find a list of children suffering from defective vision. A list of these children with an entry of date when medically treated, or reason why medical advice was not sought, would be a great help in keeping these cases under observation. New teachers are left to find these cases out for themselves. I found children who had been attended to and had glasses not wearing them. In some cases the teacher in charge of the class did not know that certain children had glasses. Some cases had not been attended to because the mother was the bread winner and could not spare a day to take her child to the hospital.

It seems to me that half of the doctor's trouble is lost if these cases of defective sight are not kept under observation and in cases when notices are neglected the matter is not followed up. Unfortunately many of the teachers take little interest in work not reported on by H.M. Inspector, particularly if it entails an increase of clerical work.

In another County Borough the sight of all children in the upper schools is tested once a year by the head teacher. All defective cases are re-tested by the medical officer of the Education Committee and a printed notice is sent to parents drawing their attention to any defects of vision and requesting them to have their children's eyes examined by a doctor. With the sending out of the printed forms the interest of the head teacher stops.

Again in another County Borough each school is provided with a sight-testing chart, but in no school visited was the sight of the scholars tested periodically.

In one County Borough, about two years ago, all teachers were requested to test the sight of the scholars in their school and report to the late board the number of cases of defective sight in their schools. Beyond this no interest appears to have been taken either in the sight or general health of the scholars.

[page 153]

In schools under the _______ County Council visited I found the teachers had been supplied with a printed form to draw the attention of parents to cases of defective sight.

Further experience gained by visits to village infant schools and classes during the last few weeks only serves to confirm the impressions recorded in my previous report.

Age of Admission. Here, as in towns, the majority of children enter school under five years of age - usually at four years, but in manufacturing villages at three years. The attendance officers say the teachers encourage their admission, so, with the child crying to go, the mother glad to be rid of it, and the teacher welcoming it in, the inevitable result is to fill the babies' room.

Progress. I can still observe no loss sustained by admission at the later age of five. Age for age the two classes of early and late admission may he favourably compared. Ten out of thirteen teachers concur with this opinion. Out of 268 children traced from late admission only twenty-eight, about 10 per cent, were below average as being above the age of the class they worked with. Of the 90 per cent remaining many were not only on an equality but the sharpest in their class.

Hygienic Conditions. The conditions of instruction and accommodation in many village infant schools are anything but satisfactory. In schools with an average attendance under fifty the infants are mostly taught by one teacher in a room often badly lighted and ventilated. Since these scholars generally include at least two classes, the babies^ dribbling in by ones and twos all the year, improve the shining hours (twenty hours per week) by scribbling on a slate. They must be satisfied with an odd five minutes here and there which the harassed teacher can spare from the higher class. On many time tables, where neither games nor stories are to be seen, needle-threading, a refined species of torture, often continues for twenty minutes or half an hour. Writing in sand is gradually being introduced, but slates with lines are still too much used. There are usually two teachers where the average attendance is over fifty, and here the babies go with the second class and fare in like manner. When the number of babies reaches twenty, they attain to the dignity of having the entire attention of a monitress or pupil teacher and afford an excellent practising ground for her inexperience. The benefit on their side is doubtful. Under these circumstances it would be wiser in a country district if children under five years of age could be legally refused admission and those over five years entered at regulated times, say twice a year. Many of the difficulties of teaching in small schools would be removed, and the child's freedom would be a physical and mental advantage to all concerned.

Chief Defects in Teaching in Infant Schools

As before observed the aim of the Infant School from the babies upwards is preparation for inspection in Standard I. Conse-

[page 154]

quently the three R.'s receive the lion's share of time and attention, and more important subjects must take their chance. A pupil well advanced in these great dogmas of a teacher's faith is a shining light, but how far it is capable of receiving further instruction is a question of no importance.

Syllabuses of work require far too much from these little children. The following is a copy of a not uncommon syllabus in number for a first class infants - average age at the end of the school year six and a half years:

Tables to five times twelve.

Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division to 100.

Notation to 1,000.

Names and value of coins to £1. Money problems to 2s. 6d. Value of easy fractional quantities, e.g., ½, 1/3, ¼.

Discipline. Discipline is invariably interpreted to mean: "Sit up - sit still - fold arms back (or front) - eyes front". To be eager and alert, and want to answer "out of turn" is "to be naughty". I plead for the recognition and toleration of a healthy noise in the lower classes of our infant schools. The want of large airy playrooms, free of furniture, that the little ones may enjoy a good romp and play under proper supervision is much in evidence. Formal physical exercises as taken in many schools are unnecessary at this early stage of life. Free play, however, for periods of half an hour at a time is a necessity of physical development. In connection with this I may remark on the rooted objection possessed by many bead teachers to the use of the hall by the babies - lest they "distract the other classes". Even in wet weather these sacred precincts must not be defiled by the noise and laughter of little ones. The hall is a place round which each class marches for five minutes, and for the rest of the session it is unpeopled as an African desert.

Hours of Work. The hours 9 to 12 a.m., and 1.30 to 4 p.m., are far too long. Children of five and six years of age have been punished for not being present at 9.10 a.m., though the registers close at 9.30 or 9.45. The parents are not in many cases aware of the fact that infants need not be in school before this time, and so many go breakfastless for fear of being late. Yet this lateness is often the result of circumstances, due to large amount of work to be done in a big family in the early hours where the mother is frequently unaided. Parents might be encouraged to send their children only to one session of the school - either morning or afternoon.

Size of Classes. Classes are everywhere too big. How can one teacher "mother" sixty to eighty children, and keep them occupied and quiet, often under such adverse conditions as unsuitability of furniture, insufficient fight and ventilation, and overcrowding on a hot summer's day? Yet this is a problem which she has often to solve.

In the playgrounds there is a general want of seating accommodation.

[page 155]

Offices [toilets] are often insufficient in number, dark and unsanitary in arrangement, and totally unsuitable for teaching habits of decency and cleanliness.

Lastly, the gap existing between the infant department and the upper departments is considerable, and much of the training of the infant school is lost.

The work of Standard I. should be carefully co-ordinated with that of the infant school that there may be no break when the child is moved from one department to another. If teachers of the lower standards were made familiar with Froebelian principles and had a working knowledge of Kindergarten methods, much hardship and many weary hours would be spared both teachers and taught.

AGNES F. HARRINGTON.